Three days in Vienna is never going to be enough, and neither were three days at ATTD. But mother guilt is a very strong motivator for getting back home as quickly as possible.

This is the second ATTD conference I attended. Last year, I returned a little bewildered because it was such a different diabetes conference to what I was used to. But this year, knowing what to expect, I was ready and hit the ground running.

There will be more to come – this is the initial brain dump! But come back from more in coming weeks. Also, if you emailed me, shot me a text, Facebooked me, Tweeted me or sent me a owl last week, I’ll get back to you soon. I promise. Long days, and long nights made me a little inaccessible last week, but the 3am wake up thanks to jet lag is certainly helping me catch up!

So, some standouts for me:

DIY

The conversation shift in 12 months around DIY systems was significant. While last year it was mentioned occasionally, 2018 could have been called the ATTD of DIY APS! Which means that clearly, HCPs cannot afford to think about DIY systems as simply a fringe idea being considered by only a few.

And if anyone thinks the whole DIY thing is a passing phase and will soon go away, the announcement from Roche that they would support JDRF’s call for open protocols should set in stone that it’s not. DANA has already made this call. And smaller pump developers such as Ypsomed are making noises about doing the same. So surely, this begs to the question: Medtronic, as market leaders, where are you in this?

It was fantastic to see true patient-led innovation so firmly planted on the program over and over and over again at ATTD. After my talk at ADATS last year – and the way it was received – it’s clear that it’s time for Australian HCPs to step up and start to speak about this sensibly instead of with fear.

Nasal glucagon

Possibly one of the most brilliant things I attended was a talk about nasal glucagon, and if diabetes was a game, this would be a game changer! Alas, diabetes is not a game, but nasal glucagon is going to be huge. And long overdue.

Some things to consider here: Current glucagon ‘rescue therapy’ involves 8 steps before deliver. Not only that, but there are a lot of limitations to injectable glucagon.

Nasal glucagon takes about 30 seconds to deliver and is far easier to administer and most hypos resolved within 30 minutes of administration. There have been pivotal and real world studies and both show similar results and safety. Watch this space!

Time in Range

Another significant shift in focus is the move towards time in range as a measure of glucose management rather than just A1c. Alleluia that this is being acknowledged more and more as a useful tool, and the limitations of A1c recognised. Of course, increasing CGM availability is critical if more people are going to be able to tap into this data – this was certainly conceded as an issue.

I think that it’s really important to credit the diaTribe team for continuing to push the TIR agenda. Well done, folks!

BITS AND PIECES

MedAngel again reminded us how their simple sensor product really should become a part of everyone’s kit if they take insulin. This little slide shows the invisible problem within our invisible illness

Affordability was not left out of the discussion and thank goodness because as we were sitting there hearing about the absolute latest and greatest tech advantages, we must never forget that there are still people not able to afford the basics to keep them alive. This was a real challenge for me at ATTD last year, and as technologies become better and better that gap between those able to access emerging technology and those unable to afford insulin seems to widening. We cannot allow that to happen.

Hello T-Slim! The rumours are true – Tandem is heading outside the US with official announcements at ATTD that they will be supplying to Scandinavia and Italy in coming months. There are very, very, very loud rumours about an Australian launch soon but as my source on this is unofficial, best not to add to the conjecture.

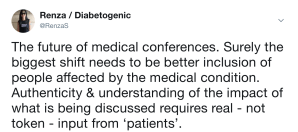

How’s this for a soundbite:

GOLD STARS GO TO….

Massive congrats to the ATTD team on their outstanding SoMe engagement throughout the conference. Not a single ‘No cameras’ sign to be seen, instead attendees were encouraged to share information in every space at the meeting.

Aaron Kowalski from JDRF gave an inspired and inspiring talk in the Access to Novel Technologies session where he focused on the significant role PWD have in increasing access to new treatments and his absolute focus on the person with diabetes had me fist pumping with glee!

Ascensia Diabetes packed away The Grumpy Pumper into their conference bag and sent him into the conference to write and share what he learnt. Great to see another group stepping into this space and providing the means for an advocate and writer to attend the meetings and report back. You can read Grumps’ stream of consciousness here.

Dr Pratik Choudhary from the UK was my favourite HCP at ATTD with this little gem of #LangaugeMatters. Nice work, Pratik!

ANY DISAPPOINTMENTS?

Well, yes. I am still disappointed that there were no PWD speaking as PWD on the program. This is a continued source of frustration for me, especially in sessions that claim to be about ‘patient empowerment’. Also, considering that there was so much talk about ‘patient-led innovation’, it may be useful to have some of those ‘patient leaders’ on the stage talking about their motivations for the whole #WeAreNotWaiting business and where we feel we’re being let down.

I will not stop saying #NothingAboutUsWithoutUs until I feel that we are well and truly part of the planning, coordination and delivery of conferences about the health condition that affects us far more personally that any HCP, industry rep or other organisation.

DISCLOSURE

Roche Diabetes Care (Global) covered my travel and accommodation costs to attend their #DiabetesMeetup Blogger event at #ATTD2018 (more to come on that). They also assisted with providing me press registration to attend all areas of ATTD2018. As always, my agreement to attend their blogger day does not include any commitment from me, or expectation from them, to write about them, the event or their products. It is, however, worth noting that they are doing a stellar job engaging with people with diabetes, and you bet I want to say thank you to them and acknowledge them for doing so in such a meaningful way.

‘It doesn’t, but it will get easier. Think of it like this… You’re in your car and you’ve just driven past a horrific car accident. You can’t stop, you have to keep driving, but you are driving very, very slowly because there is a lot of traffic backed up. You’re shocked and can’t believe what you have just seen. It’s gruesome. You look in the rear view mirror and you can still see it – all the details, all the goriness, all the pain.

‘It doesn’t, but it will get easier. Think of it like this… You’re in your car and you’ve just driven past a horrific car accident. You can’t stop, you have to keep driving, but you are driving very, very slowly because there is a lot of traffic backed up. You’re shocked and can’t believe what you have just seen. It’s gruesome. You look in the rear view mirror and you can still see it – all the details, all the goriness, all the pain.  A reminder of how the whole Spare a Rose thing works:

A reminder of how the whole Spare a Rose thing works: