You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Diabetes’ category.

Eleven years ago on Mother’s Day, my friend Kerry started something on her socials. Kerry’s mum sadly died when Kerry was just six years old. She doesn’t have a single clear photo of the two of them together. And so, Kerry has urged her mum friends to make sure they take a photo with their kids – a really simple and special way to make sure that memories are recorded. (You can search for #KTPhotoForMum to see some lovely shared posts.)

We’re not short of photos in our household – who is in the age of smart phones? – but I especially love the album that I have of Mother’s Day photos of me and our girl. Seeing her on this day for the last eleven years brings a special feeling of joy.

But there’s another feeling in there that I want to recognise, and that’s how proud I am. Of course I’m proud of her – she’s a marvel (excuse my bias). But I’m talking about hoe I feel about myself as a mother living with diabetes. Because pregnancy and parenting with diabetes is not an easy gig.

I struggle with this sometimes. I don’t want to be defined by being someone’s mum. I achieved a lot before I became a mother and have done plenty in the last (almost) 20 years that I am so very proud of. There’s travel and a career, and media work, lots of published writing and a whole lot of standing on stages talking diabetes advocacy. These are usually the things that I point to when thinking about my achievements. For some reason, I’ve felt it’s diminishing to point to motherhood as an achievement.

But the truth is, that motherhood with diabetes is an achievement and it is defining in some ways. Conceiving, growing a baby, bringing her into this world, and getting her to adulthood is something that carries a huge sense of pride. Because, damn, diabetes made that hard. Every stage of it.

I get it: pregnancy is natural and it’s been happening forever and there are bazillions of people who have done it for a bazillion years, but there is absolutely nothing natural about taking on the role of a human organ. Seriously! It’s hard at the best of times. Being pregnant adds a degree of difficulty that is incomprehensible until you’re in the midst of it. Even today with tools that are far more sophisticated than the basic pump that saw me through my pregnancy, it’s still not easy. (And I utterly recognise how lucky I was at the time having a pump. The women sitting next to me at the Women’s Hospital diabetes & pregnancy clinic on Wednesday mornings who weren’t using a pump were real magicians.)

At that time I was just so in the weeds of dealing with all that came with a diabetes-complicated pregnancy that I never thought what an incredible job I was doing just getting through it. After all when was I meant to cheer myself for the remarkable effort? Was it before or after the 20+ finger prick checks I was doing each day? (CGM wasn’t around then.) Or alongside the complex calculations that I needed to complete before pre-bolusing the right amount of insulin at the exact right time? It certainly wouldn’t have been during the thirty percent of the day I was below target because in those moments, I was too busy worrying about starving my brain (and baby) of oxygen.

And then there was no time after she came along, because babies are all encompassing and take up every moment of the day. And diabetes can also be all encompassing and is incredibly demanding.

I had no time to be a cheerleader for myself because every single part of me was focused on making sure my baby’s elbows were growing properly, and stressing about how any out of range glucose level was harming her growing organs. Any spare brain bandwidth was taken up feeling guilty because I never felt I was doing enough. I felt that I was probably already failing my child. Even though her elbows are beautiful (and her organs seem fine), I still carry that guilt. Almost twenty years later.

These days, as more people with diabetes share their pregnancy and parenting stories, I DO cheer. Every time I hear about chaotic first trimester hypos, and managing glucose levels around second trimester cravings, and third trimester insulin-resistance frustrations, I know they deserve a loud ‘Hurrah!’ and so I cheer. Because look at these amazing people! Look at what they are doing – the work, the emotional rollercoaster, the determined effort they are putting in to keep themselves and their baby safe! Diabetes never plays nice, and for so many, pregnancy is the most difficult time in someone’s diabetes life.

Yesterday morning, I looked at our daughter as we had our Mother’s Day breakfast in the sunshine. Having her is the hardest thing I have ever done – the hardest, the most emotionally challenging, the scariest – but also the absolute best and I am so very proud that I did.

This post is dedicated to my dear friend Kati who I am cheering for every day!

Is there no limit to what people will blame on diabetes?? Because apparently now it’s being blamed for the death of a woman after she was violently assaulted.

Emma Bates, a 49 year old woman from Cobram (a country town in Victoria) was found dead in her home on Tuesday. She had serious injuries to her head and upper body after being allegedly bashed by a neighbour.

Friends and family have spoken about Emma and in their tributes, we learnt that she loved cats and was always helping people in her community. She had six siblings and was affectionately known in her family as the ‘crazy cat lady aunt’. It’s important to think about these sorts of things, because while we’re Counting Dead Women in Australia it’s far too easy to get lost in the horror of a rapidly increasing number, and stop centring the women behind each and every one of those numbers.

Emma also happened to live with type 1 diabetes. And because she lived with type 1 diabetes, the man who allegedly assaulted her has not been charged with manslaughter or murder because there’s uncertainty if it was the horrific injuries he’s been accused of inflicting or her diabetes that caused her death. His 13 charges include intentionally causing injury, recklessly causing injury, aggravated assault of a female and unlawful assault. This from an Australian newspaper:

‘… police told the family that murder or manslaughter charges were “off the table” after an early post-mortem examination was inconclusive about Bates’ cause of death.

She said the examination could not confirm whether Bates’ injuries caused her death, or whether her illnesses had played a part.’

Diabetes gets blamed for fucking everything.

Emma Bates. Say her name. Remember her name. She was one of us, one of our community. She lived with diabetes. And now it’s being used to diminish the severity of how her life ended.

There’s been a lot said about AID equity over the last few weeks. Actually, way longer than that. The momentum may have ramped up since a meeting at ATTD in Florence, but this has been something that the community has been speaking about for ages. In fact, I found a policy document advocating for pump access for all people with T1D from ten years ago, and I spoke at its launch in Parliament House . In there is a direct quote from me: ‘I decided to start using an insulin pump because my husband and I wanted to start a family. I knew of the importance of tight diabetes management prior to and during pregnancy. Insulin pump therapy gave me the ability to tailor and adapt my insulin doses to provide me with the best possible outcome – a beautiful healthy daughter.’

For the last six years I’ve been talking about how transformative AID has been with quotes like this: ‘Short of a cure, the holy grail for me in diabetes is each and every incremental step we take that means diabetes intrudes less in my life. I will acknowledge with gratitude and amazement and relief at how much less disturbance and interruption there is today, thanks to LOOP (AID).’

But enough from me. This is an issue that the T1D community owns and is engaged in. Last week at the #dedoc° symposium at the Diabetes UK Professional Conference, brilliant diabetes advocate Emma Doble spoke about patient and public involvement, highlighting how it refers to being with or by the community, not to, about or for them. The AID equity work underway is definitely with and by. It’s something community is calling for as a priority. A visit to any online T1D group will demonstrate that, and spending any time speaking directly with community will provide insight into the number of people who simply cannot access AID because they cannot afford an insulin pump. This is standard T1D care. The evidence is clear.

To get an idea of just how the T1D, and broader diabetes community feels, have a read of their own words. These comments are from the Make Automated Insulin Delivery affordable for all Australians with type 1 diabetes petition. They’re all publicly available, so you can click here to read the comments I’ve shared and many, many more.

‘Why would you bet against the type 1 community?’ That was a question asked in a session at the ISPAD conference a couple years ago. It wasn’t someone with T1D drawing attention to the community. Instead, it was said by someone working in global health who had seen the remarkable efforts such as the #WeAreNotWaiting movement and grassroots, peer-led education initiatives in low-income countries. These efforts have driven change and improved lives of people with diabetes. They have been led by those with lived experience and supported by other diabetes stakeholders. But the starting point is people directly affected by diabetes identifying a problem, solving it and leading the way. In the history of diabetes – from the first home glucose meters, to building systems leveraging off existing technologies, to global advocacy movements – community powered initiatives have been a driving force for change.

And so, here we are today, coming together once again to advocate for better equity and fairness for all people with type 1 diabetes, this time in Australia, and this time advancing access to automated insulin delivery devices (AID).

Insulin pump funding is broken. AID is standard care and yet far too many people are left unable to use the tech because of how pumps are funded in Australia. Right now, unless a person with T1D has the right level of private health insurance, or meets the criteria for the Insulin Pump Program, they must find the funding for an insulin pump. That needs to change.

