You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Real life’ category.

Do your diabetes appointments take on an eerily familiar routine? When I was first diagnosed, each appointment would open with the words ‘Let me see your book’. My endo was referring to my BGL record, an oblong-shaped book that I was meant to diligently record my minimum of four daily BGL checks, what I ate, what I thought, who I’d prayed to, what TV shows I’d watched and how much I exercised.

I did that for about the first two and a half months, I mean weeks, okay, days and after that the novelty wore off and I stopped.

I’m not ashamed to admit that I did that thing that pretty much every single person with diabetes does at one point or another – I made up stuff. I was especially creative, making sure I used different coloured pens and splotched coffee stains across some of the pages here and there, little blood speckles for proof of bleeding fingers, and, for a particularly authentic take, OJ, to reflect the made-up numbers that suggested I’d been having a few lows.

I’d show those creative as fuck pages – honestly, they were works of art – when requested, roll my sleeve up for a BP cuff to be attached, and step on the scales for my weight to be scrutinised. Simply because I was told that was what these appointments should look like, and I knew no better.

And then, I’d walk out of those appointments either frustrated, because I’d not talked about anything important to me; in tears, because I’d been told off because my A1c was out of range; furious, because I hated diabetes and simply wasn’t getting a chance to say that. And anxious, because looking at the number of kilograms I weighed has always made me feel anxious.

The numbers in my book, on the BP machine or the scales meant nothing to me in terms of what was important in my diabetes life. They stressed me out, they made me feel sad and hopeless, and they reduced me to a bunch of metrics that did not in any way reflect the troubles I was having just trying to do diabetes.

These days, not a single data point is shared or collected unless I say so. I choose when to get my A1c done; I choose when to share CGM data; I choose to get my BP done, something I choose to do at every appointment.

I choose to not step on the scales.

I don’t know what I weigh. I might have a general idea, but it’s an estimation. I don’t weigh myself at home, and I don’t weigh myself at the doctor’s office. I think the last time I stepped on a set of scales was in January 2014 before I had cataract surgery and that was because the anaesthetist explained that it was needed to ensure the correct dose of sleepy drugs were given so I wouldn’t wake up mid scalpel in my eye. Excellent motivator, Dr Sleep, excellent motivator.

Last month, I tweeted that PWD do not need to step on the scales at diabetes appointments unless they want to, and that it was okay to ask for why they were being asked to do so.

There were comments about how refusing to be weighed (or refusing anything, for that matter) can be interpreted. I’ve seen that happen. Language matters, and there are labels attributed to people who don’t simply follow the instructions of their HCP. We could get called non-compliant for not compliantly stepping on the scales and compliantly being weighed and then compliantly dealing with the response from our healthcare professional and compliantly engaging in a discussion about it. Or it can be documented as ‘refusal to participate’ which makes us sound wilfully recalcitrant and disobedient. It’s what you’d expect to see on a school report card next to a student who doesn’t want to sing during choir practise or participate in groups sports.

What surprised me (although perhaps it shouldn’t) was the number of people who replied to that tweet saying they didn’t realise they could say no. it seems that we have a long way to go before we truly find ourselves enjoying real person-centred care.

Being weighed comes with concerns for a lot of people, and people with diabetes often have layers of extra concerns thanks to the intermingling of diabetes and weight. Disordered eating behaviours and eating disorders are more common in people with diabetes. Weight is one of those things that determines just how ‘good’ we are being. For many of us, weight is inextricably linked with every single part of our diabetes existence. My story is that of many – I lost weight before diagnosis and people commented on it favourably, even though I was a healthy weight beforehand. This reinforced that reduced weight = good girl, and that was my introduction to living with diabetes.

From there, it’s the reality of diabetes: insulin can, for some, mean weight gain, high glucose levels often result in weight loss, changes to therapy and different drugs affect our weight – it’s no wonder that many, many of us have very fraught feelings when it comes to weight and the condition we live with. Stepping on the scales brings that to the fore every three months (or however frequently we have a diabetes healthcare appointment).

Is it always necessary, or is it more of a routine thing that has just become part and parcel of diabetes care? And are people routinely given the option to opt out, or is there the assumption that we’ll happily (compliantly!) jump on the scales and just deal with whatever we see on the read out and the ensuing conversation? And if we say no, will that be respected – and accepted – without question? Perhaps another positive outcome is that it could encourage dialogue about why we feel that way and start and exploration if there is something that can be done?

