You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Lived experience’ category.

Ten years ago, Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott appointed himself as the Minister for Women. Much has been written about the message this sent and what the government of the time really thought about women, despite the carefully framed rhetoric being spewed in press releases and at doorstop press conferences. But this post is not a lesson in Australian politics. It merely sets the scene for me to speak about the underhanded ways that those whose voice should be heard are silenced.

Diabetes advocacy sits in an environment that often resists the voices of those most affected by diabetes, at times in somewhat sneaky ways. A wolf in sheep’s clothing in advocacy comes in the form of anyone claiming to advocate by ‘being the voice’ of people with diabetes, which is problematic not least because we have our own voices and don’t need others to speak for us. Being adjacent to diabetes does not give anyone license to speak on our behalf. In fact, the very idea that anyone thinks that they can represent those who should be centred is offensive.

It matters, by the way. When our insights are not the ones being heard, we find ourselves in a cycle of misunderstanding and misrepresentation. Our perspective must be heard because it is inevitably comes with the reality of diabetes. When a person with diabetes is asked about why we need to invest in better diabetes care, have better access to drugs and technology or improve funding in diabetes research, we will speak of how improved care leads to better engagement with our healthcare professionals, reduced emotional load and the resulting increased time we can spend with loved ones and being productive at work. We will speak about how increased access can equal decreased burden for us and what that means in our real lives. And we will speak about how research is the gateway for us to have better understanding of our diabetes, helping us make more informed decisions, and speak to how research has changed our lives to date. We speak about hope authentically because we hold onto it with both hands.

Someone speaking ‘on our behalf’ will inevitably focus on reducing burden to the health system (which often makes us feel as if we’re to blame for overwhelmed and overrun hospitals and adds to diabetes stigma) or resort to listing diabetes-related complications, a familiar trope that sounds like a shopping list that does well to scaring us! I spent years being a spokesperson for diabetes organisations and always ensured that the reality of day-to-day diabetes was part of the discussion, not just the rehearsed talking points that tell nothing of the people behind the numbers. Even more importantly, I learnt very early on in my own advocacy when it was not my voice that should be heard and ensured I had a network I could reach into to find the right person. I estimate that about ninety percent of the time I’m asked to give comment, I point whoever is asking in the direction of someone far better positioned to share their lived experience.

This year brought with it a new role where it was essential that I step into the background. I now find myself in the incredibly fortunate position of working with unbelievably brilliant grassroots and community advocates doing truly life changing work with people with diabetes across India. I am not here to tell their stories or about their work. I wouldn’t do it justice – I have more than enough self-awareness to know that. I recognise that they are the protagonists of their narrative. They are the ones doing living the experiences, doing the ground-breaking work, and pushing for change. My responsibility is to be an ally and a supporter, doing what I can to amplify their voices rather than overshadow them. Perhaps this speaks to my own confidence in my abilities as an advocate that I don’t feel threatened by others who are raising their voices. Effective advocacy thrives on collaboration and shared leadership, and I admire those in the advocacy world who willingly take a step back. I think it’s fair to say that others also see those who do that; and also those who do not.

There are more insidious and damaging ways that our voices are silenced. Let’s go back for a moment to our former Prime Minister. I said earlier that he made himself Minister for Women. Except, he didn’t. In fact, he abolished the position and moved it into the Office of PM and Cabinet, removing the seniority and decision-making powers it had previously held. Sure, he appointed Michaela Cash as an advisor, but this was no more than an exercise in tokenism. The reality was that the PM would have final control over decisions affecting women. Abbott bristled when questioned about his decision, refusing to listen to the myriad women and women’s groups criticising the move, instead responding defensively.

I use this as an example when consulting organisations about effective engagement and how to address commentary from the community they work with and for. Receiving criticism can be uncomfortable. However, by being open to how community responds and the feedback they generously offer, it is an opportunity for improvement and collaboration, rather than a threat to be neutralised. It’s incredibly disappointing when organisations respond by attempting to discredit or question the motives and expertise of those with lived experience or suggest that negative comments are part of efforts underpinned with ulterior motives. It’s disheartening to hear implications that individuals offering critical perspectives are merely being influenced by others, disregarding their ability to form independent thoughts and opinions. This is simply another way that community voices are effectively silenced, and proves to the community that contributions from those who should be heard are not valued at all.

I speak a lot about allyship as a pivotal force in including and amplifying rather than excluding and silencing the voices of those with lived experiences. Allyship is an active commitment to placing people with diabetes at the forefront of conversations; featuring them in all levels of decision making; putting them in the rooms where things happen. True allyship involves listening to and acting upon the needs and concerns of people with diabetes, even when what is being said is difficult to hear. What it isn’t is fantastic window dressing. We see right through that.

