You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Devices’ category.

Do you remember life before diabetes? It’s getting harder and harder for me to. I had 24 years without diabetes, and occasionally, I’ll look at a photo from the BD years and think about how much simpler my days were.

Today, I’m wondering how much I remember diabetes before I started using automated insulin delivery (AID). It’s been eight years. Eight years of Loop. Happy loopiversary to me! Diabetes BL (before Loop) felt heavier. And scarier. I remember those months just after I started looping and how different things felt. I remember the better sleep and the increased energy. I remember a lightness that I hadn’t experienced since I was diagnosed.

That’s now my “diabetes normal”. Life with Loop is simply easier than life BL. On the very rare occasions I’ve had to DIY diabetes, it’s been a jolt as I’ve realised just how truly bad I am at diabetes. Embarrassingly bad.

While there was a stark difference back then between people who were using DIYAPS and those who were using interoperable devices on the market, today that difference is less. AID systems are not just for people who choose to build one for themselves. These days, it’s so great to know that there are commercial systems available which means more people have access to AID. We can debate which algorithm is better or whether a commercial or an open-source system is better, but I think that’s a little pointless. If people are doing less diabetes and feeling happier, better and less burdened, it doesn’t matter what they’re using. Your diabetes; your rules!

Eight years on, and despite there being commercial systems I could access, I’ve decided to keep using Loop – the same system I started on 8 years ago. The changes I’ve made are the devices with which I am using Loop. My pink Medtronic pump has been retired, along with the Orange Link (which was obviously in a pink case). Instead, I now use Omnipod, a single device instead of two which has further simplified my diabetes. It’s also meant not worrying about a working back up Medtronic pump, and it means carrying less bulky supplies when travelling.

These may all seem like little things, but they add up.

My decision to not move to a commercial system has been based on a couple of different reasons. I always said that I wouldn’t move to something that required a trade-off whereby any of the convenience of Loop was compromised. I’ve been blousing from my iPhone or Apple watch since 2017, and I refused to let that go. In my mind, having to wrangle my pump from my bra or carry an additional PDM to bolus was a step backwards. Of course, this is now available on some commercial systems, and it’s been super cool to see diabetes friends have access to something that does make diabetes a little less intrusive.

The customisability of Loop has meant that my target levels are set by me and me alone. The lower limit on commercial systems is not what I like mine set at. I wasn’t prepared to sacrifice the flexibility of personalised settings fora one-size-fits-all approach.

I do understand that there are pros to having a commercial system. Having helplines to trouble shoot and customer support on call is certainly a positive. Knowing that an annual Loop rebuild (always anxiety inducing because …well, technology?) is upcoming is stressful. And the worry that the update will break something that’s been working perfectly.

And yet, measure for measure, the decision to continue to use Loop has been very easy.

I still thank the magicians behind open-source technologies for their brilliance and generosity every single day. I’m grateful for the algorithm developers, the people who have written step by step instructions that even I can follow, and I am so thankful for the people who have tried to make devices more affordable. I believe that device makers do genuinely want to make diabetes simpler and help ease the load of diabetes. But in my mind, it’s undeniable that user-led developments have been more successful in actually making diabetes easier. These magicians know firsthand just what it means to claw back from diabetes.

In the end, the goal for me has always been clear: I want diabetes to intrude in my life as little as possible, and I will avail myself of anything that helps. It’s why I continue to use an Anubis even though there is no out of pocket cost for G6 transmitters. Using an Anubis means I change my sensor when it’s getting spotty, not when the factory setting insists, and the transmitter last six instead of three months. See? Fewer diabetes tasks. Less diabetes. That’s the whole point. (And it’s also why I’m hesitant about moving to G7)

When I try to quantify how much less diabetes, I just come back to Justin Walker and his presentation at Diabetes Mine’s DData back in 2018 when he said ‘By wearing Open APS, I save myself about an hour a day not doing diabetes’. Eight years down the track, that’s 2,922 hours I’ve gained back. That’s almost 122 days. It may be thirty seconds here, a minute there. But it adds up. And that time is better in my pocket than in diabetes’.

And so, here I am. Eight years on. With diabetes in the background as much as it can be with the tools I have available to me. I still really don’t like diabetes. I still really resent it takes up the time and brain space it does, and I still want a cure for all of us. Damn, we deserve that.

But in the meantime, I’m going to keep leaning into what the community has done for the community and know how lucky I am to benefit from that knowledge and expertise. Never bet against the T1D community. We know exactly what diabetes takes from us every day. And exactly what it takes to give some of it back.

More on my experiences with Loop

That time I scared the hell out of healthcare professionals

What looping on holidays looks like

A list of how Looped changed my diabetes life (and all of it is still relevant today!)

Postscript

As ever, I’m very aware of my privilege. Access to AID is nowhere near where it should be. If we look at the Australian context, insulin pumps remain out of range for so many people with T1D thanks to outdated funding models. Remember the consensus statement developed last year? And beyond our borders, technology access varies significantly. As a diabetes community, we are not all beneficiaries from this tech until every single person with diabetes has access. And that starts with affordable, uninterrupted access to insulin, right through to the most sophisticated AID systems, to preventative treatments, to cell therapies.

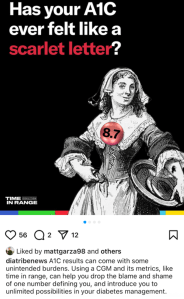

Earlier this week, diaTribe shared this on their Instagram:

It did not sit well with me at all. And I don’t understand the reference to stigma.

A1C is flawed. People with diabetes have been saying this for decades. To have our overall diabetes management measured by an average that gives no nuance to other factors is not a good way to assess health or guide treatment.