It shouldn’t be seen as an act of defiance to say no, especially when what we are saying no to comes with a whole host of different emotions – some of them quite negative. Actually, it doesn’t matter if there are negative connotations or not. We should not be forced to do something as part of our diabetes care that does not make sense to us or meet our needs. When we talk about centring us in our care, surely that means we decide, without fearing the response from our HCPs, what we want to do. Having a checklist of things we are expected to do is not centring us or providing us the way forward to get what we want.

How do we go about making that happen?

There are two boxes on my desk today because I am recording a little video for a new series at work. In my diabetes store cupboard, there are lots of boxes from currently using and past diabetes devices and products.

These boxes all contain promises and hope – promises to make diabetes easier and the hope that some of the significant time dedicated to something that no one really wants to dedicate time to is gained back.

Burden is very personal. One person’s significant diabetes burden is another’s mild inconvenience. Some look at a CGM and see life changing and lifesaving technology and others see a nagging device of torture. I vacillate between the two trains of thought.

No diabetes device is perfect and does all things. Most rarely even do what they promise on the box.

And yet when we look online often all we see is the perfect stuff. With diabetes tech companies getting smart and becoming all social media savvy, they have looked to the community to see how we communicate and share. It’s not a silly thing to do. Many of the decisions I’ve made about diabetes tech choices have been based on what my peers have to say. But I’m selective about who I search for when looking for those personal experiences and testimonials. I look either for people I kind of know, or people who have a history of being open and honest and real about their experience.

I’d make a lousy ambassador, even though I am asked almost daily to either become an ambassador for a company or promote their product, with lots of free stuff thrown in. Some offer payments. Sometimes I agree to try something, but there are never any strings attached, and while I will accept the product, I will never be paid for using it, or for writing about it. (You can see that in my disclaimers when talking about product. I always say that I’m sharing because I want, not because it’s part of the arrangement for me to use gifted or discounted product. I’ve never done that.) That’s not to say that I have not had arrangements with different companies and been paid an honorarium for my time and expertise, but that is always in the capacity of being an advisor, or consultant.

I’m too honest about the challenges of different diabetes technologies – you bet I love Dtech, but not everything about all of it! It’s why I am always wary of anyone spruiking any diabetes product who has only positive things to say. In the last 20 years, I’ve used or tried pumps from Medtronic, Cozmo, Animas, Roche and Ypsomed. I have loved them all. And hated them all. I’ve never had only good things to say about any of them – even the Cozmo which remains my favourite ever pump, and anytime I see one, I have strong happy feelings of nostalgia…but despite that, it still had its failings that I spoke about often when I used it.

I’ve used CGM products from Medtronic, Dexcom and Libre and had few good things to say about some generations, better things to say about others, but never loved every single aspect of any of them. Because there is always something that isn’t perfect, or even almost perfect.

And finally, I’ve used countless blood glucose monitors from every brand in Australia and some I’ve picked up on travels, and it’s the same deal: love some things, drop the f bomb about others.

The times I have been gifted products, I have always been honest when talking about them, highlighting the pros and cons. Even though I always write about the positives and negatives, I’ve always urged people to read or listen to whatever I have to say understanding that there is a lens of bias with which I see them through. Of course there is, and others should consider that. I also know I have never consented to having anything I’ve said or written reviewed or amended by the company who has kindly gifted product, or have I promised to do a certain number of posts or tweets or Insta pics about them. The sharing I do is always on my terms as are the words in those shares.

I have, however seen many contracts these days that are very prescriptive when it comes to the expectations and commitments of the people being given product. I don’t have an issue with that; I couldn’t care less really. But I don’t think that simply putting the words #Ad on a post gives people the true picture behind the arrangement in place, which is important for the reader if they are to consider just what bias could be at play when reading someone’s opinions.

I am always pleased when I see that industry is engaging with PWD. There should be clear lines of communication, and hearing what PWD say is critical – far more so, in my mind, than what the shiny brochures have to say. But just as I read what the company’s PR messaging has to say with some scepticism, I do the same when I am not clear of the pact between the company and the PWD.

Diabetes devices rarely, in fact, I’d go so far as to say NEVER, do all that they promise on the box. I think I’ve known that all along, but it wasn’t until I started using something that doesn’t come boxed up in sparkly, fancy packaging that I truly realised just how much that wasn’t true.

Those promises to do less diabetes – to reduce that burden – was only ever true to a small degree. And sometimes, there was added burden that you could only truly learn about if you knew where and how to access others with diabetes, in particular those that didn’t sound as though they were simply regurgitating what the brochures said.