We know how to do this in Australia. The reason that pump consumables are on the NDSS is thanks to community advocacy efforts back in the early 2000. And more recently massive community noise helped to get CGM onto the NDSS for all Australians. Of course, these wins worked because everyone was involved in advocacy: people with lived experience of diabetes, healthcare professionals and HCP professional groups, researchers, diabetes community groups and organisations and industry. What a lot of noise we can make when we’re singing from the same song sheet!

Right now, attentions are razor focused on improving access to automated insulin delivery systems because the evidence is clear: AID reduces diabetes distress, improves quality of life, and (for those who like numbers!), help with glucose levels. And as an added bonus for the bean counters – it’s a smart, cost-effective investment for our health system.

If AID is standard care, financial barriers preventing people from accessing it need to be eliminated.

And that’s where we would love your help.

Please sign and share the petition that has been started by Dr Ben Nash and supported by a group of people with T1D (including me). Petitions are a great way to get people talking and interested in a topic. It builds momentum and helps contribute to whole of community conversations. While we know the T1D community is already on board, we’ve now seen a number of HCPs, community groups and diabetes organisations share and promote the petition and are keen to get involved with broader advocacy efforts. That’s pretty cool!

Postscipt:

Understandably, there are questions about why this work is specific to T1D technology access. That’s a fair question and I think that our very own Bionic Wookiee provided an excellent explanation of that when he said this in a social media post earlier this week:

‘AID systems were developed for T1D (where they can track all the insulin going into the system without having to cope with the body’s variable insulin generation). So right now they mainly apply to T1D…

Expanding CGM and pump access to people with other forms of diabetes than just T1D is important for the future. Having wider access to AID for the T1D population will be a beach-head for that.‘

And in a conversation I had about this with UK diabetologist Partha Kar yesterday he cautions that there needs to be a starting point because the sheer numbers of diabetes can be daunting and tend to scare policy makers. He also points out that when it comes to outcome modifying interventions, technology is THE thing in T1D, whereas in other types of diabetes there are other options. I’ll add that those other options often have stronger evidence which is why they already have funding.

Anniversaries – diaversaries – are for remembering. And today, my twenty-sixth diaversary, I’ve remembered that diagnosis day, and a lot of what has happened since. I’ve had a sensor fail. I’ve also enjoyed doughnuts, coffee and sunshine, and an AID so smart it has cleaned up all my diabetes incompetence and delivered a day of 95% TIR. Measure for measure, it’s been a good day!

My life would be impossibly different today if diabetes hadn’t moved in all those years ago. So much of my life, and so many of the people in it, is because of diabetes. The utterly confused and terrified twenty-four year old woman who walked out of a GP appointment after a diagnosis of T1D would never have believed the turn my life would take after I fell head first, and completely accidentally, into a life of diabetes advocacy. She wouldn’t recognise who I am, or how I fill my days and the people alongside me, the never-ending decisions I am forced to make, or the ever increasing stamps in my passport. She wouldn’t understand the normal that is my every day. But in the same way, I don’t remember her normal. (And thanks to Effin’ Birds for so beautifully illustrating that for me…)

Diaversaries are for remembering, but they are also for looking forward. Advocacy features so overwhelmingly in my future (and my present – I’ve spent a day off today working on an Australian grassroots community campaign). And so does advocating beyond our borders with the global access work I am so honoured to do at JDRF. And that means looking forward to people with a shared vision for real community and community involvement in ways that are meaningful and impactful. When I think of the last twenty-six years, community and others with diabetes feature so strongly. Because community is everything.

But perhaps most of all, diaversaries are a good opportunity to be hopeful. Advocacy has shaped who I am and how I have lived with diabetes, but hope has too. It’s as much of a driving force as anything else, something I hold on to every single day. I’m hopeful that access to diabetes care, insulin and other meds and technology becomes more equitable and that the heavy burden of diabetes casts an ever-diminishing shadow.