CGM changed all that, with visibility into just what is going on with glucose levels at all times. I finally understood why I was so tired some mornings, despite eight solid hours of sleep with in-range numbers at bedtime and at waking. I saw the rollercoaster nights, or the hours at time I was low. It became very clear that my nighttime glucose adventures were exhausting me.

As more people had access to CGM, TIR was heralded as the new gold measuring standard. And it was everywhere. I wrote and spoke about it a lot because the real-time data gave me a clearer understanding of my diabetes. But with that excitement came a gnawing discomfort: were we just swapping out one metric for another?

After a couple of years of TIR, and with the advent of newer, smarter AID systems there was a new kid on the block: Time in Tight Range (TITR). Target upper and lower limits were tightened and there were expectations of remaining within those ranges.

I nodded along because I was, for the most part, comfortably sitting within those number thanks to Loop. And yet, my discomfort grew. More pressure, more expectations on people with diabetes based solely on numbers, and a continued widening of the gap between people with access to tech and those without.

At ATTD a couple of months ago, there was the announcement of a new metric: Time in Normo-Glycaemia – TING! (There is no exclamation mark after the acronym, but it reminds me of the celebratory sound my kitchen timer makes when a cake is done baking, and that deserves festive punctuation.) And horrifyingly, to this #LanguageMatters boffin, the new acronym includes the word ‘normo’. Language position statements have always, always advised against using the word normal/normo. The word shapes attitudes that contribute to stigma. In one study, 85% of PWD surveyed found the word unacceptable.

These measures still focus on one thing: our glucose numbers. There are goals for the percentage of time each day we should be aiming to be in (ever-tightening) range. So, effectively, the HbA1c percentage has been replaced with time in range percentage. It’s still focusing on nothing more than numbers. It still sets us up for a pass/fail framework.

A1C, in itself, is not stigmatising. It’s a number. The language used when discussing A1C can be stigmatising. Attributing success in diabetes to an A1C number can be stigmatising. Being told we’re failing for not reaching an A1C of a certain number is stigmatising. But all of those things are true of TIR.

Before anyone comes at me and tells me that PWD should be able to have numbers within a tight range, of course that’s true. But isn’t that already the goal of our diabetes management? Isn’t that the point with all the glucose measuring, insulin dosing, and considering the bazillion other things we do to manage diabetes? I don’t know anyone with diabetes who does the work with a goal of glucose number of 17.0mmol/l; an HbA1c of 14%; a TIR/TITR/TING of 11%.

But replacing one measure for another still traps us in a numbers-only mindset. How is ‘What’s your TIR?’ really any different to ‘What’s your A1C?’ Does it free us from being metrics-focused? (Some might argue that it ties us to numbers even more with daily updates about how we’re tracking.) Does it address stigma?

I’m not sure it does. I’m not convinced that there is any relevance at all to stigma in this conversation. And I’m a little annoyed at the conflation. Diabetes-related stigma is very topical now, thanks to important efforts by PWD, community groups, researchers and clinicians in the diabetes space. If I was being cynical, I’d suggest that this is an opportunistic attempt to jump on the buzz movement of the moment without meaningfully engaging with what stigma really is or how any type of metric can contribute to it, depending on how it’s framed and used.

Postscript – but possibly the most important part…

And finally, but perhaps most importantly: the very idea that we are suggesting this is the gold standard when it is inaccessible to the vast majority of people with diabetes is just so out of touch. According to the diaTribe article that accompanied the Instagram post I shared earlier, worldwide 9 million people are currently using CGM as part of their diabetes management. The IDF’s latest Atlas data, (launched last month) reports that there are about 589 million adults (20-79 years) with diabetes across the world. That doesn’t include children and young people. (1.8 million young people are estimated to be living with T1D.)

Isn’t this one way stigma takes a hold? When we’re talking about targets that are only available to the small fraction of the diabetes community who can access the tools to achieve them. Setting standards around tech that most can’t obtain doesn’t just ignore reality—it reinforces the stigma of not measuring up.

So often, there is amazing work being done in the diabetes world that is driven by or involves people with lived experience. Often, this is done in a volunteer capacity – although when we are working with organisations, I hope (and expect) that community members are remunerated for their time and expertise. Of course, there are a lot of organisations also doing some great work – especially those that link closely with people with diabetes through deliberate and meaningful community engagement.

Here are just a few things that involve community members that you can get involved in!

AID access – the time is now!

It’s National Diabetes Week in Australia and if you’ve been following along, you’ll have seen that technology access is very much on the agenda. I’m thrilled that the work I’ve been involved in around AID access (in particular fixing access to insulin pumps in Australia) has gained momentum and put the issue very firmly on the national advocacy agenda, which was one of the aims of the group when we first started working together. Now, we have a Consensus Statement endorsed by community members and all major Australian diabetes organisations, a key recommendation in the recently released Parliamentary Diabetes Inquiry and widening awareness of the issue. But we’re not done – there’s still more to do. Last week I wrote about how now we need the community to continue their involvement and make some noise about the issue. This update provides details of what to do next.

And to quickly show your support, sign the petition here.

Language Matters pregnancy

Earlier this week we saw the launch of a new online survey about the experiences of people with diabetes before, during and after pregnancy, specifically the language and communication used around and to them. Language ALWAYS matters and it doesn’t take much effort to learn from people with diabetes just how much it matters during the especially vulnerable time when pregnancy is on the discussion agenda. And so, this work has been very much powered by community, bringing together lots of people to establish just how people with diabetes can be better supported during this time.