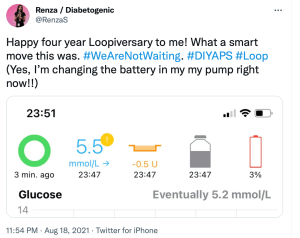

Using an out of the box diabetes tech solution isn’t all perfect. There are somethings about DIYAPS that annoy me. A red loop on my Loop app can be frustrating – even if it’s a simple fix. Needing to carry around an OrangeLink and making sure it’s in range gets irritating. Not having a dedicated 1800 number that I can call 24/7 and handing over any concerns to someone else means that the troubleshooting burden falls squarely on my shoulders – even if there is a community out there to help me through.

And yet, even with all that, it is the first time ever that I have been able to say that I do less diabetes. How much less? Well, I think that Justin Walker’s assessment from a presentation at Diabetes Mine’s DData event back in 2018 is right. He said that using a DIYAPS has given him back an hour a day where he no longer needs to think about diabetes.

Last week, I hit four years of Looping. That’s 1,460 hours I’ve clawed back. Or over 60 days. If DIYAPS came in a box (and with a PR machine and marketing materials) and it promised me that, I wouldn’t believe it based on previous experience. But I guess that’s the thing. There is no box, there is no marketing juggernaut. It’s just the stories of people with diabetes who have worked through this and worked it out for themselves.

An out of the box marketing solution for an out of the box diabetes technology solution. I’ve never trusted anything more.

Friends, how’s your mental health today. Mine. Is. Shit.

Gosh, I feel as though I have been through the wringer, hung out to dry and then, just at the moment that everything was looking good again, dropped in a muddy puddle and trampled on by a herd of bison. I mean, not really, because bison are not typically found in the especially hipster part of downtown Melbourne I reside, but hopefully you now have a picture of how I’m feeling.

Not even the overabundance of sparkly necklaces (and ever-present red lipstick) I threw on this morning can distract from the fact that I am exhausted, look as though I’ve been weepy for most of the day (because I have) and am just feeling so damn over everything right now.

Somehow, I held it together for a live Q&A about diabetes and mental health which I may or may not have treated as my own personal therapy session. (You can watch the video here.) Thankfully, psychologist, the ever-wonderful Dr Adriana Ventura, offered some fabulous tips for how to take care of our mental health during this time that is still being referred to as unprecedented times, but I’ve taken to calling the clusterfuck period.

The moment today that was the most difficult for me to deal with was just after 11am when the NSW Premier told us the grim news out of her state. I know that I probably should stop watching the pressers, especially the ones out of NSW. It’s not my state, so most of what is being said is actually not all that relevant to me and my family, and the repeated lies that are casually thrown around like confetti at weddings we can’t have anymore make me furious. And yet, even knowing that, I find myself sitting through them most days, yelling at the screen while madly tweeting my fury.

But today, instead of yelling, there was crying. The NSW Premier said ‘We extend our condolences to the family of a man who has died. He had received one vaccination. And he DID have underlying health conditions.’ She accentuated the word ‘did’ to underline what she was saying.

And so, where back, or perhaps still, at this point. That point is where we dismiss those with health conditions as nothing more than covid collateral.

I cried as she said it, angrily wiping away tears at how easily I was once again being made to feel expendable. I felt sad and broken and just so damn beaten. I have spent the last twenty months doing all I can to protect myself, knowing full well that those efforts protect others too. I rarely go out; I never leave the house without a mask; I’ve washed my hands and rubbed so much sanitiser into my skin that I feel the dermatitis that has started will never leave; I’ve followed all restrictions; when I do go anywhere, I check in at each location; I’ve had a covid test every time I so much as feel sniffly; and I got vaccinated the second I was eligible.

I have been deliberately compliant when it comes to covid.

And when it comes to diabetes, my deliberate non-compliance has meant that I am continuing to manage in a way that, according to every HCP and researcher I’ve ever met, is giving me the best chance to live well and to live long with diabetes.

And yet, despite all that, if I get covid and die, the message is it’s because I had an underlying condition. I already have one foot in the grave; covid just gave me a gentle push the rest of the way.

Well, fuck that.

I know I’ve written about this before, and honestly, this far into it all, I should be better at just ignoring it. But when it is coming from our politicians and the media, and I’m hearing it from people in the community, it’s hard to not take it personally.

