You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Real life’ category.

It’s RUOK? day and while I am ready to jump on any worthwhile bandwagon, this one, today, seems especially important. A (non-diabetes) community of which I am on the periphery is grieving today after the death of a much-loved friend and colleague. I’ve been reading beautiful tributes to this person and messages of love and support to their family. I can’t begin to grasp what their loved ones are going through today.

RUOK? is more than a single day. It’s a movement that emphasises the power of human and social connection and having conversations about difficult things. If you’ve not looked at the website, there is advice about building the capacity of support networks (the very foundations of diabetes peer support groups for decades now) and developing skills to have meaningful discussions with someone who might be struggling.

It’s applicable to everyone, including those who may appear to not necessarily need it. Undeniably, it’s very relevant to diabetes. (This article outlines the increased risk of suicide in people with diabetes.)

Diabetes and mental health may be a topic on the agenda at most conferences and we’ve certainly seen an uptick in mental health and diabetes research over the last decade. But the strides that have been made are not enough. The pathway to genuine support and treatment for people with diabetes remains elusive. Simply telling people to seek help falls short when the help they need is not available.

Our peer networks go a long way to offering support, empathy, and love, but we’re not equipped to handle complex mental health issues. While we can assure people that they are not alone and perhaps offer suggestions for where they may find help, this does not go far enough in addressing mental health care, especially in critical situations. Accessing mental health professionals that have knowledge and training to support people with diabetes is what is needed. And it needs to be easily accessible. Easily affordable. Easily available. Right now, that’s not the case.

On RUOK? Day implores us to tap into our social circles and genuinely check in. (Do it, please; just do it). But there is a braider landscape of mental health in the diabetes landscape that needs real transformation. And while it seems unreasonable to add extra burden to those of us living with diabetes – after all, we are already expected to do so much of the physical, emotional, social, and political labour just to get by – community action drives change so often. We have had successful and coordinated community efforts to increase technology funding and access. Is our next frontier turning our attention to increasing funding and access to mental health care for people with diabetes? I know that some diabetes organisations have this in their sights, but without people with diabetes making noise, the campaign is only half-baked. Our voices amplify the urgency of the issue.

Today is just one day, but if RUOK? Day is what provides the gentle nudge to initiate these conversations, it’s a step forward. The tapestry of personal narratives, community connections and shared experiences form the basis of peer support. But not everyone has a safe space where they can share or the people to share with. Sometimes we need to reach out, extend a hand and signal we’re ready to listen. Keep reaching out. Today. And tomorrow. Every time you can.

There are moments when someone says something so illuminating that it sticks with me and I turn their words over and over and each time, those words hit home deeper and deeper.

That’s how I’ve been since last week, when Victor Montori, during his talk at the Nossal Institute for Global Health’s Compassion, Care, Complexity & Culture webinar said: ‘The work of being a patient is invisible‘. He went on to talk about just some of what is required of people living with health conditions. Of course, Victor is spot on! There is nothing simple about needing to navigate complex health settings and systems, yet most of our work to make it all make sense is not seen or recognised.

As soon as he said it, I realised that those of us with diabetes are hit with a double whammy. Not only is the work we do invisible, but so is our health condition. We don’t ‘look sick’. There is often very little to point to our diabetes and how it can challenge, frustrate, exhaust us. I frequently talk about what it takes to ‘do diabetes’ – the arduous, momentous, all encompassing tasks that it relentlessly demands of us. But how many people actually see that? Diabetes isn’t alone here; there are certainly other invisible conditions.

We need to exist and function within health systems that sometimes feel as thought they are working against us and as health becomes more and more corporatised, our frustrations grow. Perhaps it’s just me, but with every mission statement and strategic plan that promises to do better by people (with diabetes or whatever), all I seem to see is less recognition of what real life for us is like. My consulting side hustle often has me being asked to review these documents, and the question I ask most is ‘And what does this mean exactly for the people you are meant to be serving? How exactly are you going to reduce the burden?’ (or whatever it is that they have promised to do). In most cases they can’t answer and furthermore, there is a genuine lack of understanding of what that burden is.