Congratulations to Niki Breslin-Brooker for driving this initiative, and to the team of mainly community members along with HCPs. This has all been done by volunteers, out of hours, in between caring for family, managing work and dealing with diabetes. It’s an honour to work with you all, and a delight to share details of what we’ve been up to!

Have a look at some of the artwork that has been developed to accompany the work. What we know is that it isn’t difficult to make a change that makes a big difference. The phrases you’ll see in the artworks that are being rolled out will be familiar to many people with diabetes. I know I certainly heard most of them back when I was planning for pregnancy – two decades ago. As it turns out, people are still hearing them today. We can, and need to change that!

You can be a part of this important work by filling in this survey which asks for your experiences. It’s for people with diabetes and partners, family members and support people. They survey will be open until the end of September and will inform the next stage of this work – a position statement about language and communication to support people with diabetes.

How do I get involved in research?

One of the things I am frequently asked by PWD is how to learn about and get involved in research studies. Some ideas for Aussies with diabetes: JDRF Australia remains a driving force in type 1 diabetes research across the country, and a quick glance at their website provides a great overview. All trials are neatly located on one page to make it easy to see what’s on the go at the moment and to see if there is anything you can enrol in.

Another great central place to learn about current studies is the Diabetes Technology Research Group website.

ATIC is the Australasian Type 1 Diabetes Immunotherapy Collaboration and is a clinical trials network of adult and paediatric endocrinologists, immunologists, clinical trialists, and members of the T1Dcommunity across Australia and New Zealand, working together to accelerate the development and delivery of immunotherapy treatments for people with type 1 diabetes. More details of current research studies at the centre here.

HypoPAST

HypoPAST stands for Hypoglycaemia Prevention, Awareness of Symptoms and Treatment, and is an innovative online program designed to assist adults with type 1 diabetes in managing their fear of hypoglycaemia. The program focuses on hypoglycaemia prevention, awareness of symptoms, and treatment, offering a comprehensive range of resources, including information, activities, and videos. Study participants access HypoPAST on their computers, tablets, or smartphones.

This study is essential as it harnesses technology to provide practical tools for better diabetes management, addressing a critical need in the diabetes community. By reducing the anxiety associated with hypoglycaemia and improving symptom awareness and treatment strategies, HypoPAST has the potential to enhance the quality of life for individuals with type 1 diabetes.

The study is being conducted by the ACBRD and is currently recruiting participants. It’s almost been fully recruited for, but there are still places. More information here about how to get involved.

Type 1 Screen

Screening for T1D has been very much a focus of scientific conferences this year. At the recent American Diabetes Association Scientific Sessions, screening and information about the stages of T1D were covered in a number of sessions and symposia. Here in Australia. For more details about what’s being done in Australia in this space, check out Type 1 Screen.

And something to read

This article was published in The Lancet earlier in the year, but just sharing here for the first time. The article is about the importance of genuine consumer and community involvement in diabetes care, emphasising the benefits and challenges of ensuring diverse and representative participation to meet the community’s needs effectively.

I spend a lot of time thinking a lot about genuine community involvement in diabetes care and how people with diabetes can contribute to that ‘from the inside’. And by ‘inside’ I mean diabetes organisations, industry, healthcare settings and in research. I may be biased, but I think we add something. I’m grateful that others think that too. But not always. Sometimes, our impact is dismissed or minimised, as are the challenges we face when we act in these roles. I don’t speak for anyone else, but in my own personal instance, I start and end as a person with diabetes. I may work for diabetes organisations, have my own health consultancy, and spend a lot of time volunteering in the diabetes world, but what matters at the end of the day and what never leaves me is that I am a person living with diabetes. And I would expect that is how others would regard me too, or at least would remember that. It’s been somewhat shocking this year to see that some people seem to forget that.

Final thoughts…

Recently when I was in New York at Breakthrough T1D headquarters, I realised just how many people there are in the organisation living with the condition. It’s somewhat confronting – in a good way! – to realise that there are so many people with lived experience working with – very much with – the community. And it’s absolutely delightful to be surrounded by people with diabetes at all levels of the organisation – including the CEO. But you don’t have to have diabetes to work in diabetes. Some of the most impactful people I’ve worked with didn’t live with the condition. But being around people with diabetes as much as possible was important to them. It’s really easy to do when people with diabetes are on staff! I first visited the organisation’s office years ago – long before working with them – to give a talk about language and diabetes. One of the things that stood out for me back then was just how integral lived experience was at that organisation. From the hypo station (clearly put together by PWD who knew they would probably need to use the supplies!) to the conversations with the team, community was in the DNA of the place. As staff, I’ve now visited HQs a few times, and I’ve felt that even more keenly. Walking through the office a couple of weeks ago, I saw this on the desk of one of my colleagues and I couldn’t stop laughing when I saw it. IYKYK – and we completely knew!

DISCLOSURES (So many!)

I was part of the group working on the AID Consensus Statement, and the National AID Access Summit that led to the statement.

I am on the team working on the Language Matters Diabetes and Pregnancy initiative.

I was a co-author on the article, Living between two worlds: lessons for community involvement.

I am an investigator on the HypoPAST study.

My contribution to all these initiatives has been voluntary

I am a representative on the ATIC community group, for which I receive a gift voucher honorarium after attending meetings.

I work for Breakthrough T1D (formerly JDRF).

‘A fire has been lit.’ They were the words I wrote in my first post about AID access in Australia earlier this year.