The man the NSW Premier referred to, died from covid, not his pre-existing health condition. It certainly may have meant that covid was complicated for him, but if he’d not got covid in the first place, he probably would still be alive. His underlying medical condition doesn’t make him any less worthy, or any less of a loss. It doesn’t excuse his death.

I don’t know when people will stop with this hurtful and harmful rhetoric. I’d have hoped that by now the communication efforts from those who stand up every day to tell us the bad covid news would be more nuanced and more respectful.

I guess that’s too much to hope for.

Often when we talk or read about technology it is very much about the latest, newest, shiniest devices. And yes, I wrote about those last week. There’s nothing wrong with learning about latest tech releases, or desperately wanting to get your hands on them.

But the devices are only ever half the story. And that’s why it was so great to see that in amongst all the data and the new things, was a presentation that reminded everyone watching the technology symposium at ADC that the data belongs to people and the devices are worn on the bodies of those people.

This is the whole warm hands, cool tech concept that is often missing when we hear about technology. The devices are not inanimate, they need human interaction to make them work for … well … for humans.

I despair at some of the stories we hear about technology and people with diabetes. Some talk experiences that have left them feeling like a failure when the tech has simply not been right for them. Because that is the way it is posed. If we decide the tech doesn’t suit us, hasn’t worked for us, hasn’t helped us achieve our goals, we’ve failed it.

The truth is, it’s more likely that the failure – if we need to frame it that way – is not the PWD at all. It’s more likely that the tech is not right for the person, and there wasn’t enough assistance to help navigate through to choose the right tech. Or the education was insufficient, or not tailored for the PWD, or not interesting, or not relevant (more on that soon, from Dr Bill Polonsky’s opening plenary from the conference). It is possible that the timing wasn’t right, the circumstances were not optimal, not enough conversations about cost or effort required … whatever it is, none of the blame for something not being right should be placed on the PWD.

When we look at diabetes education, or engagement with healthcare professionals, the stories that are celebrations or considered successes (from the perspective of the PWD and, hopefully, the HCP) show the right recipe. The ingredients will all be different, but the method seems to be the same: the person with diabetes is listened too, time is taken to understand what is important for them, the PWD’s priorities are clear, and goals are realistic and checked along the way. The end results are not necessarily based on numbers or data points, but rather, just how well the person with diabetes is feeling about their diabetes, and if anything new has added to their daily burden. Reviews are focused on successes more than anything else.

My favourite ever diabetes educator, Cheryl Steele, gave an outstanding presentation on how HCPs can best work with people with diabetes to ensure we get the most from our technology.

I spoke with Cheryl after her talk (you can watch the video of our chat for Diabetes Australia at the end of today’s post), and she laughingly said that she could have said the most important things she wanted to say in 2 minutes, and with one slide that basically just said that HCPs need to be truly person-centred and listen to PWD.

But thankfully, she spoke a lot more than that and covered a number of different topics. But the thing that got to me – and the thing that I hope the predominantly HCP audience would take home and remember – was Chery urging her colleagues to focus on the positives.

Cheryl said, ‘The emphasis has to be on what you’re doing well’ and I feel that is a wonderful place to start and end healthcare consultations. I think about experiences where that has happened to me. Such as the time I went to my ophthalmologist after a few years of missing appointments and his reaction to seeing me was not to tell me off for not showing up previously, but instead to welcome me and say it was great I was there. I’ve never missed an appointment since.

How many PWD reading this have stories to share of times when they went into an appointment with data and all that was focused on was the out-of-range numbers? There are countless stories in online diabetes groups where HCPs have concentrated on the 10% out of range numbers rather than the 90% in range. Actually, even if only 10% of numbers were in range, that is 10% that are bang where they need to be!

Perhaps that’s what’s missing from diabetes appointments. Gold stars and elephant stamps!

There is something devastating about walking into an appointment and the first, and sometimes only, thing that is on the HCPs radar is numbers that are below or above the PWD’s target glucose range. I’ve sat in those appointments. I know the feeling of walking in and feeling that I’m tracking okay, only to have none of the hard work I’ve managed acknowledged and instead, only the difficulties addressed.

But then, I think about one of the first experiences with the endocrinologist I have been seeing for twenty years. Without judgement, she acknowledged that I wasn’t checking my glucose much, and asked if I felt that I could start to do one check every Wednesday morning when I woke up. I said that it seemed like such a pathetic goal to set, but she gently said, ‘One is more than none’. The focus was not on what I wasn’t achieving. It was on what I could.