Is making the work of being a ‘patient’ more visible to more people what is required to systems to change? I know that in the case of diabetes, it is those health professionals who recognise what we do to make our invisible condition tick are the ones who are often more generous in their dealings with us. My endocrinologist has frequently acknowledged just how much there is to do with diabetes, how hard it is, and understands that no one really wants to have to do it. She’s right. On all counts. But I wonder how she knows that when so many others simply don’t.

We regularly hear about how overworked healthcare professionals are and how our under-resourced health systems are working to capacity and I don’t for a moment doubt any of that. But you know who else is working to capacity? Those of us living with health conditions. But for us, looking after our health is a burden on top of ‘every day life’. It’s a job on top of our jobs. It’s just that we do it all hidden from plain sight.

The only way that the work we do will become visible is if we talk about it, and work to quantify it. Justin Walker’s comment at the DData event back in 2018 went some way to doing that when he said ‘By wearing OpenAPS, I save myself about an hour a day not doing diabetes‘. I can’t tell you the number of times I have quoted this because it shows two things: firstly, just how effective Open Source AID (and perhaps commercial systems too) can be at reducing the burden of diabetes tasks, and secondly, to highlight how much time those tasks take. Getting back an hour of my day, each day, has been brilliant. But there are still minutes lost every day to diabetes. And what we do during those minutes is largely unseen. It’s the invisible work Victor spoke of.

The invisible work extends to the hoops we need to jump through simply to exist. I hear from friends in the US the hours and hours of work they need to do to sort through health insurance issues. This week, I’ve spent hours upon hours of my time trying to navigate VicRoads (the state’s licensing authority) and the decision that, despite no changes to my diabetes, additional medical reports were necessary for me to keep my license. The final outcome was the sensible one – no need for anything further, after all – but it took emails, several phone calls where I was required to explain and explain and explain again, text messages to my endocrinologist, and my own inside-out knowledge of the guidelines before the right outcomes was reached.

I feel that as health system frequent flyers, we have simply come to expect that this is part and parcel of the process and I so appreciated Victor highlight the work, and suggest that the burden that has fallen to us should be remembered. I have thought about it a number of times since the event: after waiting for 45 minutes to see a nurse for a vaccine last week, only to be told the vaccine wasn’t in stock and I’d need to source it (even though I asked if it was available); as I raced between two different pharmacies to collect said vaccine after the one I called first didn’t have it available, despite them promising me they did just ten minutes earlier when I called, while listening to hold music as I waited for 15 minutes so I could speak with someone to reschedule a screening check that had been cancelled for no apparent reason, as I rearranged a meeting so that I could get to the local pathology centre for a fasting blood check (after being sent away the previous afternoon because I wasn’t aware that I needed to fast for that particular check). And while speaking to the third medical reviewer at VicRoads yesterday.

I don’t know anyone who wants to do the invisible work of being ‘a patient’. And yet, I feel that we all know that there isn’t a choice. We accept that the toils of managing diabetes persist, silently and profoundly hidden in the shadows. And feel locked into a contract that expects us to do hours and hours of work apparent to no one. Invisible, perhaps. But real? Absolutely.

On Sunday, one of those annoying diabetes things happened – a kinked insulin pump cannula, subsequent high glucose levels followed by a little glucose wrangling tango where, instead of rage blousing, I tried to gently guide my numbers back in-range. I thought about how frustrating diabetes can be – unfairly throwing curve balls at us even when we are doing ‘all the right things’. And so, I used this little story for a post on LinkedIn to illustrate why I am so dedicated to making sure that stories like this are heard and lived experience is centred in all diabetes conversations.

Meanwhile, anyone who has even the barest of little toes dipped in the water of the diabetes community would have heard about Alexander Zverev being told by French Open officials that he was not permitted to take his insulin on court. He was expected to inject off court and, according to Zverev, was told ‘looks weird when I [inject] on court’. Insulin breaks would be considered as toilet breaks.