There are some truths about grassroots advocacy that I have always known to be consistent. It has to come from community. If the issue isn’t important to a significant number of community members, nothing will happen. Advocacy efforts are truly organic. To be real and honest to the consultation process, there cannot be any pre-conceived ideas about the results of that consultation. Or rather, there needs to be an acceptance that agility and swift pivots are necessary if that is what the community directs. And there needs to be meaningful engagement every step of the way, with a genuine belief that expertise lies with all stakeholders, in particular people with lived experience. I am so pleased that this was the foundation and ran through every single step of the way with our AID grassroots advocacy over the last few months.

After months of working and meeting with the community, it was time to bring all stakeholders together. In May, I was so honoured to co-chair the National AID Access Summit with Professor Peter Colman. Again, this was always part of the plan – a clinician and a person with lived experience chairing the meeting to signpost how critical it is to have input from different cohorts. Unashamedly, we had almost as many people with lived experience as others in attendance, because that’s the way to centre people with diabetes. We also had independent facilitators directing traffic. This was important because we didn’t want there to be ownership of this work by any individuals or organisations. This wasn’t anyone’s show; it wasn’t anyone’s vanity project. This was a community endeavour. You know, with and by for people with T1D, not for us!

The outcome from the Summit, and the work that led to it, is a consensus statement that offers clear, concise recommendations. Stars aligned, and the statement was completed the same week as the Parliamentary Inquiry into Diabetes report was tabled. And that alignment was even more significant, when our recommendations neatly mirrored those in the report.

The consensus statement can be accessed and shared here, as well as from the survey for equitable access to AID that has been signed by almost 6,000 people.

Now, it’s over to the community. We have recommendations from the parliamentary inquiry, but that’s not enough. It’s now time to do the work to turn that into policy. And that’s where people in the community come to the fore once again. Today, I wrote to my local MP to ask for a time to meet with him, sharing with him the consensus statement. I am going to highlight just how important this tech is and how it’s not fair that only those of us who can afford it have access. The better outcomes AID delivers should be available to everyone with T1D, not just those who can afford private health insurance, or meet the eligibility for our Insulin Pump Program.

If you’re interested and able to get involved, please do. It is the groundswell of community efforts that has in the past seen some truly remarkable results. If we look back to the path to CGM access for all people with T1D, the community stepped up in truly remarkable ways. It took time, and it took energy, but we got there because people with diabetes never stopped pushing for it. Being able to access CGM really mattered to people with T1D and their families and that drove the ‘never give up’ attitude to get it done.

Now, it’s time for all Aussies with T1D to have access to AID if they choose. This update from the Access to AID Survey has some great ideas about how you can get involved. And reach out to me if you want any ideas.

Yesterday, the Australian parliamentary Inquiry into Diabetes report was launched. After eighteen months of countless submissions, interviews, and meetings with diabetes stakeholders from across the country, the report has been handed down with 23 recommendations aimed at improving the lives of Australians living by diabetes. There was much discussion and celebration among those of us advocating for increased access to Automated Insulin Delivery (AID) systems, particularly with the recommendation to expand funding for insulin pumps, which would increase the number of people using AID. Inquiry Chair Mike Freelander expressed strong support for this initiative in his report foreword.

It truly has been remarkable to see the community advocacy seed that was planted back in March in Florence absolutely flourish. Being involved with a dedicated group of people who have worked tirelessly, all volunteering our time to develop a single-issue advocacy movement is a wonderful demonstration of community commitment. We were clear from the beginning about what our aim was – equitable access to AID for Australians with T1D, with a specific focus on addressing the AID component that wasn’t already funded: insulin pumps. With the voices of people with lived experience centred in this work, a survey was launched, community discussions ran wild, a summit was convened and run and very soon a consensus statement will be launched to assist with the next steps of lobbying to have the inquiry recommendation transformed into a policy decision. This was for the T1D community, with the T1D community and by the T1D community. Focused and tailored.

Many of the recommendations in the report focus on Type 2 diabetes (T2D), and people with T2D deserve the same focused and tailored attention. This isn’t about separating the types of diabetes and dividing advocacy efforts. It’s about targeted and impactful initiatives that highlight and address the unique challenges faced by people with T2D. There are undoubtedly considerations specific to T2D, and they should receive the attention and expertise they deserve – not be treated as an addendum to T1D efforts.

And it needs to be driven by the community. I know how difficult it can seem to find adequate representation and advocacy for T2D. When we look at the #dedoc° voices scholarship program, the number of people with T1D far outweighs the number of people with T2D. If we examine other community groups and initiatives, we see that T1D is overrepresented. But there are remarkable advocates with T2D out there already. I met some incredible advocates when I was involved in the DEEP network. There is a T2D community out there, and there will be people who not only rise to the occasion but will drive it with their passion and lived experience expertise. They may not congregate or use the same channels that the T1D community uses, or they may be less visible, but that doesn’t mean they are not there. It’s laziness on behalf of all of us who have said we can’t find people to speak or be involved in T2D community efforts. We have expected them to be in the same place that people with T1D are. Look further. Look harder. Look better. Remember what Chelcie Rice says ‘You can’t just put pie in the middle of the table. Deliver the pie to where they are.’ Deliver the pie to where they are.

This is an opportunity to move the discussion about T2D beyond personal responsibility, which is what public-facing campaigns have largely focused on to date. The stigma and blame these campaigns generate are often harmful. And one result of that stigma is community members who are reluctant to come forward. I mean, would you like to be a spokesperson for advocacy efforts about T2D if messaging has blamed you for getting T2D in the first place? I know I certainly wouldn’t.

This is an opportunity for real, meaningful systemic change that addresses failures in healthcare access, education, and prevention. Junk food advertising to kids, sugar taxes, and finding ways for the healthier choice to be as easy as the less healthy choice are all critical steps. Addressing food insecurity, socio-economic disparities, and providing better healthcare access are also necessary. All of these measures address the root causes on a large scale, rather than pointing the finger at individuals and telling them it’s their fault.

We can do hard things and be bold. But it will need a collective effort and strong leadership.

And while we’re at it, remember where to look for the innovation and advocacy that has driven change. The community. Access to continuous glucose monitors (CGMs), insulin pumps, and other advancements has all started in the community and been picked up and run with by other stakeholders to make things happen.

People with T2D deserve the same level of advocacy and support. Now seems like a fine time to do that. And as a person with T1D, I am here to support and be led by my T2D peers.

There’s been a lot said about AID equity over the last few weeks. Actually, way longer than that. The momentum may have ramped up since a meeting at ATTD in Florence, but this has been something that the community has been speaking about for ages. In fact, I found a policy document advocating for pump access for all people with T1D from ten years ago, and I spoke at its launch in Parliament House . In there is a direct quote from me: ‘I decided to start using an insulin pump because my husband and I wanted to start a family. I knew of the importance of tight diabetes management prior to and during pregnancy. Insulin pump therapy gave me the ability to tailor and adapt my insulin doses to provide me with the best possible outcome – a beautiful healthy daughter.’

For the last six years I’ve been talking about how transformative AID has been with quotes like this: ‘Short of a cure, the holy grail for me in diabetes is each and every incremental step we take that means diabetes intrudes less in my life. I will acknowledge with gratitude and amazement and relief at how much less disturbance and interruption there is today, thanks to LOOP (AID).’

But enough from me. This is an issue that the T1D community owns and is engaged in. Last week at the #dedoc° symposium at the Diabetes UK Professional Conference, brilliant diabetes advocate Emma Doble spoke about patient and public involvement, highlighting how it refers to being with or by the community, not to, about or for them. The AID equity work underway is definitely with and by. It’s something community is calling for as a priority. A visit to any online T1D group will demonstrate that, and spending any time speaking directly with community will provide insight into the number of people who simply cannot access AID because they cannot afford an insulin pump. This is standard T1D care. The evidence is clear.

To get an idea of just how the T1D, and broader diabetes community feels, have a read of their own words. These comments are from the Make Automated Insulin Delivery affordable for all Australians with type 1 diabetes petition. They’re all publicly available, so you can click here to read the comments I’ve shared and many, many more.

‘Why would you bet against the type 1 community?’ That was a question asked in a session at the ISPAD conference a couple years ago. It wasn’t someone with T1D drawing attention to the community. Instead, it was said by someone working in global health who had seen the remarkable efforts such as the #WeAreNotWaiting movement and grassroots, peer-led education initiatives in low-income countries. These efforts have driven change and improved lives of people with diabetes. They have been led by those with lived experience and supported by other diabetes stakeholders. But the starting point is people directly affected by diabetes identifying a problem, solving it and leading the way. In the history of diabetes – from the first home glucose meters, to building systems leveraging off existing technologies, to global advocacy movements – community powered initiatives have been a driving force for change.

And so, here we are today, coming together once again to advocate for better equity and fairness for all people with type 1 diabetes, this time in Australia, and this time advancing access to automated insulin delivery devices (AID).

Insulin pump funding is broken. AID is standard care and yet far too many people are left unable to use the tech because of how pumps are funded in Australia. Right now, unless a person with T1D has the right level of private health insurance, or meets the criteria for the Insulin Pump Program, they must find the funding for an insulin pump. That needs to change.

We know how to do this in Australia. The reason that pump consumables are on the NDSS is thanks to community advocacy efforts back in the early 2000. And more recently massive community noise helped to get CGM onto the NDSS for all Australians. Of course, these wins worked because everyone was involved in advocacy: people with lived experience of diabetes, healthcare professionals and HCP professional groups, researchers, diabetes community groups and organisations and industry. What a lot of noise we can make when we’re singing from the same song sheet!

Right now, attentions are razor focused on improving access to automated insulin delivery systems because the evidence is clear: AID reduces diabetes distress, improves quality of life, and (for those who like numbers!), help with glucose levels. And as an added bonus for the bean counters – it’s a smart, cost-effective investment for our health system.

If AID is standard care, financial barriers preventing people from accessing it need to be eliminated.

And that’s where we would love your help.

Please sign and share the petition that has been started by Dr Ben Nash and supported by a group of people with T1D (including me). Petitions are a great way to get people talking and interested in a topic. It builds momentum and helps contribute to whole of community conversations. While we know the T1D community is already on board, we’ve now seen a number of HCPs, community groups and diabetes organisations share and promote the petition and are keen to get involved with broader advocacy efforts. That’s pretty cool!

Postscipt:

Understandably, there are questions about why this work is specific to T1D technology access. That’s a fair question and I think that our very own Bionic Wookiee provided an excellent explanation of that when he said this in a social media post earlier this week:

‘AID systems were developed for T1D (where they can track all the insulin going into the system without having to cope with the body’s variable insulin generation). So right now they mainly apply to T1D…

Expanding CGM and pump access to people with other forms of diabetes than just T1D is important for the future. Having wider access to AID for the T1D population will be a beach-head for that.‘

And in a conversation I had about this with UK diabetologist Partha Kar yesterday he cautions that there needs to be a starting point because the sheer numbers of diabetes can be daunting and tend to scare policy makers. He also points out that when it comes to outcome modifying interventions, technology is THE thing in T1D, whereas in other types of diabetes there are other options. I’ll add that those other options often have stronger evidence which is why they already have funding.