What a wonderful motivator that is.

Disclosures

Thanks to the Australian Diabetes Society and Australian Diabetes Educators Association, organisers of the Australasian Diabetes Congress for complimentary registration to attend the conference. This gave me access to all the sessions.

I work for Diabetes Australia and the video shared is part of the organisations Facebook Live series. I am sharing here because is relevant to this post, not because I have been asked to.

As usual, no one has reviewed this piece before I hit publish (which is unfortunate because I could really do with an editor).

Yesterday, the Australian vaccine rollout was expanded to include children. This follows the TGA approving the use of the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine for children in the 12 – 15 year age group. ATAGI responded by including children with diabetes in that age group into Phase 1B, meaning they are eligible right now for a jab (provided, of course, they can find one…!).

Already I’m seeing in diabetes online discussions some parents of kids with type 1 diabetes saying their child will not be getting the vaccine, stating that the reason for that decision is because their type 1 diagnosis came shortly after one of their childhood vaccines.

And so it seems a good time to revisit this post that I wrote back in 2017. It has a very long title that could have been much more simply: correlation ≠ causation.

It is understandable to want to find a reason for a health issue. Being able to blame something means that we can, perhaps, stop blaming ourselves. I imagine that for parents kids with diabetes that desire to find something – anything – to point to would come as somewhat of a relief. But there is absolutely no evidence to suggest that vaccines are that reason.

Unfortunately, the idea that vaccines are the root of all evil and cause everything under the sun is a myth that is perpetuated over and over in antivax groups; groups where science, evidence and logic goes to die. Vaccines save lives and they are safe. Anyone who says otherwise is lying.

My sixteen year old is not in a priority group and cannot be vaccinated just yet, but she is ready to go as soon as her phase has the green light. All the adults nearest and dearest to her – her parents, grandparents, aunts and uncle, friends’ parents – are fully vaccinated now, and she knows what a privilege it is to be in that situation. She understands that with that privilege comes responsibility to do what you can to protect vulnerable cohorts in the community. And she also understands that vaccines are safe and they save lives.

If you are feeling unsure about getting a COVID vaccine – for you or your child – please speak with your GP. Don’t listen to someone in a Facebook group. And that may come as a surprise to anyone who knows how important I consider peer support and learning from others in our community, but to them I say this: I listen to and learn from people in the diabetes community because they don’t suggest anti-science approaches. They talk about support, and provide tips and tricks for living with diabetes. If anyone tells me to ignore doctors (because all they care about is getting rich), or to stop taking my insulin (because there is a natural supplement that will do the trick), I would block them as quickly as I could. Science works. Science is why people with diabetes are alive today. Science is why we have vaccines. Trust science. THAT’S what makes sense.

__________________________________________________________________________

In the next couple of weeks, our kid gets to line up for her next round of immunisations. At twelve years of age, that means that she can look forward to chickenpox and Diphtheria-Tetanus-Pertussis boosters, and a three-dose course of the HPV vaccine.

When the consent form was sent home, she begrudgingly pulled it out of her school bag and handed it to me. ‘I have to be immunised,’ she said employing the same facial expressions reserved for Brussels sprouts.

She took one look at me and then, slightly sheepishly, said, ‘I don’t get to complain about it, do I?’

‘Nope,’ I said to her. ‘You don’t get to complain about needles because…well because…suck it up princess. No sympathy about needles from your mean mamma! And you have to be vaccinated because that’s what we do. Immunisation is safe and is a really good way to stop the spread of infectious diseases that not too long ago people died from. And herd immunity only works if…’

‘….if most people are immunised so diseases are not spread,’ she cut me off, finishing my sentence. I nodded at her proudly, signed the form and handed it back to her. ‘In your bag. Be grateful that you are being vaccinated. It’s a gift.’ (She mumbled something about it being a crappy gift, and that it would be better if she got a Readings gift voucher instead, but I ignored that.)

Over the weekend, the vaccination debate was fired up again with One Nationidiot leader, Pauline Hanson, sharing her half-brained thoughts on the issue.

I hate that I am even writing about Pauling Hanson. I despise what she stands for. Her unenlightened, racist, xenophobic, mean, ill-informed rhetoric, which is somehow interpreted as ‘she just says what many of us are thinking’, is disgusting. But her latest remarks go to show, once again, what an ignorant and dangerous fool she is.