I wrote this piece while listening to Black Oak Ensembles 2019 album, ‘Silenced Voices’. It’s stunning.

On November 14, the world will literally light up in blue to celebrate World Diabetes Day. And here in Melbourne, an event highlighting one of the most important issues in diabetes today will be held. The entire event will be dedicated to how the global diabetes community is coming together to work to #EndDiabetesStigma. And you can be there!

I’m delighted to be sharing the hosting seat with Dr Norman Swan, physician, journalist and host of Radio National’s Health Report. A veritable A-Team of people from the international diabetes community will be part of the event, sharing their experiences of diabetes stigma and why efforts to end it are so necessary and timely. There will be representatives from the global lived experience community, diabetes organisations and health professionals and researchers. You really don’t want to miss it!

For those able to attend in person, you’ll have a chance to catch up with diabetes mates. Any chance for opportunistic peer support is a great thing and I’m so pleased that I’ll be seeing diabetes friends that I’ve not seen for a very long time.

This isn’t only for Melbourne locals. There will be a livestream for people around the world to watch, share and be part of on social media. It’s free to attend and will be a great opportunity to see the diabetes world come together on a day dedicated to us!

Twenty-five years of diabetes. You bet that’s worth celebrating.

And I did, spending a couple of hours at a local Italian pasticceria with gorgeous family and friends, eating our way though pastries and drinking copious quantities of coffee. Is there a more perfect way for me to celebrate a quarter of a century – and over half my life – dealing with diabetes? I think not!

This commemorative coin was given to me by Jeff Hitchcock from Children with Diabetes. This is the organisation’s Journey Awards’.* What a fabulous recognition of the hard slog that is day-to-day life with diabetes. Of course, here in Australia there are Kellion medals, but these are not awarded until someone has lived with diabetes for 50 years. I love the idea of acknowledging years of diabetes along the way to that milestone, and am extraordinarily grateful to have this one on my dresser at home.

Because really, there is much to celebrate. Getting through the good, the bad, the ugly, the frustrating, the humorous, the wins, the losses, the CGM flat lines, the CGM rollercoasters, the times we nail a pizza bolus, the times we totally botch a rice bolus, the times we exercise and don’t have a crashing hypo, the hypos from out of nowhere, the stubborn highs that make no sense, the visits to HCPs that feel celebratory, the visits that make us feel like crap, the fears of the future and the present, the tech that works, the tech that makes things more difficult, the stigma, the desperation of wishing diabetes away, the horrible news reports, the crappy campaigns that position diabetes negatively and those of us living with it as hopeless, the great campaigns that get it right, the allies cheering us on. All of these things – all of them – form part of the whole that is me and my life with diabetes.

Happy diaversary to me! And thank you to the people along for the ride. How lucky I am to have their love and support in my life.

As for diabetes. I still despise it intensely. I still wish for a life without it. I still believe I deserve a cure. At the very least, I deserve days where diabetes is less and less present.

I am so forever and ever hopeful for that.

More diaversary musings

*More details of CWD’s Journey Awards can be found here. Please note that they are only shipped to US addresses due to postage costs.

‘What would the ideal campaign about diabetes complications look like?’

What a loaded question, I thought. I was in a room full of creative consultants who wanted to have a chat with me about a new campaign they had been commissioned to develop. I felt like I was being interrogated. I was on one side of a huge table in a cavernous boardroom and opposite me, sat half a dozen consultants with digital notepads, dozens of questions, and eager, smiley looks on their faces. And very little idea of what living with diabetes is truly about, or just how fraught discussions about diabetes complications can be.

I sighed. I already had an idea of what their campaign would look like. I knew because more than two decades working as a diabetes advocate means I’ve seen a lot of it before.

‘Well,’ I started circling back to their question. ‘Probably nothing like what you have on those storyboards over there’. I indicated to the easels that had been placed around the room, each holding a covered-over poster. The huge smiles hardened a little.

Honestly, I have no idea why I get invited to these consultations. I make things very hard for the people on the other side of the table (or Zoom screen, or panel, or wherever these discussions take place).

I suppose I get brought in because I am known for being pretty direct and have lots of experience. And I don’t care about being popular or pleasing people. There is rarely ambiguity in my comments, and I can get to the crux of issue very quickly. Plus, consulting means getting paid by the hour and I can sum things up in minutes rather than an afternoon of workshops, and that means they get me in and out of the door without needing to feed me. I think the industry term for it is getting more bang for their buck.