Hasn’t it been terrific this week seeing a couple of great news stories in the T1D tech world? Our friends across the ditch in NZ have welcomed an announcement from medical regulatory board Pharmac that all people with type 1 diabetes will have access to CGM and automated insulin delivery devices (AID). Meanwhile, this week saw the start of a five-year national roll out of AID in England and Wales which recommends access be granted to children and adolescence (under 18 years) with T1D, pregnant people with T1D and adults with T1D with an A1c higher than 7%.

So, where is Australia when it comes to people with T1D being able to affordably access automated insulin delivery devices?

Let’s start by highlighting the positives. There’s so much to be grateful for here in Australia. The NDSS continues to be a shining light for Australians with diabetes. Syringes and pen tips are free at NDSS collection points and BGL strips are subsidised. Since 2004, insulin pump consumables have been on the NDSS, CGM sensors and transmitters have been subsidised since 2022. Insulin is heavily subsidised by the PBS.

But even with these benefits diabetes remains costly, and the playing field isn’t level. Pumps remain out of reach for many Australians. Without private health insurance or meeting eligibility to apply for the government funded Insulin Pump Program, people with T1D are required to find up to $10,000 for an insulin pump. That’s simply not affordable and it means that Australians with T1D can’t access AID.

With AID providing real life-changing benefits and significant reduction in diabetes burden, now is the time to ensure that the tech is available to everyone with T1D who wants it – not just those who can afford it. And that means that it’s time to equitably fund the missing piece of the AID puzzle: Pumps.

A fire has been lit. From a small meeting at ATTD in Florence to catch ups, coffees and phone calls back home, the groundswell has well and truly started. People with diabetes are central to this, working closely with motivated and determined HCPs and diabetes community organisations. There is a united focus on what needs to be done: affordable insulin pumps so AID is a reality for every Australian with type 1 diabetes who chooses. And excitedly, there seems to be an appetite for this from policy makers.

So what can we learn from the recent successes in NZ and the UK? Well, it’s exactly what we know from our previous advocacy experiences and wins here in Australia. A united stakeholder approach is critical with everyone from individuals with diabetes, community groups, diabetes organisations, professional bodies, researchers, industry all being clear and consistent about the ask. Simple and effective communication about the issue is needed. Community drives the momentum – it always does and recognising that is essential. Using evidence to support why AID must be available to all with T1D is important, and goes perfectly with sharing examples of lived experience to highlight the benefit of the technology. Hearts and minds.

With the push already well established and a number of people powering the charge, it’s inevitable that the diabetes world in Australia is going to be hearing a lot about equitable AID and pump access in coming months. Keep an eye out on community groups for grassroots efforts to elevate the issue and for calls to get involved. We know that we can get this done – just as with getting CGMs funded for all people with T1D, for finding a novel way for Omnipod to be funded, and for Fiasp remaining on the PBS. (And, if we look further back, for getting pump consumables on the NDSS.)

Community will be critical to getting this across the line. Once again, we’ll need people with diabetes to step up and write letters, meet with local MPs, make noise, and show why this is necessary. Every single person with T1D and their families has a role to play here. If you’re already fortunate to be using AID, meet with your local MP and tell them how it has changed your life. If you haven’t had access, write about why you know it will help. For me, I’ll be talking about how much time I have grasped back not needing to do diabetes, how I have far fewer hypos, how I have an A1c in the ‘non-diabetes’ range which evidence suggests reduces my risk of developing costly complications. But most importantly, it has reduced my diabetes burden so much and that makes me a far happier, more productive person. And I want that for everyone with T1 D.

Postscript: a quick word (or two) about language. Media reports, especially in the UK, have incorrectly referred to the technology as an ‘artificial pancreas’. What we are talking about is automated insulin delivery devices (or hybrid closed loop systems). It’s important to get the language right for a couple of reasons: Artificial pancreas is simply not the correct term for what the technology is. It overstates what it does and potentially leads people to think the technology is a cure for T1D. Additionally, it underestimates the work that PWD do to drive the technology. More detail about why getting the terminology right is important can be found in this piece I wrote back in 2015 about the same issue and then again here from almost exactly two years ago.)

I’m introduced most generously by Adrian Sanders, Secretary General of the Parliamentarians for Diabetes Global Network.

Australian airports seem to have become a battleground recently for travellers with diabetes. My own experiences since Australia opened back up to travel have been appalling and each week there are reports in online diabetes pages about some pretty horrendous experiences. Specifically, the problems are to do with full body scanners which have been rolled out across international security checkpoints nationally, and some domestic checkpoints.

This year alone in half a dozen international flights out of Melbourne Airports and a dozen or so domestic flights, all been much more difficult than any travel experience pre-COVID. I documented one particularly brutal encounter at Brisbane Airport last year in this Twitter thread. Sadly, since then, other instances have been just as awful.

It seems that the training modules for security staff have incorrect information about which scanning devices are safe for diabetes devices. In my experience, the messaging is consistent: staff have been told that the metal detectors (the older walk-through screeners) are unsafe while the newer full body scanners (the stand still and be scanned) are safe. This is at odds with information from device companies and health professionals and has resulted in a number of people reporting clashes at security checkpoints.

There’s so much discussion about this, as well as lots of confusion and some pretty dire misinformation across OzDOC socials, some of it coming from diabetes groups. Let me try to break this down with information that is based on advice from device companies and the Department of Home Affairs. This is what I have used to try to help me streamline my own travel experiences – with varying levels of success.

Firstly, let’s start with the Department of Home Affairs. This page has the information you need, but specifically, under the section Travellers who have a mobility aid, prosthetic, medical device or medical equipment is this: ‘If you have a medical device or medical equipment, it may streamline the screening process if you have a letter or medical identification card from your doctor or healthcare professional that describes the device or equipment. It is also recommended that you talk with your doctor, healthcare professional or check the manufacturer instructions for guidance on whether the medical device or equipment is suitable for screening by body scanner technology or X-ray technology, and if not, make the screening officer aware of any restrictions before beginning the screening process.’