Hasn’t it been terrific this week seeing a couple of great news stories in the T1D tech world? Our friends across the ditch in NZ have welcomed an announcement from medical regulatory board Pharmac that all people with type 1 diabetes will have access to CGM and automated insulin delivery devices (AID). Meanwhile, this week saw the start of a five-year national roll out of AID in England and Wales which recommends access be granted to children and adolescence (under 18 years) with T1D, pregnant people with T1D and adults with T1D with an A1c higher than 7%.

So, where is Australia when it comes to people with T1D being able to affordably access automated insulin delivery devices?

Let’s start by highlighting the positives. There’s so much to be grateful for here in Australia. The NDSS continues to be a shining light for Australians with diabetes. Syringes and pen tips are free at NDSS collection points and BGL strips are subsidised. Since 2004, insulin pump consumables have been on the NDSS, CGM sensors and transmitters have been subsidised since 2022. Insulin is heavily subsidised by the PBS.

But even with these benefits diabetes remains costly, and the playing field isn’t level. Pumps remain out of reach for many Australians. Without private health insurance or meeting eligibility to apply for the government funded Insulin Pump Program, people with T1D are required to find up to $10,000 for an insulin pump. That’s simply not affordable and it means that Australians with T1D can’t access AID.

With AID providing real life-changing benefits and significant reduction in diabetes burden, now is the time to ensure that the tech is available to everyone with T1D who wants it – not just those who can afford it. And that means that it’s time to equitably fund the missing piece of the AID puzzle: Pumps.

A fire has been lit. From a small meeting at ATTD in Florence to catch ups, coffees and phone calls back home, the groundswell has well and truly started. People with diabetes are central to this, working closely with motivated and determined HCPs and diabetes community organisations. There is a united focus on what needs to be done: affordable insulin pumps so AID is a reality for every Australian with type 1 diabetes who chooses. And excitedly, there seems to be an appetite for this from policy makers.

So what can we learn from the recent successes in NZ and the UK? Well, it’s exactly what we know from our previous advocacy experiences and wins here in Australia. A united stakeholder approach is critical with everyone from individuals with diabetes, community groups, diabetes organisations, professional bodies, researchers, industry all being clear and consistent about the ask. Simple and effective communication about the issue is needed. Community drives the momentum – it always does and recognising that is essential. Using evidence to support why AID must be available to all with T1D is important, and goes perfectly with sharing examples of lived experience to highlight the benefit of the technology. Hearts and minds.

With the push already well established and a number of people powering the charge, it’s inevitable that the diabetes world in Australia is going to be hearing a lot about equitable AID and pump access in coming months. Keep an eye out on community groups for grassroots efforts to elevate the issue and for calls to get involved. We know that we can get this done – just as with getting CGMs funded for all people with T1D, for finding a novel way for Omnipod to be funded, and for Fiasp remaining on the PBS. (And, if we look further back, for getting pump consumables on the NDSS.)

Community will be critical to getting this across the line. Once again, we’ll need people with diabetes to step up and write letters, meet with local MPs, make noise, and show why this is necessary. Every single person with T1D and their families has a role to play here. If you’re already fortunate to be using AID, meet with your local MP and tell them how it has changed your life. If you haven’t had access, write about why you know it will help. For me, I’ll be talking about how much time I have grasped back not needing to do diabetes, how I have far fewer hypos, how I have an A1c in the ‘non-diabetes’ range which evidence suggests reduces my risk of developing costly complications. But most importantly, it has reduced my diabetes burden so much and that makes me a far happier, more productive person. And I want that for everyone with T1 D.

Postscript: a quick word (or two) about language. Media reports, especially in the UK, have incorrectly referred to the technology as an ‘artificial pancreas’. What we are talking about is automated insulin delivery devices (or hybrid closed loop systems). It’s important to get the language right for a couple of reasons: Artificial pancreas is simply not the correct term for what the technology is. It overstates what it does and potentially leads people to think the technology is a cure for T1D. Additionally, it underestimates the work that PWD do to drive the technology. More detail about why getting the terminology right is important can be found in this piece I wrote back in 2015 about the same issue and then again here from almost exactly two years ago.)

I’m introduced most generously by Adrian Sanders, Secretary General of the Parliamentarians for Diabetes Global Network.

