You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Diabetes’ category.

ISPAD has led the way when it comes to including people with lived experience of diabetes at their annual meeting. It was the first conference to work with #dedoc° to have a voices scholarship program. The society has included people with diabetes on the organising committee for some time. ISPAD has awarded the ‘Hero Award’ which recognises the work done by people in the community. And the conference scientific program involves people with diabetes speaking and chairing sessions.

And so, it was interesting to hear someone ask at last week’s meeting in Montreal whether there should be a limit to the involvement and number of people with diabetes.

I wasn’t actually in that session, but I certainly heard about it from many others. People seem to expect me to have words to say about these sorts of questions. Turns out I do – and so do other people. And there was quite a bit of discussion – both at the conference, and in an online group after I shared the question with members.

While the question may have been well intended, (I certainly don’t believe there was any malice in asking), it did make me bristle. The idea of limiting access to a diabetes conference to people with diabetes has never sat well with me. It reeks of gatekeeping. And it also sends the message that people with diabetes are ‘allowed’ at the discretion of others rather than having a right to attend.

I think that quantifying the number of any sort of participant is problematic, but I have always liked this pie chart drawn and tweeted by James Turner (@jamesturnereux, although he appears to no longer be on the cesspit site) from a Medicine X conference in 2017. I am pretty sure that I have already shared this somewhere in the #diabetogenic archives, because I think it’s great! What I like about this is that it recognises that everyone has an equal place to be there. That equilibrium does sit well with me!

I also like the comment from my friend, and researcher and fabulous diabetes advocate, Ashley Ng. We caught up today to discuss this issue, and she said ‘I don’t agree with a maximum, but I do think we need minimum representation by people with lived experience’.

But this isn’t just a matter of representation, and it’s not simple either. There is the broader issue of people with diabetes wearing more than one hat. Some may also be researchers, clinicians, involved in technology development, industry representatives and more. This certainly does point to the complexity of the ecosystem. When looking at the number of people with lived experience of diabetes, we draw the cohort from many different spaces.

But this in itself adds to the intricacies of the situation. In fact, it is something that I have spoken and written about for decades (most recently here) and my position is very clear, albeit not especially popular with everyone. I believe that people with lived experience who wear no other hat in the healthcare space must be prioritised for positions centring lived experience at conferences, in panels, on advisory groups and anywhere people with diabetes are intended to be represented. Why? Because these are usually the ONLY way for us to get a seat at the table. Those wearing other hats may find themselves able to access other pathways via their employment or professional settings.

This is why #dedoc° generally doesn’t offer scholarships to healthcare professionals and researchers. The voices program is for people with diabetes who otherwise would not be able to find a way to attend conferences and who don’t have other prospective funding opportunities. I am aware that HCPs and researchers have limited opportunities available to them, but there are funding streams and grants, and institutional supports that are simply not open to people with lived experience who do not have any professional affiliation. Of course, (and it shouldn’t need to be said, but I’ll say it anyway), I’m not minimising the experiences of those who bring both professional and personal perspectives. But there are so very few opportunities for people with diabetes who represent as community members only to find a seat at the table. Those seats should not only be reserved for us, but we should all work to protect them.

It would be remiss of me to not point out that there are indeed unique challenges for people who straddle the professional and lived-experience divide. This article (I am a co-author) was written by people with lived experience of diabetes and wearers of other hats and addresses some of the issues faced by people in this situation.

These discussions are always interesting, but they can be uncomfortable. And also frustrating. I would hope that we are far along the lived experience inclusion road to not have to justify the rights of people with diabetes to be part of conferences and other efforts. And rather than even suggesting gatekeeping, we should be looking at more ways to make access to these spaces easier, and focused on diversity of voices. Chelcie Rice says we should bring our own chair if there isn’t one already for us. I say, bring two or three and the people to fill them too. But honestly, we should be beyond that now, right? We should simply be able to walk into any space and take a seat.

Disclosure

ISPAD invited me to speak at this year’s meeting and covered by accommodation costs. Travel was part of my role at Breakthrough T1D.

Do you remember life before diabetes? It’s getting harder and harder for me to. I had 24 years without diabetes, and occasionally, I’ll look at a photo from the BD years and think about how much simpler my days were.

Today, I’m wondering how much I remember diabetes before I started using automated insulin delivery (AID). It’s been eight years. Eight years of Loop. Happy loopiversary to me! Diabetes BL (before Loop) felt heavier. And scarier. I remember those months just after I started looping and how different things felt. I remember the better sleep and the increased energy. I remember a lightness that I hadn’t experienced since I was diagnosed.

That’s now my “diabetes normal”. Life with Loop is simply easier than life BL. On the very rare occasions I’ve had to DIY diabetes, it’s been a jolt as I’ve realised just how truly bad I am at diabetes. Embarrassingly bad.