I suggested that we start with a different question. And that question is this: ‘How do you feel when it is time for a diabetes complication screening’.

One of the consultants asked why that was a better question. I explained that it was important to understand just how people feel when it comes to discussions about complications and from there, learn how people feel when it’s time to be screened for them.

‘The two go hand in hand. I mean, if you are going to highlight the scary details of diabetes complications, surely you understand that will translate into people not necessarily rushing to find out more details.’

I told them the story I’ve told hundreds of times before – the story of my diagnosis and the images I was shown to convey all the terrible things that my life had in store now. Twenty-five years later, dozens and dozens of screening checks behind me, and no significant complication diagnosis to date, and yet, the anxiety I feel when I know it’s time for me to get my kidneys screened, or my eyes checked sends me into a spiral of fret and worry that hasn’t diminished at all over time. In fact, if anything, it has increased because of the way that we are reminded that the longer we have diabetes, the more likely we are to get complications. There is no good news here!

‘But people aren’t getting checked. They know they should, and they don’t. And some don’t know they need to. Or even that there are complications,’ came the reply from the other side of the table.

Now it was me whose face hardened.

‘Let’s unpack that for a moment,’ I said. ‘You have just made a very judgemental statement about people with diabetes. I don’t do judgement in diabetes, but if you want to lay blame, where should it lie? If you’re telling me that people don’t know they need to get checked or that there are diabetes complications, whose fault is that?’

I waited.

‘Blaming people or finding fault does nothing. That’s not going to help us here. You’ve been tasked to develop something that informs people with diabetes about complications – scary, terrifying, horrible, often painful – complications. Do you really want to open that discussion by blaming people?’

Yes, I know that not everyone with diabetes knows all about complications, and there genuinely are people out there who do not fully understand why screening is important, or what screening looks like. The spectrum of diabetes lived experience means there are people with a lot of knowledge and people with very little. But regardless of where people sit on that spectrum, complications must be spoken about with sensitivity and care.

The covers came off the posters around the room, and I was right. I’d seen it all before. There were stats showing rates of complications. More stats of how much complications cost. More stats of how many people are not getting screened for complications. More stats showing how complications can be prevented if only people got screened.

‘Thanks, I hate it,’ I thought to myself silently.

I spent the next half an hour tearing to shreds everything on those storyboards. We talked about putting humanity into the campaign and remembering that people with diabetes are already dealing with a whole lot, and adding worry and mental burden is not the way to go. I reminded them that telling us again and again and again, over and over and over the awful things that will happen to us is counterproductive. It doesn’t motivate us. It doesn’t encourage us to connect with our healthcare team. And it certainly doesn’t enamour us to whoever it is behind the campaign.

I wrapped my feedback in a bow and sent a summary email to the consultants the following day, emphatically pointing out that I am only one person with diabetes and that my comments shouldn’t be taken as gospel. Rather they should speak with lots of people with diabetes to get a sense of how many people feel. I urged them again to resist using scare tactics, or meaningless statistics. I reminded them that all aspects of the campaign – even those that might not be directed at people with diabetes – will be seen by us and we will be impacted by it. I asked that they centre people with diabetes in their work about diabetes.

But mostly, I reminded that anything to do with complications has real implications for people with diabetes. What may be a jaunt in the circus of media and PR for creative agencies is our real life. And our real life is not a media stunt.

Disclosure

I operate a freelance health consultancy. I was paid for this work because my expertise, just as the expertise of everyone with lived experience, is worth its weight in gold and we should be compensated (i.e. paid!) for it.