Her comments coincided with a discussion on a type 1 diabetes Facebook page about vaccinations preceding T1D. Thankfully, smart people reminded anyone suggesting that their diabetes was a direct result of a recent vaccination that correlation does not equal causation.

I get really anxious when there is discussion about vaccinations, because the idea that this is something that can and should be debated is dangerous. There is no evidence to suggest that vaccines cause diabetes (or autism or anything else). There is, however, a lot of evidence to show that they do a shed-load of good. And if you don’t believe me, ask yourself how many cases of polio you’ve seen lately. People of my parents’ generation seemed to all know kids and adults with polio and talk about just how debilitating a condition it was. And they know first-hand of children who died of diseases such as measles or whooping cough.

This is not an ‘I have my opinion, you have yours. Let’s agree to disagree’ issue. It is, in fact, very black and white.

A number of people in the Facebook conversation commented that their (or their child’s) diagnosis coincided with a recent vaccination. But here’s the thing: type 1 diabetes doesn’t just happen. We know that it is a long and slow process.

What this shows is that even if onset of diabetes occurs at (correlates with) the time of a vaccination, it cannot possibly be the cause.

When we have people in the public sphere coming out and saying irresponsible things about vaccinations, it is damaging. People will listen to Pauline Hanson rather than listen to a doctor or a researcher with decades of experience, mountains of evidence and bucket-loads (technical term) of science to support their position.

The idea that ‘everyone should do their own research’ is flawed because there is far too much pseudo-science rubbish out there and sometimes it’s hard to work out what is a relevant and respectable source and what is gobbledygook (highly technical term).

Plus, those trying to refute the benefit of vaccinations employ the age-old tactic of conspiracy theories to have people who are not particularly well informed to start to question real experts. If you have ever heard anyone suggesting: government is in the pockets of Big Pharma / the aliens are controlling us / if we just ate well and danced in the sunshine / any other hare-brained suggestion, run – don’t walk – away from them. And don’t look back.

I have been thinking about this a lot in the last couple of days. I have what I describe as an irrational fear that my kid is going to develop diabetes. It keeps me awake at night, makes me burst into tears at time and scares me like nothing else. If I, for a second, thought for just a tiny second that vaccinating my daughter increased her chances of developing diabetes, she would be unvaccinated. If I thought there was any truth at all in the rubbish that vaccines cause diabetes, I wouldn’t have let her anywhere near a vaccination needle.

But there is no evidence to support that. None at all.

Ask a group of people with diabetes about their experiences of stigma, and for examples of the sorts of things they’ve heard and before long you’ll be able to compile a top ten list of the most commonly heard misconceptions that have contributed to diabetes having an image problem. When I’ve asked about this recently, the main perpetrators of these seemed to be healthcare professionals. More on that later this week.

This year, in the Diabetes Australia National Diabetes Week campaign about diabetes-related stigma, two videos have been produced and they’re almost like a highlight reel of some of the stigmatising things people with diabetes hear.

Let me tell you something I found really interesting. As part of the testing of these, I showed them to a heap of people with diabetes and a heap of people without diabetes. The reaction from people with diabetes varied from sadness (including tears), to anger and frustration, and mostly, recognition in everything they saw.

The reaction from a number of people without diabetes was disbelief that this really happens. They simply couldn’t believe that people would be so insensitive; so cruel, so shaming.

However, for so many people with diabetes, this is our reality.

Here’s one of the two videos we produced. (You can watch the second one here.) Already, this is being shared widely in our own diabetes community. I’ve lost count of the places online I’ve seen this shared. Keep doing so, if you can. Because clearly, we need to get the message out to those without diabetes so they understand that not only is this sort of stigmatising behaviour harmful, but it is also horribly common. And it needs to stop.

DISCLOSURE

I work for Diabetes Australia, and I have been involved in the development of the Heads Up on Diabetes campaign. I’ve not been asked to share this – doing so of my volition, because I think the messaging is spot on. The words here are my own, and have not been reviewed prior to publication.

Today, I had my second COVID jab. I feel grateful, happy, relieved. I recognise how privileged I am to be living somewhere where I was able to access the vaccine. And I feel lucky. My tee wasn’t a deliberate choice when I threw it on this morning, but jeez, it sure does feel appropriate right about now.*

I also feel…

One step closer to not being so anxious.

One step closer to not worrying all the time.

One step closer to not calculating how close someone is standing.

One step closer to avoiding lockdowns.

One step closer to not having to check in everywhere we go.