What’s the connection between this story and my LinkedIn story? Absolutely none. Except there kind of is.

I’m not about to write about sports or try to connect my story with that of a top-ranking tennis player. That would be totally out of my lane. (The couple of years of tennis I took when I was in grades five and six give me no insight into life of a tennis player.)

However, when it comes to discussing diabetes and the stigma surrounding it, I’m definitely in my lane. I understand and am very well-versed when it comes to talking about the image problem diabetes faces and how that fuels the stigma fire.

The response from the diabetes community when the Zverev story broke. Most people were incredibly supportive of the tennis player and rightfully indignant of the incident. JDRF UK responded swiftly with an open letter to the French Open organisers, eloquently highlighting why their ruling needed to be changed. And changed it was.

My LinkedIn post was shared a few times and there were comments from people saying that these stories help others better understand our daily challenges and work to cut through a lot of the misconceptions about diabetes.

And then there was this direct message:

I bristled as I read it. My initial response was ‘How dare this man try to tell me what I can and can’t post on LinkedIn. Who is he to tell me what I can and can’t share?’ I snapped a reply back to him where I pointed out: ‘…I am a diabetes advocate, working to change attitudes and raise awareness about living with diabetes. My post belongs here on LinkedIn as it very much aligns with the work I do.’

But I haven’t been able to stop thinking about it because as problematic as it is for someone trying to silence what people with diabetes share online, there was more that was troubling me.

The idea that diabetes is a topic only appropriate in certain contexts and should be hidden away from others reinforces shame. Suggesting work settings are not the place to talk diabetes plants that seed that diabetes, and people with diabetes, could be liabilities in the workplace. Talking about diabetes on LinkedIn – a platform for business and workplace networking – is relevant because people with diabetes exist in business and workplaces, and the reality is that diabetes sometimes interferes with our work. Which is perfectly okay. Last week, I needed to refill my pump during a meeting. So, I let others on the call know what I was doing and carried on. On another day, I was recording a short video about a research program and after take 224 realised I needed to treat a hypo and did so. I shouldn’t need to feel that these aspects of daily life with diabetes are only allowed to happen out of view.

Essentially, this is what Alexander Zverev was being asked to do at his workplace: hide away when he needed to perform a task that keeps him alive, as if there is something shameful and disgusting about it. In my mind, this top ranked tennis player playing in a Grand Slam competition should be commended. I mean, any tennis player who does that is remarkable. Zverev does it and then goes about performing the duties of a pancreas. His opponents don’t have to do that! Their pancreas doses out the perfect amount of insulin without any help. Talk about an unfair advantage!

Not everyone wants to talk diabetes with others and that’s fine. But those of us who are happy to speak about and ‘do diabetes’ wherever we are shouldn’t feel that we are doing anything wrong. Diabetes stigma exists because there are so many wrong attitudes about diabetes. It’s insidious and it’s damaging. It erects barriers creating a climate of shame and perpetuates misconceptions that lead to ignorance. And it pressures us to hide away the realities of diabetes, as if there is something to be ashamed of. But there is nothing shameful about living with diabetes. There is nothing shameful about injecting insulin on Centre Court at Roland-Garros, or sharing frustrations on LinkedIn. Or anywhere else. Diabetes has a place wherever your workplace might be. Stigma, however, does not.

Twenty-five years of diabetes. You bet that’s worth celebrating.

And I did, spending a couple of hours at a local Italian pasticceria with gorgeous family and friends, eating our way though pastries and drinking copious quantities of coffee. Is there a more perfect way for me to celebrate a quarter of a century – and over half my life – dealing with diabetes? I think not!