The #dedoc° symposium kicked off ATTD 2024 in the most powerful way. Four community advocates from across the globe presented on a variety of topics including access to insulin during humanitarian crises, access to diabetes care and technologies in low income settings, accessibility of technology for people with diabetes also living with disabilities, and access to research findings. You can hear the brilliant talks from #dedoc voices Leon Tribe, Tinotenda Dzitiki, NurAkca and Asra Ahmed here.

During the panel discussion, there was an important discussion about how and why it is critical for people with diabetes to be included in all conversations about diabetes. Meaningful consultation is the golden ticket here, and there were some valuable comments and suggestions about how that happens. Someone asked the question about reimbursement for lived experience expertise, an often ignored issue when it comes to people with diabetes being involved in research, programs, committees and anything else that takes our time. Our unique perspective cannot be provided by anyone else, and yet there is rarely budget to cover the costs of our participation. Sadly, it’s not routine to offer payment for our time, instead we are often made to feel that we should be grateful for a seat at the table. It’s worth reminding those who don’t value us in a financial way that WE ARE THE TABLE and without us, there wouldn’t be a place setting for anyone else.

It was clear from the conversation that diabetes advocates – even those sitting on stage at International scientific conferences – find it difficult to ask for their valuable expertise and time to be reimbursed.

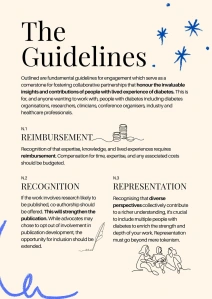

I jumped off stage and made a bee line for Jazz Sethi. We do this thing at conferences that I’ve started referring to as the ‘Jazz and Renz conference special’. (You can see previous efforts here and here.) Within five minutes we’d hatched a plan for our next project, and today, we’re so excited to share it. It was clear that we need some ‘Rules of Engagement’ that provided a clear and easy way for people with diabetes and those seeking to work with us to understand not only why engagement and consultation is essential, but why it’s also essential to pay for our time.

It’s not just about reimbursement though. It’s also about recognition for that work in a multitude of ways including being included as a co-author on publications, included on programs giving presentations and having our expertise acknowledged as just as important as all other diabetes stakeholders.

And so, here are some simple guidelines that can be used by people with diabetes when working with organisations, researchers, healthcare professionals, industry and anyone else who wants out expert knowledge. Use them in your discussions with anyone who invites you to be involved in diabetes work. Print them out and take them with you when you’re meeting with anyone running a project or convening an advisory group. Share them in your networks so as many people as possible can use the information to guide discussions about ensuring our value is truly acknowledged. We hope that this will make those discussions just a little easier.

And for those who wish to work with us, have a read. If you still think that our time isn’t worth your budget, or our expertise worth real recognition, then it can only be considered that you are doing the very least to include people with diabetes. That’s tokenism. We’re not here for that anymore.

Disclosure

I was an invited speaker at ATTD 2024 where I presented on the T1D Index in my capacity as Director Community Engagement and Communications in the Global Access Team at JDRF International. I also chaired a session on access to research. ATTD covered my registration costs. My travel and accommodation were covered by #dedoc° where I am Global Head of Advocacy. I chaired the #dedoc° symposium at the conference.

I stumbled across a book the other day called Women Holding Things. The author and illustrator, Maira Kalman referred to it as ‘love song to those exhausted from holding everything’. It’s quite gorgeous, with beautiful illustrations of all the things women hold – both literally and figuratively.

And I thought about what people with diabetes hold and just how weary and drained the weight of carrying diabetes and all that comes with it can be. I can’t draw, but here are my words that highlight some of the things we hold. It’s a love letter to the strength people with diabetes have gained through holding things, even when we want nothing more than to put it all down.

We hold on because we have no other choice but to do so.

We hold bags carrying around diabetes supplies – right now as I wait to board a flight, I have a separate bag with nothing more than sensors and pumps and alcohol wipes and spares of everything. I will hold it through airports, as I climb on planes, on ground transfer to hotels, and around with me through every step of my journey, a constant companion in my travels.

We hold cups of coffee because sometimes it feels like the only thing that will get us through the day.

We hold a fear of the future and what it can be, a shadow that sometimes stretches longer than we’d like.

We hold emergency hypo snacks ready for those unexpected moments. Or expected… (see: airports).