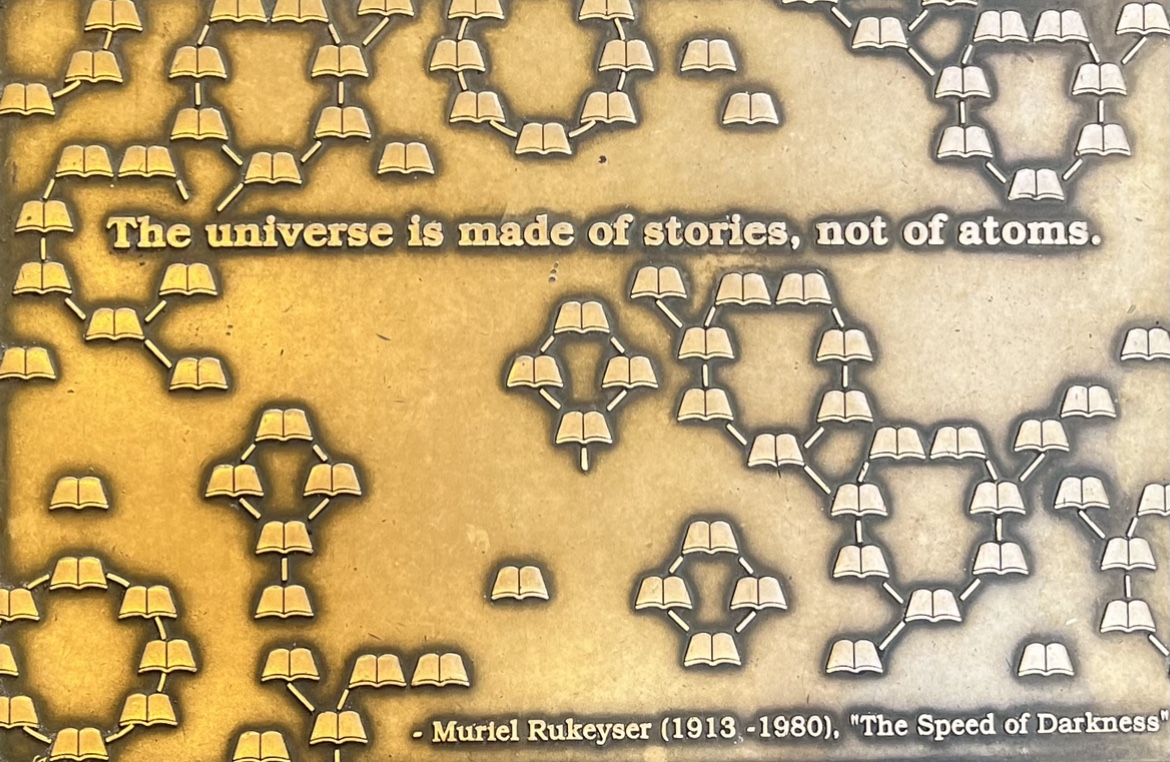

Manhattan’s East 41st Street is Library Way. Patience and Fortitude, the grand lions that stand guard outside the New York Public Library gaze down the street, keeping an eye on people hurrying by, and those who stop to admire the beautiful and imposing building.

Library Way is paved with bronze plaques engraved with literary quotes. I’ve walked the street between 5th and Park avenues a number of times, just to read the inscriptions.

The other day, as I hurried home to our apartment, this plaque caught my eye:

I stopped, made sure I wasn’t blocking any one’s way (lest I attract the wrath of Fran Lebowitz who is living rent free in my mind after I watched ‘Pretend it’s a City’), and I snapped a quick photo with my phone.

‘Isn’t that true,’ I muttered under my breath as I picked up speed and walked at the only pace I’ve come to accept in this gorgeous city – ultra fast.

This blog has always been about stories. Mostly mine, sometimes mine intersected with others. My advocacy life is about sharing stories and encouraging others to understand the power and value of those stories. It’s stories we connect with because we connect with the people behind them.

My time in New York is wrapping up and I’ll be back in Melbourne soon. I’ll be home, starting a new job and I’m so excited. And part of the reason for that excitement is that I will still be working with people with diabetes and their stories.

In the world of advocacy – in my advocacy life – lived experience is everything. I can’t wait to hear more stories, meet more people and learn more. And keep centring lived experience stories. Because, after all, that’s what the universe – and the diabetes world – is truly made of. Just like the plaque says.

Diabetes comes with a side serve of guilt in so many ways. Glucose levels above target? Guilty that I’m contributing to developing diabetes-related complications. Need to stop to treat a hypo? Guilty that I’m not participating fully in work, or focusing on family and friend. Forking out for diabetes paraphernalia? Guilty that the family budget is going to diabetes rather than fun stuff like (more) doughnuts from the local Italian pasticceria. Eating (more) doughnuts from the local Italian Pasticceria? Guilty that I’m not eating the way most diabetes dietitians recommend. Depositing the pile of diabetes debris on the bedside table? Guilty that I’m the reason the world is going to hell in a handbasket because of all the waste.

The other day, I did a show and tell of diabetes tech. I brought along all the things I use, and things I don’t use. I’d been asked to show and explain just how the tech I use works and what it all looks like, but I wanted to show that there were other options as well. The people I was speaking with had a general idea of what diabetes was all about but didn’t have the detail. So, while they understood what an insulin pump was, they didn’t really understand what it means when someone says, ‘I need to change my canula’.