One step closer to not thinking every sniffle, every cough is a sign of something more sinister than just a sniffle, just a cough.

One step closer to stressing less about my parents getting the virus.

One step closer to walking into places without first counting how many others are there.

One step closer to being free to meet up with friends in crowded bars.

One step closer to not assessing risk at every step, every move, every breath.

One step closer to not scrutinising testing numbers, vaccination numbers, virus numbers.

One step closer to borders opening.

One step closer to crossing borders.

One step closer to the Qantas Business lounge.

One step closer to getting on an aeroplane.

One step closer to walking the streets of New York.

One step closer to hearing Mike Stern at the 55 Bar on a Monday night.

One step closer to cinnamon buns in Copenhagen.

One step closer to more in-person diabetes peer support.

One step closer to presenting on a stage instead of a zoom room.

One step closer to IRL #docday°.

One step closer to hugging friends from far flung places.

One step closer to thanking my squad in person for keeping me going.

One step closer to kisses on the cheeks say hello.

One step closer to not having to get up at least once a week for 3am meetings for projects run outside of Australia.

One step closer to walking the halls of diabetes conferences again.

One step closer to this being over.

One step closer to life as we knew it, even if it will never be the same again.

*My tee wasn’t a deliberate choice when I threw it on this morning, and it wasn’t until I was on my way to getting my jab that I really though about it. There’s a story to that tee, and today, it feels pretty special.

In January 2020, I was in my favourite store in Melbourne (shout out to Sian at RMP Melbourne), and there, on the racks, was a white t-shirt, from Rabens Saloner, with ‘Lucky one’ printed across the front. Startled, I took in a sharp breath and lifted the shirt from it’s hanger, holding it up to me. And I flashed back the last day of EASD in Barcelona just a few months earlier, remembering…

I remembered how on that last day of the conference, walking between the hotel and the conference centre, I saw a stencil of the words ‘Lucky One’, the paint dripping from the words. It was on a concrete wall with nothing else around it. It summed up perfectly how I was feeling, so I snapped a pic to remind me.

Here is that photo…

Trawling Instagram today, this jumped out at me:

This is a fact. No correspondence will be entered into. It doesn’t matter if you like it some other way. There is no ‘But I like it with parsley’ or ‘I substituted chicken for the guanciale’, or ‘It tastes better with cream’. Because no. No, it does not. Or, if you believe it does, that’s fine, but what you have cooked is not carbonara. You’ve made up something different. Enjoy. Just don’t call it carbonara.

Italians are very strict with their food rules. Which is hysterical, because in my experience (from, you know, my own family), Italians generally don’t really like rules all that much. I remember hearing about a time when there was a lucrative cottage industry in Italy of tee-shirts with diagonal black lines across the front for people to wear instead of buckling up when seatbelts became mandatory. I am, in equal measure, amused, astonished and appalled at the audacity of it all (and alliterative too).

Anyway, back to carbonara. The ingredients for the recipe are not open to negotiation. If you want to make it for dinner tonight, you need eggs, guanciale, pecorino, black pepper and bucatini. È tutto!

Thank fuck diabetes isn’t that rigid!

I break rules, ignore rules and make up rules all the live-long day. Because that’s how I do it. Diabetes is an opinion. Work out yours, change it as you like, add different things, or change change them out. And go for it. And don’t let anyone – even loud, passionate Italians – tell you otherwise.

Totally irrelevant postscript of my favourite ever story of Italians breaking rules (which, by the way, I think would make a brilliant series)

Years ago, while in a very long queue at the Santa Maria de Monserrat monastery, Aaron and I got chatting to a nonna-aged Italian woman. After five minutes, she’d had enough, announced that Italians don’t queue and pushed her way to the front, ignoring the stern rules that were clear to everyone else. She returned ten minutes later to tell us the statue was a gorgeous sight, and that we were stupid for not following her. Two hours later, while still diligently lining up, we realised she was right.

Last night, my gorgeous friend Andrea tweeted how she had seen someone wearing a CGM on the streets of Paris. When she rolled up her sleeve to show him her matching device, he turned and walked away. ‘Guess you can’t be best friends with every T1D’, she wrote. ‘Diabetes in the Wild’ stories have been DOC discussion fodder for decades – including wonderful stories of friendships being started by a chance encounter, and less wonderful stories such as Andrea’s most recent encounter. I was reminded of the many, many times pure happenstance of random diabetes connection has happened to me.

There was the time I was waiting for coffee and another person in line noticed my Dexcom alarm wailing, and the banter we fell into was so comfortable – as if we’d known each other forever!

And that time that someone working the till at a burger flashed her CGM at me after seeing mine on my arm and we chatted about being diagnosed as young adults and the challenges that poses.

Standing in line, queuing for gelato, is as good as any place to meet a fellow traveller and talk about diabetes, right? That’s what happened here.

And this time where I spotted a pump on the waistband of a young woman with diabetes, and started chatting with her and her mother. The mum did that thing that parents of kids with diabetes sometimes do – looking for a glimpse into her child’s future. She saw that in my child, who was eagerly listening to the exchange. But I walked away from that discussion with more than I could have given – I remember feeling so connected to the diabetes world in that moment, which I needed so much at the time.

I bet that the woman in the loos at Madison Square Garden wasn’t expecting the person who walked in at the exact moment she was giving herself an insulin injection to be another woman with diabetes. But yeah, that happened…

I’ll never forget this time that I was milliseconds from abusing a man catcalling me out his car window, until I realised he was yelling out at to show me not only our matching CGMs, but also the matching Rockadex tape around it. My reaction then was ridiculous squealing and jumping up and down!

Airports have been a fruitful place to ‘spot diabetes’, such as the time my phone case started a discussion with a woman whose daughter has diabetes, except we didn’t really talk about diabetes. And the time another mum of a kid with diabetes was the security officer I was directed to at Amsterdam’s Schiphol Airport. She was super relaxed about all my diabetes kit, casting her eyes over it casually while telling me about her teenage son with diabetes.

The follow up to this time – where I introduced myself to the young mum at the next time who I overheard speaking about Libre, and saying how she was confused about how it worked and how to access it – but not really being all that sure about it, is that she contacted me to let me know that she’d spoken with their HCP about it, had trialled it and was now using it full time. She told me that managing diabetes with toddler twins was a nightmare, and this made things just a little easier.

Sometimes, seeing a stranger with diabetes doesn’t start a conversation. It can just an acknowledgment, like this time at a jazz club in Melbourne. And this time on a flight where we talked about the Rolling Stones, but didn’t ‘out ourselves’ as pancreatically challenged, even though we knew …

But perhaps my favourite ‘Diabetes in the Wild’ story is one that, although I was involved, I didn’t write about. Kerri Sparling wrote about it on her blog, Six Until Me. Kerri was in Melbourne to speak at an event I was organising, and one morning, we met at a café near my work. We sat outside drinking our coffees, chatting away at a million miles an hour, as we do, when we noticed a woman at the next table watching us carefully. We said hi, and she said that she couldn’t help listening to us after she heard us mention diabetes. She told is her little girl – who was sitting beside her, and was covered in babycino – had recently been diagnosed. I will never forget the look on the mother’s face as two complete strangers chatted with her about our lives with diabetes, desperately wanting her to know that there were people out there she could connect with. I also remember walking away, hoping that she would be okay.

Five years later, I found out she was okay – after another chance encounter. I was contacting people to do a story for Diabetes Australia and messaged a woman I didn’t know to see if she, along with her primary aged school daughter would be open to answering some questions. Turns out, this was the woman from Kerri’s and my café encounter. She told me how that random, in the wild conversation made her feel so encouraged. She said that chance meeting was the first time she’d met anyone else with diabetes. And that hearing us talk, and learning about our lives had given her hope at a time when she was feeling just so overwhelmed.

I know that not everyone wants to be accosted by strangers to talk about their health, and of course, I fully respect that. I also know there are times that I find it a little confronting to be asked about the devices attached to my body. But I also know that not once when I’ve approached someone, or once when someone has approached me has there been anything other than a warm exchange. I so often hear from others that those moments of accidental peer support have only been positive, and perhaps had they not, we’d all stop doing it. It’s a calculated risk trying to start a conversation with a stranger, and I do tread very lightly. But I think back to so many people in the wild stories – the ones I’ve been involved in, and ones shared by others – and I think about what people say they got out of them and how, in some cases they were life changing. A feeling of being connected. The delight in seeing someone wearing matching kit. The relief of seeing that we are so alone. The sharing of silly stories, and funny anecdotes. And in the case of that mum with a newly diagnosed little kid, hope.

Today’s post is dedicated to Andrea whose tweet kicked off this conversation in the DOC last yesterday. Thanks for reminding me about all these wonderful chance meetings, my friend.