We hold guilt for some ridiculous reason because we shouldn’t and it is heavy and we would be so much lighter if we could let it go. But it’s there. We hold it.

We hold hope so close to our hearts, trying to balance up the fear or at least make a dent in its weight.

We hold insulin bottles and glucose monitoring supplies and all the little things that are needed to be replacement pancreases.

We hold anxiety and worry, and at times, a quiet uncertainty about what the next day, the next week, the next year holds.

We hold our diabetes friends close because they understand without needing explanations, and we hope that by being there for them as they hold us close, somehow there is a magic law of reciprocity that means we’re all holding less a little less diabetes.

We hold other diabetes stakeholders to account when they fall short of our expectations or fail to understand the nuances of our lived experiences, or underestimate our expertise. Or when they unleash a campaign that instils more fear.

We hold a steady gaze at research to see what our future life with diabetes might hold.

And we hold onto the promises, even the five-more-years promise that we know is a joke, but perhaps, just perhaps if we hold onto it tightly it might, it just might come true.

We hold our heads high as we advocate for better care, more understanding, and greater awareness.

We hold bottles of cinnamon, not because we know it’s a cure, but because it tastes great in the apple cake we’re holding onto for afternoon tea.

For those of us who can remember a before time, we hold on to memories about what life was like before we had to hold onto and carry diabetes.

We hold the hands of those whose diagnosis came after ours because we’re so grateful to those who came before us and held our hands.

We hold the key to lived experience and with it, we hold a unique perspective that must be listened to. Because we hold onto the belief that #NothingAboutUsWithoutUs

We hold a wealth of knowledge that comes from being a world class expert in our diabetes.

We hold a firm grip on the reality of life with diabetes because if we let that slip the consequences are too great to imagine.

We hold an inner strength that often surprises even ourselves.

Sometimes we hold back nothing as we tell our stories and and advocate for what is right.

We hold the power to change perceptions, influence policy, and inspire others.

We hold our spirits high when we feel we’ve had a win because holding onto those small victories carries us on through times where we feel we’re dropping the ball.

We hold our loved ones close, sometimes to protect them, sometimes to draw strength from their support.

We hold the courage to face each day, each challenge, with a bravery we often don’t credit ourselves for.

We hold a steady pace, because we know that diabetes is a marathon, not a sprint.

We hold onto the belief that it will be okay, that we will be okay. Because otherwise, there is nothing at all to hold onto. And that…that is just too heavy to contemplate.

The day after I was diagnosed with diabetes, I found myself in floods of tears, sitting in the stairwell of the Diabetes Victoria offices on Collins Street in Melbourne. I’d fled there from the NDSS shop that was housed on level three after suddenly feeling overwhelmed at the boxes and boxes of curious looking diabetes supplies that were about to be sent home with me. I was slumped against the wall, the emotion of the last twenty-four hours catching up with me. Someone came down the stairs and stopped. She crouched down and quietly said. ‘Hi. Are you okay?’

I wasn’t. Of course I wasn’t. ‘Can I sit here for a minute?’ she asked and somehow, through the tears, I nodded.

As it turned out, she was a diabetes educator working at Diabetes Victoria. And she also had type 1 diabetes. She spoke, I listened. And listened and listened. It was the first time I heard another person with diabetes share her experiences. She told me she too felt overwhelmed at times. And, she told me that right now – so new to it all – it feels so big, and that is perfectly understandable. She assured me that it would feel less big. She told me about bits of her life with diabetes and while she didn’t make it sound like bowls of cherries and puppy dogs, she took away tiny bit of the diagnosis fear that punches you right in the heart. Her stories made no sense at the time, but, as my own diabetes story grew, bit by bit, I understood her experiences.

I continue to search for stories today. I share some of mine – the things I feel comfortable sharing. And sometimes the things that aren’t all that comfortable.

I’m eternally grateful to that diabetes educator I met on 16 April, 1998. I told her repeatedly that her kind reassurance was the only brightness in those dark couple of days. I’m grateful to every other person who has so generously shared their lived experience. I never take it for granted – especially the reliving the trauma of difficult times.

And so tell your story. Only if you want.