Device companies all have their own advice, so familiarise yourself with what their recommendations. I wear a Dexcom, and carry a printed copy of security screening advice. At the end of this post you’ll find links and relevant information about the different devices available in Australia.

Knowing how tricky things are likely to be, I am super prepared for security checks now. I carry a letter from my endocrinologist that states I’m wearing diabetes devices that must not go through the full body scanner, and that my pump cannot be removed (not so relevant these days as I wear Omnipod). In a sign of just how much the times have changed, I now need to show that letter about 80% of the time at Australian airports. Pre-COVID I maybe needed to produce it twice in hundreds of journeys.

I always remain calm and clear about what I need: ‘I am wearing medical devices and cannot go through the fully body scanner. I can go through the metal detector, or I need a pat down. I’m happy to wait out of your way.’ I stand firm with this request, remaining polite and calm even when there is increasingly aggressive pushback. In most cases, security staff will tell me that the training says body scanners are safe and metal detectors are not. At this point, I offer the letter from my doctor and the printed out advice from Dexcom and mention the relevant information from the Department of Home Affairs. If there continues to be pushback, I’ll ask to speak with a supervisor. I truly hate doing this.

While this isn’t applicable to me now, at no point ever would I remove my insulin pump and hand it to security staff for inspection. Disappointingly, some of the device companies’ travel advice (and today I saw advice from a diabetes centre) suggests this. Don’t do it. I am happy for them to swab it while I hold it, but I won’t disconnect and hand it over. Items go missing and handed to the wrong person or could be damaged at busy security checkpoints.

I know others with diabetes are happy to go through whatever scanner they are directed to and have had no adverse issues and that’s great. But this isn’t about individual experiences so much as about how to manage situations according to manufacturers’ advice and knowing what official information from the relevant Government department is. It’s also about being treated respectfully and having our own lived experience and knowledge respected by security staff; something that sadly seems to be repeatedly forgotten.

If you’ve had a lousy experience and have the emotional labour to write a complaint to the airport, please do so. There are online forms you can use.

It would be really great if this additional work didn’t fall to people with diabetes. Device companies could step up here and provide cards to use at security checkpoints, similar to those that have been developed for people with pacemakers and knee and hip replacements. Simultaneously it would be great if there was a form that could be personalised and printed out or a card issued via the NDSS when people register for pump and/or CGM access (this wouldn’t serve people who are self-funding, but it would reach the majority of Australians affected). While I am sure that there are efforts underway to address it, there’s no time to wait and a temporary fix is needed immediately. And any other advocacy groups who are addressing this issue can make sure that the advice they are providing on behalf of their diabetes community is accurate and best serves the needs of people with diabetes.

Advice from device companies in Australia

AMSL has this advice for Dexcom users: ‘Use of AIT body scanners has not been studied and therefore Dexcom recommend hand-wanding or full- body pat down and visual inspection in those situations.’

Insulet Australia has this advice for Omnipod users: ‘The Omnipod DASH® PDM and Pods are safe to go through the x-ray machine and the Pods are safe to be worn through airport scanners.’

AMSL has this advice for Tandem T:Slim users: ‘your Tandem Diabetes Care insulin pump should NOT be put through machines that use X-rays, including airline luggage X-ray machines and full-body scanners.

Medtronic has this advice: ‘Your pump should not go through the x-ray machine that is used for carry on or checked luggage or the full body scanner.’

Abbott has this information for FreeStyle Libre wearers: ‘The FreeStyle Libre reader and the FreeStyle Libre sensor can be exposed to common electrostatic (ESD) and electromagnetic interference (EMI), including airport metal detectors. You can keep your FreeStyle Libre sensor on while going through these. However, the FreeStyle Libre reader and the FreeStyle Libre sensor should not be exposed to some airport full body scanners.’

Because our little diabetes community is about sharing and caring, a sharing and caring friend of mine gave me a few Omnipod Dash pods to try. I’ve been Open-Source looping with an old (small size) Medtronic for the last 6 years, and the recent news that the 1.8ml cartridges were coming off the market sent me into a spin of despair. I probably wailed ‘Why do things keep changing?’ at some point.

I am firmly of the ‘If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it’ school of thought, and needing to re-evaluate my current, very-not-broke Medtronic Loop set up was not something I was particularly keen to do. But it seemed that the decision was being made for me, and switching to Omnipod seemed to be a not-too-stressful way to keep using Loop.

Of course, between my panic, wailing and fury (alongside talking myself off the ledge of stockpiling every box of 1.8ml Medtronic cartridges available in Australia), a DIY fix was already being created that involved cutting down the larger 3.0ml cartridges to safely fit the smaller pump.

But the seed had been planted. Maybe Omnipod could be the easy solution. Pods are easily available. I have private health insurance that hasn’t been used to get a pump since 2013. And, most importantly, I won’t need to stop using Loop, or lose any of the beautiful ease it has brought into my life. This has been the reason I’ve not switched to a commercial system. I’m not willing to consider anything that requires what I consider to be a step back. Not being able to bolus from my phone or smart watch, needing to carry another device to drive whatever I’m using, and less customisation are all a step back in my mind.

So, I bribed my sharing and caring friend with lunch, and he came over my way to deliver some pods for me to try and since then I’ve been on and off Omnipod since the beginning of August, including for ten days travelling in India for work.

I’ve been pumping for over twenty-two and a half years. I’ve never taken a pump break. When I say having an insulin pump hanging from my body is my normal, I mean it. It was with me in the delivery room when my kid was born and has travelled the world with me. I have worked out how to tuck a tubed pump away in my clothes so that it doesn’t cause any sort of unsightly bump and other than my constant (sadly losing) battle with door handles, the tubing really hasn’t bothered me.

For these reasons, I’d never understood the deep-seated position some people hold at not wanting to use a tethered pump, or the overall appeal of a patch pump. That’s not to say that I don’t think they’re a good option. I just wasn’t drawn to one the way that I know others have been. To be honest, I’ve been kind of ambivalent about the benefits of no-tubing. That was all 15 pods ago ago, and now I get it.

Here are some of the thoughts I’ve had since using Omnipod:

⊙ Oh my Lordy! Phantom-pump is a real thing. I spent the first week of wearing a pod groping around for my old Medtronic pump. I’d go to grab my pump if I got up out of bed overnight, or first thing in the morning. One night, I thought I’d ripped out my pump and after groping around for a few minutes, woke Aaron, thinking it was under him. Half asleep, he said ‘It’s on your arm.’ I still do ‘the pat down’ before walking out of the house each day, gently tapping the middle of my chest to reassure myself that my pump is there. It’s redundant these days!

⊙ I don’t know why I thought it might be more complicated to use than it is, but I was really pleasantly surprised by ease of it all. The clunk of the cannula going in is slightly startling the first time, (but no more so than putting in a sensor). I’ve not found it painful at all.

⊙ That tape sticks! After three days, the tape has still been firmly adhered to my skin and looking pretty pristine. This was even in India where it was hot and humid. This bodes very well for the warm Aussie summer we’re being promised!

⊙ I thought that the Pod would feel more obtrusive on my body, but I have absolutely not once had a moment of ‘Ooh – that’s uncomfortable’ when I’ve rolled over in bed.

⊙ I’ve worn the pod on my right arm (Dex is always on my left), sides of my stomach (low and high), thighs (and didn’t rip it off when pulling down my jeans to race to the loo!), hips, lower back and all have been fine. No pain or discomfort at all.

⊙ Not needing to wear a bra if I don’t want to is liberating! Not needing to consider housing my pump and Orange Link is one fewer thing to think about!

⊙ I feel lighter because there is one fewer pieces of diabetes kit I need to worry about now that my Orange Link is redundant. This is a big win!

⊙ I’ve had two faulty pods which isn’t great really and the ‘replace pod’ alert came after three hours of inexplicable high glucose levels that were not responding to adjustment boluses. I’d really like to know if a problem is detected with the device before three hours of low teens numbers. The two faulty pods have happened in the last four days and I’m actually back on my Medtronic right now because I am a little thrown right now, but I’ll go back onto a pod later in the week when I head to Sydney for work.

⊙ Sorting our replacements with customer service has been a slight rigamarole, requiring far more calls and questions than seem necessary, and requiring a lot more emotional labour that, quite frankly, I don’t have to give.

⊙ Door handles are friends again. (Door jambs on the other hand, are now potentially double trouble if wearing a Pod on one arm and Dex on the other!)

⊙ I don’t love the waste and the thought that I am effectively using a pump every three days. Insulet offers a super neat recycling program which goes someway to alleviating my concerns about this. I love that my delivery came with a labelled box, zip log bag and clear instructions for the recycling program. This is outstanding and I wish other device companies could be this forward thinking.

⊙ The three-day hard cut off annoys the crap out of me. And yes, I’ve been using the 8-hour grace period every single time. I know that we are meant to change cannulas (tubed or otherwise) every three days, but many of us extend by a day or two when we know it’s safe to do so. And twenty-two years of pumping, not a single site infection, and knowing when I’ve extended to my limit would suggest that I am able to safely decide to keep a pump running for a few more hours without having it screaming incessantly at me. Alas, that’s not possible here. (And how has the DIY community not figured a work around this yet??)

⊙ Cost is, of course a consideration. I’ve not used my health insurance yet, so I have paid the NDSS + Insulet cost which is $29.30 (NDSS cost) + $168.27 (Insulet cost) per box. It works out to just under $20 per pod which is not cheap. If I make the decision to use my private health insurance and start using Omnipod on an ongoing basis, I will only have the NDSS contribution, bringing the cost down to $2.93 per pod – way nicer!

⊙ Omnipod currently has a new user deal on. You get 90 days of Omnipod for $149.40. Really annoyingly this is only available to new customers. I tried to see if I was eligible for this (after all, I’d consider having bought only one box would classify me as ‘new’ to Omnipod, but alas, I was not eligible). This is actually very disappointing. I’ll never understand why companies ‘punish’ their existing customers. But, if you’re brand new to Omnipod, this is a great deal and I’d encourage you to get onto it now! It’s a great way to try before you commit to using your PHI.

⊙ The best thing? Choice! Having a tubeless pump available here in Australia means Aussies with type 1 diabetes have another pump choice and that is only ever a good thing and should be celebrated. I now get why people are determined to only use a tubeless pump and if that is their choice, it should be available to them, and they should be supported to make that choice. I’m hearing that there are some centres that won’t use Omnipod and that’s absolutely not okay. If anyone is in that situation right now, reach out if you’d like some suggestions about advocacy to change the situation.

It’s exciting to try new things and this really is the first significant diabetes device change for me in some time. It is energising to have something different to play with. If you’ve been thinking of trying something new, this is a good thing to try!

DISCLOSURE

None! I was given a few pods to try from a community member (who has no affiliation with Insulet or Omnipod) and bought a box myself. I have done some consulting work with Insulet before, but not in the last two years.