This commemorative coin was given to me by Jeff Hitchcock from Children with Diabetes. This is the organisation’s Journey Awards’.* What a fabulous recognition of the hard slog that is day-to-day life with diabetes. Of course, here in Australia there are Kellion medals, but these are not awarded until someone has lived with diabetes for 50 years. I love the idea of acknowledging years of diabetes along the way to that milestone, and am extraordinarily grateful to have this one on my dresser at home.

Because really, there is much to celebrate. Getting through the good, the bad, the ugly, the frustrating, the humorous, the wins, the losses, the CGM flat lines, the CGM rollercoasters, the times we nail a pizza bolus, the times we totally botch a rice bolus, the times we exercise and don’t have a crashing hypo, the hypos from out of nowhere, the stubborn highs that make no sense, the visits to HCPs that feel celebratory, the visits that make us feel like crap, the fears of the future and the present, the tech that works, the tech that makes things more difficult, the stigma, the desperation of wishing diabetes away, the horrible news reports, the crappy campaigns that position diabetes negatively and those of us living with it as hopeless, the great campaigns that get it right, the allies cheering us on. All of these things – all of them – form part of the whole that is me and my life with diabetes.

Happy diaversary to me! And thank you to the people along for the ride. How lucky I am to have their love and support in my life.

As for diabetes. I still despise it intensely. I still wish for a life without it. I still believe I deserve a cure. At the very least, I deserve days where diabetes is less and less present.

I am so forever and ever hopeful for that.

More diaversary musings

*More details of CWD’s Journey Awards can be found here. Please note that they are only shipped to US addresses due to postage costs.

‘What would the ideal campaign about diabetes complications look like?’

What a loaded question, I thought. I was in a room full of creative consultants who wanted to have a chat with me about a new campaign they had been commissioned to develop. I felt like I was being interrogated. I was on one side of a huge table in a cavernous boardroom and opposite me, sat half a dozen consultants with digital notepads, dozens of questions, and eager, smiley looks on their faces. And very little idea of what living with diabetes is truly about, or just how fraught discussions about diabetes complications can be.

I sighed. I already had an idea of what their campaign would look like. I knew because more than two decades working as a diabetes advocate means I’ve seen a lot of it before.

‘Well,’ I started circling back to their question. ‘Probably nothing like what you have on those storyboards over there’. I indicated to the easels that had been placed around the room, each holding a covered-over poster. The huge smiles hardened a little.

Honestly, I have no idea why I get invited to these consultations. I make things very hard for the people on the other side of the table (or Zoom screen, or panel, or wherever these discussions take place).

I suppose I get brought in because I am known for being pretty direct and have lots of experience. And I don’t care about being popular or pleasing people. There is rarely ambiguity in my comments, and I can get to the crux of issue very quickly. Plus, consulting means getting paid by the hour and I can sum things up in minutes rather than an afternoon of workshops, and that means they get me in and out of the door without needing to feed me. I think the industry term for it is getting more bang for their buck.

I suggested that we start with a different question. And that question is this: ‘How do you feel when it is time for a diabetes complication screening’.

One of the consultants asked why that was a better question. I explained that it was important to understand just how people feel when it comes to discussions about complications and from there, learn how people feel when it’s time to be screened for them.

‘The two go hand in hand. I mean, if you are going to highlight the scary details of diabetes complications, surely you understand that will translate into people not necessarily rushing to find out more details.’

I told them the story I’ve told hundreds of times before – the story of my diagnosis and the images I was shown to convey all the terrible things that my life had in store now. Twenty-five years later, dozens and dozens of screening checks behind me, and no significant complication diagnosis to date, and yet, the anxiety I feel when I know it’s time for me to get my kidneys screened, or my eyes checked sends me into a spiral of fret and worry that hasn’t diminished at all over time. In fact, if anything, it has increased because of the way that we are reminded that the longer we have diabetes, the more likely we are to get complications. There is no good news here!

‘But people aren’t getting checked. They know they should, and they don’t. And some don’t know they need to. Or even that there are complications,’ came the reply from the other side of the table.

Now it was me whose face hardened.