I did a pump line change to show the process and all the components. I didn’t need to change my sensor, so I brought along a spare and a dummy kit that is used for demo purposes. I also had some disposable and reusable pens and pen tips, blood glucose strips and a meter, alcohol wipes and batteries for the devices that need them.

At the end of my demonstration and discussion, someone looked at all the debris. ‘That’s a lot of waste, isn’t it?’ I nodded. ‘It really is. And I think about that all the time. I hear people with diabetes lamenting just how much there is.’

‘It seems that what you use produces more waste than if you were using the reusable pens and a meter you showed us. Wouldn’t it be better for the environment if you did that?’

Yes, friend. Yes, it would. But it wouldn’t be good for me, my mental health or my diabetes. I was reminded of when our little girl was new and a man at the supermarket saw frazzled new-mum Renza covered in baby vomit and probably wearing my PJs, juggling baby and a box of Huggies and asked why I insisted on using disposable nappies rather than cloth. ‘Disposable nappies take 100 years to break down.’ In my new-mum fog, I looked at him, wondering what on earth I’d done to deserve this unsolicited approach, and said ‘Yes, I know. But if I had to deal with cloth nappies it would take me 100 seconds to break down.’ I blabbered on about other ways that we are more environmentally responsible, and then scurried away, adding environmental guilt to mother guilt and diabetes guilt.

Diabetes waste is horrendous. There’s a lot of it. And we should think about it. I love the work that Weronika Burkot and Type1EU led a few years ago. You can still find details of the Reduce Diabetes Technology Waste Campaign online. The project aimed to highlight the amount of diabetes tech waste one person with diabetes produces in 3 days, 1 week, 2 week and 1 month. It was startling to see the piles of trash accumulate.

But it can’t be solely the responsibility of the of us living with condition to address the issue. It’s brilliant that we talk about it – and we should do that. The Type1EU campaign got a lot of people thinking and talking about it for the first time. And we absolutely can and should do what we can to minimise our waste. I make sure that everything possible is recycled; I stretch out canula changes to four days when I feel it’s safe to do so; I restart sensors three or four times; I refill pump cartridges, sometimes to the point of them getting sticky; I use spent pump lines to tie the rose bushes in the garden; I’m using a fifteen year old pump – the last time I bought a new one was in 2013. I do all these things to try to reduce waste. I do what I can. I last changed my lancet one 2018. And, as an advocate, I have sat around tables with device manufacturers and begged that they consider how they can be more sustainable in their approach to diabetes tech, asking them what can be reused? What can be easily recycled? What can be removed from current packaging?

But the reality is, we don’t get a choice in how products are packaged. We don’t get to choose what the devices look like or the excess packages that surround them. We don’t get a say in the requirements of regulators who place stringent demands on manufacturers to make sure products meet safety obligations.

Laying into people with diabetes as needing to be more responsible without looking further upstream at just who is responsible for the product we pick up from the pharmacy, or have delivered to our door, seems unfair.

I gently pointed out to the person who was (most likely unintentionally) piling on the guilt with his comment about how I was contributing to the despair that is the condition of our environment, that his comment really was unjust and misplaced. To suggest that someone with a crappy medical condition that requires so much effort and attention, abandons the technology and treatments that go towards making it just a tiny bit less crappy is not really addressing the root problem. It can’t all be about individual responsibility. There needs to be scrutiny on everyone along the supply chain, but the least scrutiny and blame should lie at the feet of those of us with diabetes.

Sometime last year, I presented a webinar about how to be a good diabetes ally. The webinar was for a startup that would be working closely with people with diabetes. Earlier this week, someone who attended the webinar sent me this neat graphic which captured the main points of my presentation. I know that there are lots of other things that could be added, (and during my talk I covered more than what made this list), but I think that this is, perhaps, a good starting point. I’m especially pleased my point about avoiding hypo simulators made the cut!!

When I think of the diabetes allies I’ve worked with over the last 21 years in the diabetes world, I realise that their main strength is that they made point number one the foundation of their work. I find myself being drawn to the activities of those who centre people with diabetes in meaningful, not token, ways. They are the people who happily step into the shadows so that people with diabetes can be in the spotlight.

A real diabetes ally works with us. They stand with us, not speak for us, because when anyone claims to ‘be the voice of diabetes’ they are simply silencing people with diabetes. We have voices, we have words – our own words – we don’t need others to speak for us. Hand us the microphone.

Being an ally is easy. It really is.

More? I’ve written before about how healthcare professionals can be allies to people with diabetes when they see and hear stigmatising comments from their colleagues. A lot of what was in that post is relevant here too.