‘Let’s unpack that for a moment,’ I said. ‘You have just made a very judgemental statement about people with diabetes. I don’t do judgement in diabetes, but if you want to lay blame, where should it lie? If you’re telling me that people don’t know they need to get checked or that there are diabetes complications, whose fault is that?’

I waited.

‘Blaming people or finding fault does nothing. That’s not going to help us here. You’ve been tasked to develop something that informs people with diabetes about complications – scary, terrifying, horrible, often painful – complications. Do you really want to open that discussion by blaming people?’

Yes, I know that not everyone with diabetes knows all about complications, and there genuinely are people out there who do not fully understand why screening is important, or what screening looks like. The spectrum of diabetes lived experience means there are people with a lot of knowledge and people with very little. But regardless of where people sit on that spectrum, complications must be spoken about with sensitivity and care.

The covers came off the posters around the room, and I was right. I’d seen it all before. There were stats showing rates of complications. More stats of how much complications cost. More stats of how many people are not getting screened for complications. More stats showing how complications can be prevented if only people got screened.

‘Thanks, I hate it,’ I thought to myself silently.

I spent the next half an hour tearing to shreds everything on those storyboards. We talked about putting humanity into the campaign and remembering that people with diabetes are already dealing with a whole lot, and adding worry and mental burden is not the way to go. I reminded them that telling us again and again and again, over and over and over the awful things that will happen to us is counterproductive. It doesn’t motivate us. It doesn’t encourage us to connect with our healthcare team. And it certainly doesn’t enamour us to whoever it is behind the campaign.

I wrapped my feedback in a bow and sent a summary email to the consultants the following day, emphatically pointing out that I am only one person with diabetes and that my comments shouldn’t be taken as gospel. Rather they should speak with lots of people with diabetes to get a sense of how many people feel. I urged them again to resist using scare tactics, or meaningless statistics. I reminded them that all aspects of the campaign – even those that might not be directed at people with diabetes – will be seen by us and we will be impacted by it. I asked that they centre people with diabetes in their work about diabetes.

But mostly, I reminded that anything to do with complications has real implications for people with diabetes. What may be a jaunt in the circus of media and PR for creative agencies is our real life. And our real life is not a media stunt.

Disclosure

I operate a freelance health consultancy. I was paid for this work because my expertise, just as the expertise of everyone with lived experience, is worth its weight in gold and we should be compensated (i.e. paid!) for it.

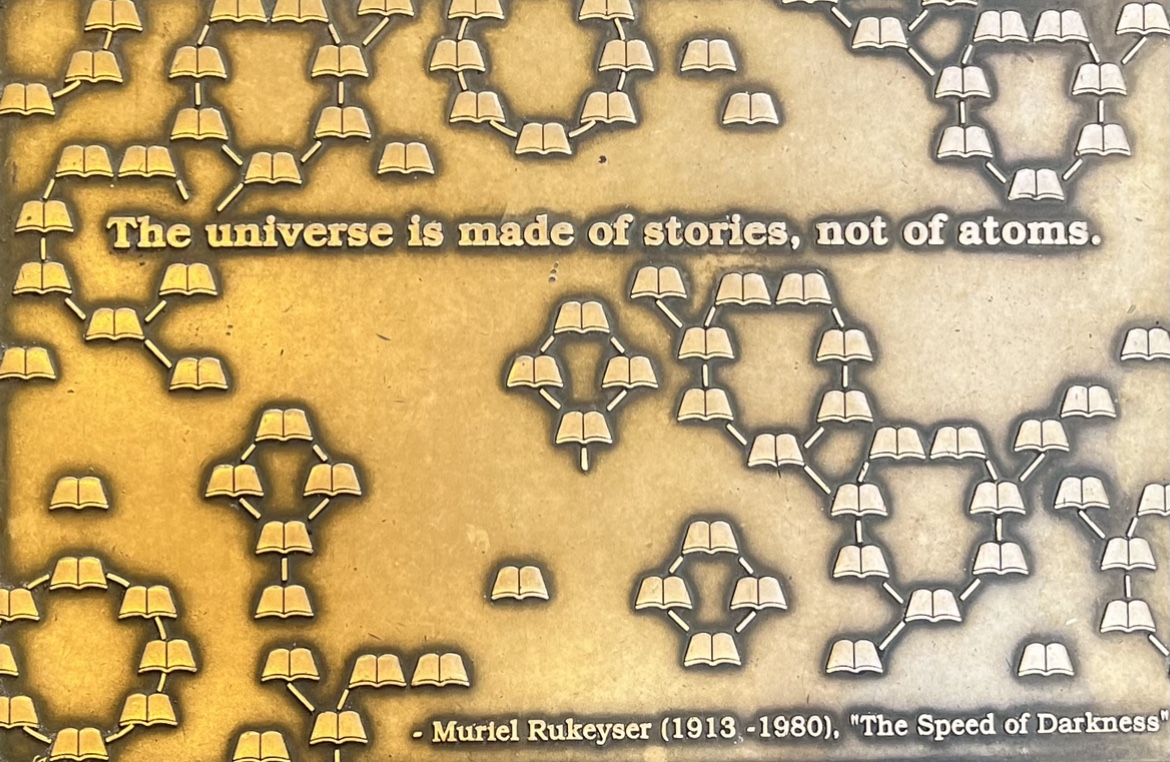

Manhattan’s East 41st Street is Library Way. Patience and Fortitude, the grand lions that stand guard outside the New York Public Library gaze down the street, keeping an eye on people hurrying by, and those who stop to admire the beautiful and imposing building.

Library Way is paved with bronze plaques engraved with literary quotes. I’ve walked the street between 5th and Park avenues a number of times, just to read the inscriptions.

The other day, as I hurried home to our apartment, this plaque caught my eye:

I stopped, made sure I wasn’t blocking any one’s way (lest I attract the wrath of Fran Lebowitz who is living rent free in my mind after I watched ‘Pretend it’s a City’), and I snapped a quick photo with my phone.

‘Isn’t that true,’ I muttered under my breath as I picked up speed and walked at the only pace I’ve come to accept in this gorgeous city – ultra fast.

This blog has always been about stories. Mostly mine, sometimes mine intersected with others. My advocacy life is about sharing stories and encouraging others to understand the power and value of those stories. It’s stories we connect with because we connect with the people behind them.

My time in New York is wrapping up and I’ll be back in Melbourne soon. I’ll be home, starting a new job and I’m so excited. And part of the reason for that excitement is that I will still be working with people with diabetes and their stories.

In the world of advocacy – in my advocacy life – lived experience is everything. I can’t wait to hear more stories, meet more people and learn more. And keep centring lived experience stories. Because, after all, that’s what the universe – and the diabetes world – is truly made of. Just like the plaque says.

How was your Diabetes Awareness Month? I celebrated by taking a step back from most online activities and burying my head in the sand. Because, as always, Your Diabetes (Awareness Month) May Vary. #YDAMMV – get it trending!

I got COVID at the beginning of November and that was the definition of Not Fun. I was lucky in a lot of ways – I managed to take my first dose of anti-virals an hour after the ‘you’re positive’ lines came up on a RAT and was able to recover at home mostly. I easily accessed care when I needed it, and, in circumstances absolutely not normal for most, had heads of diabetes, and infectious diseases, departments at city tertiary hospitals calling to check in on me and make sure I had all I needed. (I know this is a perk of the work I do, and I recognise the remarkable privilege my work offers.)

I also spent November making some big life decisions and some big life moves (We’re in New York for the next three months) and that has all been kind of…big. I have never been so grateful of my incredibly supportive family and friends and, especially diabetes friends who have been an absolute bedrock on helping me through this time.

But here I am. It’s December. And it’s cold. December and cold are not words that generally go together for an Aussie sun-lover, but I am more than happy to be living in a city where Christmas carols suddenly make sense. Humming ‘Baby, it’s cold outside’ when the aircon is blasting, wearing a tank top, and sweating in 40°C heat is all sorts of oxymoron. This year, I’m wandering the streets in boots, a giant pompom adorning my beanie and wrapped in layers of coats and scarves, just as Mariah Carey intended.

Next week, I’m leaving New York and travelling to Lisbon for the IDF Congress. I’m so honoured to have been invited to give an Award Lecture, as well as speak in and chair a number of other sessions. The best part of this particular conference is the Living with Diabetes Stream which is dedicated to recognising diabetes lived experience. I can’t wait to hear from diabetes advocates from all over standing on stages and bravely, authentically and honestly sharing their stories. I wish more professional conferences had this sort of focus. And I also can’t wait to meet up with diabetes friends, some of whom I’ve not seen since before COVID. The Congress will be big and there will be a lot of it shared online. Keep an eye out!

Oh, and if you haven’t managed to get your #dedoc° voices scholarship application in yet, now is the time. The deadline has been extended by a few days and you have until next week to get yours in. You’d be mad not to, because become a #dedoc° voice means joining remarkable diabetes advocates from across the world and becoming part of a network like no other. Learning from dozens and dozens of people with diabetes who are there to do nothing but build community and support each other is incredible. Come join us! (Disclosure: I am Head of Advocacy for #dedoc°.)

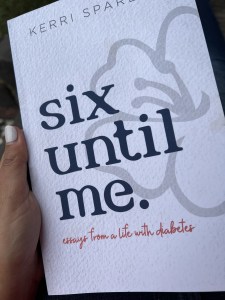

I’ve been rationing.

I only allow myself one story a day from Kerri’s new book, because I want to rediscover her writing little by little. I skipped over the contents page, so I would to be surprised when I worked out which stories from her Six Until Me blog made it into this new collection.

So it was with delight (and then tears) when I opened up to page 56, three stories into the section called ‘Diabetes in the Wild’ and saw my favourite ever diabetes in the wild story.

Kerri tells this tale beautifully, and exactly as it happened. I know, because I was there. The general gist is that on one her visits to Australia, Kerri and I were sitting outside in the Melbourne sunshine enjoying a coffee. At the next table was a woman and her daughter. When she heard us talking about diabetes, she looked up and joined our conversation, hungry to hear about our diabetes lives, and sharing with us that her daughter had been recently diagnosed. It was only a short chat, but as is often the case with diabetes in the wild stories, it has stayed with me, and I thought about the woman and her daughter each time I walked by that cafe.

Reading the story again in Kerri’s new book, I remembered that day – the perfect blue sky, the frothy tops of our coffees, the way that we were talking a million words a minute as we tend to do when we are together. And I also remembered how five years later I had another chance encounter with the woman from the cafe. ‘You were both so lovely & made me feel so much better,’ she said. ‘I was so glad for your openness and the hope it gave me! I always wanted to tell you that.’

Kerri’s stories are full of the humanity of diabetes. It’s one of the reasons her blog was so popular for the 14 years she wrote it, and why her occasional posts now are so welcome and gratefully received by people in our diabetes community. Her writing is real and generous, and rereading each post is testament to why storytelling is just so damn powerful when it comes to healthcare. I may live on the opposite side of the world to Kerri, exist in an upside down time zone and have to navigate a completely different healthcare system, but there is a familiarity to every single word she writes.

If you’ve never read Kerri’s writing before, this book is the a great place to start. And if you have, the book is a brilliant collection to have on your bookshelf, to pull down every now and then, open at any random page and envelope yourself in her magical storytelling.

And so, Kerri: Congratulations on this book, my darling friend. I remember you once wrote about the friends that live inside your computer. I’m delighted that now, I have you living inside this book and on my rainbow bookshelf. You’ll be alongside the blue spine-d books of Helen Garner, David Sedaris and Jhumper Lahiri – some of my favourite writers. Which is exactly where you belong.