While there was a stark difference back then between people who were using DIYAPS and those who were using interoperable devices on the market, today that difference is less. AID systems are not just for people who choose to build one for themselves. These days, it’s so great to know that there are commercial systems available which means more people have access to AID. We can debate which algorithm is better or whether a commercial or an open-source system is better, but I think that’s a little pointless. If people are doing less diabetes and feeling happier, better and less burdened, it doesn’t matter what they’re using. Your diabetes; your rules!

Eight years on, and despite there being commercial systems I could access, I’ve decided to keep using Loop – the same system I started on 8 years ago. The changes I’ve made are the devices with which I am using Loop. My pink Medtronic pump has been retired, along with the Orange Link (which was obviously in a pink case). Instead, I now use Omnipod, a single device instead of two which has further simplified my diabetes. It’s also meant not worrying about a working back up Medtronic pump, and it means carrying less bulky supplies when travelling.

These may all seem like little things, but they add up.

My decision to not move to a commercial system has been based on a couple of different reasons. I always said that I wouldn’t move to something that required a trade-off whereby any of the convenience of Loop was compromised. I’ve been blousing from my iPhone or Apple watch since 2017, and I refused to let that go. In my mind, having to wrangle my pump from my bra or carry an additional PDM to bolus was a step backwards. Of course, this is now available on some commercial systems, and it’s been super cool to see diabetes friends have access to something that does make diabetes a little less intrusive.

The customisability of Loop has meant that my target levels are set by me and me alone. The lower limit on commercial systems is not what I like mine set at. I wasn’t prepared to sacrifice the flexibility of personalised settings fora one-size-fits-all approach.

I do understand that there are pros to having a commercial system. Having helplines to trouble shoot and customer support on call is certainly a positive. Knowing that an annual Loop rebuild (always anxiety inducing because …well, technology?) is upcoming is stressful. And the worry that the update will break something that’s been working perfectly.

And yet, measure for measure, the decision to continue to use Loop has been very easy.

I still thank the magicians behind open-source technologies for their brilliance and generosity every single day. I’m grateful for the algorithm developers, the people who have written step by step instructions that even I can follow, and I am so thankful for the people who have tried to make devices more affordable. I believe that device makers do genuinely want to make diabetes simpler and help ease the load of diabetes. But in my mind, it’s undeniable that user-led developments have been more successful in actually making diabetes easier. These magicians know firsthand just what it means to claw back from diabetes.

In the end, the goal for me has always been clear: I want diabetes to intrude in my life as little as possible, and I will avail myself of anything that helps. It’s why I continue to use an Anubis even though there is no out of pocket cost for G6 transmitters. Using an Anubis means I change my sensor when it’s getting spotty, not when the factory setting insists, and the transmitter last six instead of three months. See? Fewer diabetes tasks. Less diabetes. That’s the whole point. (And it’s also why I’m hesitant about moving to G7)

When I try to quantify how much less diabetes, I just come back to Justin Walker and his presentation at Diabetes Mine’s DData back in 2018 when he said ‘By wearing Open APS, I save myself about an hour a day not doing diabetes’. Eight years down the track, that’s 2,922 hours I’ve gained back. That’s almost 122 days. It may be thirty seconds here, a minute there. But it adds up. And that time is better in my pocket than in diabetes’.

And so, here I am. Eight years on. With diabetes in the background as much as it can be with the tools I have available to me. I still really don’t like diabetes. I still really resent it takes up the time and brain space it does, and I still want a cure for all of us. Damn, we deserve that.

But in the meantime, I’m going to keep leaning into what the community has done for the community and know how lucky I am to benefit from that knowledge and expertise. Never bet against the T1D community. We know exactly what diabetes takes from us every day. And exactly what it takes to give some of it back.

More on my experiences with Loop

That time I scared the hell out of healthcare professionals

What looping on holidays looks like

A list of how Looped changed my diabetes life (and all of it is still relevant today!)

Postscript

As ever, I’m very aware of my privilege. Access to AID is nowhere near where it should be. If we look at the Australian context, insulin pumps remain out of range for so many people with T1D thanks to outdated funding models. Remember the consensus statement developed last year? And beyond our borders, technology access varies significantly. As a diabetes community, we are not all beneficiaries from this tech until every single person with diabetes has access. And that starts with affordable, uninterrupted access to insulin, right through to the most sophisticated AID systems, to preventative treatments, to cell therapies.

This is a transcript of a talk I gave earlier this year to a European-based health consultancy and creative agency about my take on global diabetes community-based advocacy – the opportunities and challenges. The title I was given was ‘Making Engagement the norm rather than the exception’. AI did a remarkably decent job with this transcript, but I expect that there might be some clunky language in there that I missed when I read through it on a plane after being in transit for 27 hours straight. Or, I could simply have used clunky language. Either way, it’s my fault.

I often say that community is everything, but I want to begin by saying that it’s important to understand that there is no single, homogenous diabetes community. Everyone’s diabetes experiences are different. I truly believe that there are some issues that unite us all, but really, we are a very disparate group – something I have come to understand more and more the longer I have been involved in diabetes community advocacy. This poses possibly the largest challenge for everyone in this room wanting to work with “THE diabetes community” because if you’re looking for a group that agrees on everything and believes the same thing, I’m sorry to say that you’re going to be in for quite a ride!

But it is also the biggest opportunity – and the way to get an edge – because it gives anyone who works in the diabetes space – from healthcare professionals, researchers, industry, diabetes organisations, policy makers, the media – to roll up their sleeves and make a concerted effort to talk with a wide range of people with diabetes to understand our experiences and what we need. Look, I know that it would be easier for all of you if I said, ‘Speak with one person and then you’re good to go’, but that would be a lie. Sadly, a lot of people and organisations still believe this to be the case, and I have a great example to show you why that doesn’t work.

And that example? It’s me, hi, I’m the problem, it’s me.

A number of years ago, a researcher reached out to me with an invitation to be the ‘consumer representative’ on their project. After bristling at the term “consumer”, I asked what the project was about, and this is what they said, word for word because I wrote it down and have told this story a million times as a cautionary tale: ‘It’s a project on erectile dysfunction in men with type 2 diabetes, diagnosed over the age of 65.’

There was not a note of irony in this invitation. When I pointed out that I fit literally none of the categories in the study and then went on to point out that I am a woman; I have T1D; no erectile dysfunction; diagnosed at 24; was not within a decade of 65 years of age, the response was ‘Oh, but you have diabetes, so you’ll be great’.

Friends, I would not have been great.

For the purposes of this discussion, when I say diabetes community, I am referring to people with lived experience of diabetes. There is a lot of cross over in the diabetes advocacy space, and there are many examples I can point to that show how valuable advocacy efforts can be when people with diabetes are involved in efforts led by diabetes organisations or other stakeholders. In fact, at the end of last year, we saw a brilliant example of that with Breakthrough T1D in Australia receiving $50.1 million in funding from the Australian government for their Clinical Research Network. This is the power of an organisation meaningfully engaging with their community to tell the story of why their advocacy is important. I mean, what is more compelling than hearing from people with diabetes and their families about how research holds the key to a better diabetes future?

I’d encourage you to look at Breakthrough T1D Australia’s socials to see just how beautifully they centred people with lived experience to get their message across, and how it was people with diabetes who literally marched on parliament to tell the story. The coordination of the campaign may have come from a passionate advocacy and comms team in an organisation, but the words were all people with diabetes. (For transparency: I work for Breakthrough T1D, formerly JDRF, but not for the Australian affiliate. I am, however, extraordinarily proud of what Breakthrough T1D Australia has achieved and so, so impressed with the way their communications campaigns are never about the organisation or staff, but rather about the community.)

I believe that our community excels in telling the stories of our lives with diabetes, what we need to make our lives better, what works in our communities and how we can better work together. Some standout examples of this include the #dedoc° community, and, in particular, the #dedoc° voices scholarship program. This is the only truly global community where diabetes advocates are not only present but are leading conversations. #dedoc° has no agenda other than to provide a platform for people with diabetes which results in diverse stories and experiences being heard. And it also means that organisations want to work with #dedoc° because it’s an easy way to connect with community. (And another point of transparency: I’m the Head of Advocacy for #dedoc°.)

Organisations that thrive on working with community demonstrate their commitment to improving the lives of people with diabetes in ways that matter. If you don’t know about the Sonia Nabeta Foundation (SNF), you really should! The foundation has a network of ‘warrior coordinators’ who provide peer support and a whole lot more! I have now had the honour of chairing sessions at international conferences with four of these warrior coordinators and I can say without a doubt that Hamida, Moses, Nathan and Ramadhan’s stories resonated and stayed with the audience way beyond the allotted ten minutes of their talks. Addressing the challenge of a limited workforce and resources by engaging and employing people with diabetes to educate and support younger people with diabetes is so sensible and clever. And the results are remarkable.

I have seen similar examples in India. Visiting Dr Archana Sarda’s Udaan centre in Aurangabad and Dr Krishnan Swaminathan’s centre in Coimbatore completely changed my understanding of peer-led education. And groups like the Diabesties Foundation and Blue Circle Diabetes Foundation (also in India) are prime examples of the successes we can expect when people with diabetes take charge of programs and lead diabetes education.

Seeing these examples firsthand lit a fire under me to challenge what we have been told in high-resourced countries like Australia, and here across high-income countries in Europe. Why is it that we, as people with diabetes, are told to stay in our lane and not provide education? We may be considered ‘higher resourced’, but people fall through cracks because they are not getting what they need. Health systems remain challenged and overwhelmed.

The challenge we have in places like Australia is that PWD are very clearly told that we are not qualified to provide education. Rubbish! Our lived experience expertise puts us in the prime position to do more than just tell our own story, and I believe we need to boldly push back on beliefs that only health professionals are equipped to fill education and knowledge gaps. Because in addition to what we know, the expertise we hold and our ability to speak in the language that PWD understand, we also know about ‘going to the people’ and not expecting a one size fits all approach to work.

It would be naïve to think that community-led, and -driven programs and initiatives aren’t already happening. Community is integral in providing information that PWD are desperate for, even with caveats about consulting HCPs. There are 24/7 support lines available in the community, something that is simply not available in most healthcare settings. And anyway, who better than others with diabetes to give practical advice on real life with diabetes than those walking similar paths? In the moment and with direct experience.

The #WeAreNotWaiting community was established to not just offer advice but develop technologies to improve lives of people with diabetes and continues to do so today. A five minute lurk in any of the online community groups dedicated to open-source technologies is all it takes to see people with diabetes who had been at the end of their tether with conventional care now thriving thanks to community intervention.

And that is replicated in low carb groups where community provides advice and education on how to eat in a way that is often not recommended by HCPs. People share experiences how they are flourishing thanks to making informed decisions to eat this way, and air their frustrations about how they are often derided by HCPs about those decisions. The support that comes from these groups is often just as focussed on how to deal with the healthcare environment when going against the grain (unintended pun) as sharing ideas and advice on how the science behind how low carb diets work.

T1D groups talk about incorporating adjunct therapies into their diabetes management, moving from a glucose-centric approaches to looking at other meds and interventions that can support better outcomes. GLP1s may not be approved for use by people with T1D, but they are increasingly being used off label because of their CVD and kidney protective nature. These community discussions include suggestions on how to have conversations with HCPs to ask about how adjunct therapies might help, including pushing back if there is a blanket ‘no, it’s off label’ response. Before anyone thinks this isn’t a good thing, I remind you that we still need prescriptions from our HCP before we can start on any new drug. We should be listened to when we ask to have a discussion about new and different ways to manage our diabetes.

And there are also businesses led by community that have stepped into spaces that are traditionally organisation or HCP-led. A few years ago, Aussie woman Ashley Hanger started Stripped Supply to fill a massive gap when diabetes supplies could no longer be ordered online and shipped, instead necessitating a backstep where PWD had to go into pharmacies to pick up supplies. Ashley’s start up gave the people what we wanted and meant that, for a small subscription fee, supplies could be straight to our doors again. And it’s run by community – what’s better than that?

There is contention about people with diabetes working with industry, and that is a conversation for another time. But I will say that when we have people with diabetes involved in the development of the devices that we use and/or wear on our bodies every day, the end products are better. That’s just a fact. When you have people with diabetes employed by device manufacturers writing education and instruction manuals for those devices, they make sense because they are written from the perspective of someone who actually understands the practical application of using those devices. It’s a massive opportunity for industry to engage – and employ – people with diabetes. Way to get an edge!

What I would say to everyone here today is that if you are not directly working with people with lived experience of diabetes, you are missing out on the biggest piece of the diabetes stakeholder puzzle. But you have to do it meaningfully and perhaps the biggest challenge I face is dealing with the rampant tokenism that exists in the diabetes ecosystem. For my entire advocacy career I have been urging the implementation of meaningful engagement, and to be honest, a lot of the time I feel that I have failed in those attempts. Every time I see a crappy program or campaign come out of somewhere that claims to work with community, I realise that people with diabetes are being used in possibly the most nefarious way possible: to ‘lived experience wash’ the work of the organisation. I wrote a piece earlier this year about this and was completely and utterly unsurprised to receive comments justifying poor attempts of consultation.

But then, I see something like the video I am going to finish with from Breakthrough T1D in the UK, and I know that there is intent there to do the right thing and do it properly. To involve people with diabetes from the beginning, and centre them throughout the work. The result is a beautiful piece of storytelling that has been shared across the globe. I don’t know the metrics, and quite frankly, I don’t care. All I need to see is the response from the community to know and understand that this hits the spot. And you can too with your work if you engage properly. We’re here to help.

You can watch What a Cure Feels Like, the Breakthrough T1D UK video that concluded my talk here.

Disclosure

I was invited by a health consultancy firm to give a talk to fifty people working on public-facing health campaigns (NDA, can’t say anything more) and then run a workshop about working with lived experience representatives. I was paid for my time to present and prepare for the session, and reimbursed for ground transfers to and from the location of the meeting.

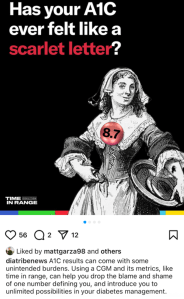

Earlier this week, diaTribe shared this on their Instagram:

It did not sit well with me at all. And I don’t understand the reference to stigma.

A1C is flawed. People with diabetes have been saying this for decades. To have our overall diabetes management measured by an average that gives no nuance to other factors is not a good way to assess health or guide treatment.

CGM changed all that, with visibility into just what is going on with glucose levels at all times. I finally understood why I was so tired some mornings, despite eight solid hours of sleep with in-range numbers at bedtime and at waking. I saw the rollercoaster nights, or the hours at time I was low. It became very clear that my nighttime glucose adventures were exhausting me.

As more people had access to CGM, TIR was heralded as the new gold measuring standard. And it was everywhere. I wrote and spoke about it a lot because the real-time data gave me a clearer understanding of my diabetes. But with that excitement came a gnawing discomfort: were we just swapping out one metric for another?

After a couple of years of TIR, and with the advent of newer, smarter AID systems there was a new kid on the block: Time in Tight Range (TITR). Target upper and lower limits were tightened and there were expectations of remaining within those ranges.

I nodded along because I was, for the most part, comfortably sitting within those number thanks to Loop. And yet, my discomfort grew. More pressure, more expectations on people with diabetes based solely on numbers, and a continued widening of the gap between people with access to tech and those without.

At ATTD a couple of months ago, there was the announcement of a new metric: Time in Normo-Glycaemia – TING! (There is no exclamation mark after the acronym, but it reminds me of the celebratory sound my kitchen timer makes when a cake is done baking, and that deserves festive punctuation.) And horrifyingly, to this #LanguageMatters boffin, the new acronym includes the word ‘normo’. Language position statements have always, always advised against using the word normal/normo. The word shapes attitudes that contribute to stigma. In one study, 85% of PWD surveyed found the word unacceptable.

These measures still focus on one thing: our glucose numbers. There are goals for the percentage of time each day we should be aiming to be in (ever-tightening) range. So, effectively, the HbA1c percentage has been replaced with time in range percentage. It’s still focusing on nothing more than numbers. It still sets us up for a pass/fail framework.

A1C, in itself, is not stigmatising. It’s a number. The language used when discussing A1C can be stigmatising. Attributing success in diabetes to an A1C number can be stigmatising. Being told we’re failing for not reaching an A1C of a certain number is stigmatising. But all of those things are true of TIR.

Before anyone comes at me and tells me that PWD should be able to have numbers within a tight range, of course that’s true. But isn’t that already the goal of our diabetes management? Isn’t that the point with all the glucose measuring, insulin dosing, and considering the bazillion other things we do to manage diabetes? I don’t know anyone with diabetes who does the work with a goal of glucose number of 17.0mmol/l; an HbA1c of 14%; a TIR/TITR/TING of 11%.

But replacing one measure for another still traps us in a numbers-only mindset. How is ‘What’s your TIR?’ really any different to ‘What’s your A1C?’ Does it free us from being metrics-focused? (Some might argue that it ties us to numbers even more with daily updates about how we’re tracking.) Does it address stigma?

I’m not sure it does. I’m not convinced that there is any relevance at all to stigma in this conversation. And I’m a little annoyed at the conflation. Diabetes-related stigma is very topical now, thanks to important efforts by PWD, community groups, researchers and clinicians in the diabetes space. If I was being cynical, I’d suggest that this is an opportunistic attempt to jump on the buzz movement of the moment without meaningfully engaging with what stigma really is or how any type of metric can contribute to it, depending on how it’s framed and used.

Postscript – but possibly the most important part…

And finally, but perhaps most importantly: the very idea that we are suggesting this is the gold standard when it is inaccessible to the vast majority of people with diabetes is just so out of touch. According to the diaTribe article that accompanied the Instagram post I shared earlier, worldwide 9 million people are currently using CGM as part of their diabetes management. The IDF’s latest Atlas data, (launched last month) reports that there are about 589 million adults (20-79 years) with diabetes across the world. That doesn’t include children and young people. (1.8 million young people are estimated to be living with T1D.)

Isn’t this one way stigma takes a hold? When we’re talking about targets that are only available to the small fraction of the diabetes community who can access the tools to achieve them. Setting standards around tech that most can’t obtain doesn’t just ignore reality—it reinforces the stigma of not measuring up.

It’s not an exaggeration when I say that I give thanks to Frederick Banting every single day. I have a photo of him in my office next to an artwork of the word HOPE. And anytime I am sitting at my desk working or sitting in my office reading and find myself looking at the photo, I say these words: ‘Thank you for my life’.

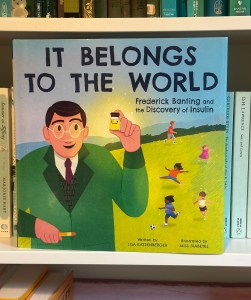

The story of the discovery of insulin has been told many times. There are some excellently researched and detailed accounts of what it took to get to the ‘Eureka!’ moment, as well as documentaries and a couple of feature length movies. But despite having a dozen or so books on my shelf that tell the story, I was so excited to order this version:

‘It Belongs to the World’ is a gorgeous children’s book by Lisa Katzenberger, and illustrated by the supremely talented Janina Gaudin, (better known online as Miss Diabetes), is a truly beautiful retelling of the story.

While it would make sense to say that this book would make a great gift for a child with diabetes, or parent living with diabetes to read to their kids, really, it’s is a book for everyone. Stories like this should be told over and over, and not just to those of us for whom it is personally relevant. Everyone should learn about the brilliance of scientific discovery. It’s a reminder of the importance of research, and how research saves lives each and every day. It serves to encourage us to get behind research efforts, as a participant or donor if possible. And it gives hope for what still lies ahead.

Oh, and it’s always good to support creators in our community. What a brilliant awareness raising effort from Janina and Lisa. Go get your copy now!

Disclosures

None! I paid for my own copy of this book through my local bookstore. They had to get it in, so you may need to order it. (Or it’s available to order through Amazon.)

One of the things of which I am most proud is seeing how the language matters movement has really made people stop and think about how we communicate about diabetes. Of course, there’s still a long way to go, but it is very clear that there have been great strides made to improve the framing of diabetes.

One area where there has been a noticeable difference is at diabetes conferences. I’m not for a moment suggesting that there is never negative language used at conferences and meetings, but the clangers stand out now and are likely to be highlighted by someone (i.e. #dedoc° voices) in the audience.

Earlier this month, the 75th IDF World Congress was held in Bangkok. Sadly, there was no livestream of the Congress, but it’s a funny thing when you have a lot of friends and colleagues (i.e. #dedoc° voices) in attendance. It meant that I had my own livestream. Sadly, the majority of what I was being sent were the language clangers.

But let’s step back a week or so to before the Congress even started. I was feeling horrendous and my brain was in a foggy, virus haze, yet I still managed to be indignant and vent at the horrendously titled ‘World Adherence Day’ which was being ‘celebrated’ on 27 March. Here is my post from LinkedIn, which has been viewed close to 12,000 times:

What I didn’t say in my post was that the IDF had eagerly endorsed the day with a media release and social media posts. My LinkedIn post took all my energy for that day, and I didn’t get a chance to follow up with the IDF. Plus, I assumed their attention would have been focused very much on the upcoming Congress.

Also, I hoped that it was a one-off misstep. I mean, surely the organisation had learnt its lesson after the Congress in South Korea when I boldly challenged incoming-president Andrew Boulton for his suggestion that people with diabetes need some ‘fear arousal’ to understand how serious diabetes is. You can see the video of my response to that at the end of this post and read the article I co-authored (Boulton was another co-author) about language here.

Alas, I was wrong. Just days before the Congress started, I saw flyers for this session shared online:

I was horrified and commented on a couple of the posts I saw. I was surprised to see some responses from advocates which amounted to ‘We can deal with it when we get there.’ Here are reasons that isn’t good enough. Firstly – not everyone is there, so all they see is the promotional of an event, comfortably using stigmatising language. It suggests that this language and the meaning behind it is okay. The discussion shouldn’t be happening after the fact. In fact, the question we should be asking is: HOW did this even happen? Where were the people with lived experience on the organising committee of the Congress speaking up about this? Did they get to see it before it was publicised? And how did the IDF miss it? This is, after all, the organisation that launched a ‘Language Philosophy’ document in 2014 (which sadly seems to be unavailable online today). It’s also the organisation that has invited me to give a number of talks about the importance of using appropriate and effective communication to IDF staff, attendees of the Young Leaders Program and as an invited speaker at a number of Congresses.

A major sponsor at the IDF Congress seemed to be very excited about the word adherence. In fact, it appeared over and over in their materials at the Congress. Here is just a couple of their questionable messaging sent to me by people (i.e. #dedoc° voices) attending the Congress:

I will point out that the IDF obviously understands the impact of stigma on people with diabetes and the harm it causes. There were sessions at the Congress dedicated to diabetes-related stigma and how to address it. In fact, I had been invited to give one of those talks. But what is disappointing is that despite this, terminology that contributes to stigma is being used without question.

I wasn’t at the Congress but from what I saw there was indeed a vibrant lived experience cohort there. #dedoc° had a scholarship program, and, as usual, there was a Living with Diabetes stream. However, I will point out that the LWD stream was not chaired by a grassroots advocate as has been the case for all previous LWD streams. It was chaired by a doctor with diabetes and while I am in no way trying to delegitimise his lived experience, I am unapologetically saying that this is a backwards step by the IDF. When there is an opportunity for a person with diabetes who is not also a health professional is given to a health professional or a researcher, that’s a missed opportunity for a person with diabetes. There were seven streams at the IDF Congress. All except for one are 100% chaired by clinicians and researchers. Only the LWD stream is open to PWD. I know that when I chaired the stream, the four members of the committee were diligent about looking through the entire and identifying any sessions that could be considered problematic for people with diabetes. It appears that didn’t happen this time.

All of this points to a persistent disconnect. It is undeniable that the language matters movement is growing, but it is still not embedded across the board—even within organisations that should know better. If we are serious about addressing stigma and centring lived experience in diabetes care, then language can’t be an afterthought or a debate to have after the posters are printed and the sessions are underway. It must be part of the planning and the review process. The easiest way to connect the dots is to ensure the lived experience community is not only present, but also listened to, respected, and in positions to influence and lead. We are long past the point where being in the room or offered a solitary seat is enough – the room is ours; we are the table.

Postscript:

I have written extensively on why language – and in particular the word ‘adherence’ – is problematic. It’s old news to me and to many others as well. This piece isn’t about that. But if you want to know why it’s problematic, here’s an old post you can read.

Disclosures:

I was an invited to give a talk about diabetes-related stigma at the IDF Congress in Bangkok, but disappointingly, had to cancel my attendance due to illness. The invitation included flights and accommodation as well as Congress registration. I was also on the program for two other sessions and was due to present to the YLD Program.

Other IDF disclosures: I have been faculty for the YLD Program for the last 10 years; I chaired the LWD Stream at the 2019 Congress and was deputy chair of the 2017 Congress.

I’ve been unwell.

And so, I’ve had time to think. Mind you, I’ve found it difficult to form thoughts properly, thanks to the brain fog that is impacting my attention span and ability to think things through to a conclus…oh look! The leaves on the trees in the garden are changing. I should buy the last plums when I go to the fruit and veg shop, and bake a plum cake. That would be delici… Are mandarins in season yet? Ooh, a puppy!

Anyway, back to trying to focus on what I’ve been randomly and messily thinking about.

On my last day at ATTD in Amsterdam, I wound up with a very weird pain flare that meant I could barely move. I put two and two together, came up with the wrong answer and decided it was thanks to arthritis and spent the day before my flight desperately trying to sleep it off so I would be okay to navigate Schiphol Airport and get myself home. I did make it home, but not without wheelchair assistance at each airport, and in excruciating pain for the entire long trip home.

Turns out, it wasn’t arthritis. It also wasn’t diabetes, but that didn’t stop me from trying to connect non-existent dots.

The day before the paralysing pain flare, I woke at 3am with my Dex alarm wailing. I was low. Very low. For five hours. You know, one of those lows that just won’t quit. One of those lows that simply won’t respond to massive quantities of glucose. I ended up throwing up after force feeding myself jellybeans and guzzling juice from the minibar, which was all just lovely. (And yes – I realised I had some inhalable glucagon with me AFTER the fact … but in my low fog, forgot as I was just trying to stay alive with sugar.)

Of course, I was exhausted when I finally came back in range and felt like I’d been hit by a truck. But sure enough, I got up and had a frantic day at the conference centre, in meetings, giving talks and trying to appear functional while feeling absolutely wrecked.

The next day, when I woke up unable to move because I was in pain, I thought that perhaps it was a result of overdoing things the day before, when I should have perhaps taken the morning off to recover from the hypo and the exhaustion that came with it. But of course I didn’t. Because when have I ever taken time off for diabetes? One time I had an evening black out hypo in a park requiring paramedic attention and I was in at work at my desk by 8.30am the next day. Because why wouldn’t I be? My weird and illogical attitude is that if I was to take time off to recover every time diabetes doesn’t play nicely, I’d be taking hours off each week. No one has time for that. At least, I certainly don’t.

And how very messed up that thinking is. I realise that. And I know what I say to friends with diabetes who tell me about their particularly crappy hypos, or when diabetes is kicking their arse/ass: ‘Take the time and let your body rest,’ I’ll say. ‘You’ve just been dealt a pretty shitty blow to your body and mind. Don’t overdo it,’ I’ll remind them.

And what do they do? They don’t rest. They don’t listen to their body. They overdo it. It’s what we do.

It’s messed up and we keep doing it, even though we know better. Of course we know better: because we give good advice to others. But we then do that ridiculous thing where we think resilience is strength, where actually, resilience would be listening to what our bodies need and then doing it. We ignore symptoms and give ourselves imaginary gold stars for ‘pushing through’.

It took some weird virus that literally hampered my ability to walk for me to take time off work. Sleeping 20 hours a day was all I could manage. But you know what? I should have slept 20 hours the day after the five-hour low to recover too, but of course I didn’t.

Who am I trying to impress by soldiering on as though there’s nothing wrong? What am I trying to prove? Do I think we get extra points in some bizarre Hunger Games-like challenge? Is it that I worry what others will think of me if I say, ‘I need to stop for a bit’? Am I afraid of seeming weak? Lazy? Or am I – twenty-seven years later – trying to live up to the ‘diabetes doesn’t change anything’ line I was fed the day I was diagnosed, even though it changes everything?

I’ve been back home now for two weeks now and really just getting back to regular programming now. On Sunday I was able to stand up for long enough to bake a cake. That was a win. I also was able to walk to our local café – a five-minute walk away – but needed a lift home. Slowly, but definitely better.

I’m not pushing myself – partly because I can’t, but also because I refuse to and that is something that is very weird for me. I’m home this week instead of flying to Bangkok to speak at the IDF Congress – the first time I have ever cancelled a work trip. Usually I push through. Usually I suck it up and pretend all is fine. Because I drank the ‘diabetes-won’t-stop-me’ Kool Aid when instead, I should have recognised that there is no shame in stopping to rest. I need to be better and do better about this. And listen to the advice I would give everyone else. Permission to take time out for diabetes.

This post is dedicated to my darling friend and #dedoc° colleague Jean who also doesn’t know when to stop. Let this be a reminder to put down the Kool Aid!

When the clock ticked over into 2025, I had no intention of even considering coming up with New Year’s resolutions that would shape my new year. But with all that is going on in the world, I’ve given myself permission to reconsider and do all I can to stick to it. And I’m encouraging everyone I know to make the same resolution.

And that resolution is to do a health literacy check-up and to actively pushback against misinformation. There has never been a time when being health literate is more important. I thought that during the COVID years as we received a daily onslaught of misinformation about vaccines, bogus treatments (bleach, anyone?), outright lies (“it’s just a cold”) and conspiracy theories (“BigVax is behind it all”). But how naïve I was. Those days seems like just a warm-up for what is happening today.

I’m in Australia, but I don’t for one moment think we are immune to the madness sweeping the world. But if you are shaking your head and laughing a little when RFK Jr spews his anti-vax, anti-fluoride, anti-science agenda, or Dr Oz uses his latest pseudoscience claim as the foundation for whatever supplement he is selling, you’re not grasping the seriousness of what is going on. Before we Aussies get too smug, we should remember our own backyard isn’t devoid of charlatans, and it’s only a matter of time before someone like Pete Evans is taken seriously in public health discussions. Think I’m over-reacting? He already made a run for the senate. How long before a conservative party sweeps him into their fold?

I think it’s safe to say that we have moved beyond this sort of misinformation being a fringe issue amongst ‘crunchy’ parents, trad wives and ‘wellness’ influencers. And Gwyneth Paltrow.

Health misinformation is deliberate and it’s mainstream, and protecting yourself against it isn’t optional – it’s essential.

Up until now there have been guardrails in place to protect public health. Boards and regulatory agencies have existed to ensure medical safety and provide us with confidence that there are processes in place to determine the safety of drugs, devices, healthcare programs. Guidelines are based on robust and rigorous research and are developed using evidence and expert consensus. (Side bar: Have people with lived experience been involved in these practises? Absolutely not enough. Could this be better? Absolutely yes.)

Critical thinkers understand that science is not static. We understand that science changes as evidence evolves. We also understand that we don’t have to follow guidelines blindly. We should understand and consider them. And then use them to make informed health choices. I repeatedly say this to anyone who questions off label healthcare (my favourite kind of healthcare!): ‘I understand guidelines and learn the rules so I can break them safely’. That’s what being health literate does – it gives me an understanding of risks and benefits to make decisions about my health and what works best for me. And it gives me confidence to spot and push back on misinformation.

Critical thinkers also know that questioning medical advice is not the same as embracing conspiracy theories. It doesn’t mean throwing the baby out with the bathwater as you hastily reject modern medicine in favour of snake oil salespeople. It certainly doesn’t mean denying the effectiveness of a vaccines. And it doesn’t mean trusting Instagram wellness influencers.

More than ever, now is the time to do some questioning – to question who is spreading health information and consider their motives. What are they selling? (Case in point: Jessie Inchauspe who offensively calls herself ‘Glucose Goddess’ while selling her ridiculous ‘Anti Spike’ rubbish as she spreads fear about perfectly normal glucose fluctuations in people without diabetes). And a question that right now should be front of everyone’s mind: What power grab is behind the way someone is positioning themselves as an oracle of health information?

This post is about health literacy in general, but because this blog is called ‘Diabetogenic’ and I have diabetes, most people reading will be directly impacted by diabetes. And if there is any silver lining in this shitshow, it’s this: We’ve been dealing with health misinformation about our condition for decades, so in some ways, we’re probably ahead of the curve. We’ve had to wade through the myriad cures and magic therapies, the serums and pseudo-therapies. And the cinnamon – so much cinnamon! We’ve been standing up for science, challenging misinformation, and ensuring that diabetes health therapies are based on evidence, not fairytales. We’ve expected truth in our healthcare. It’s seemed the normal thing to do. Now it feels like a radical act to be a critical thinker.

We are a crucial point because health is being weaponised more than ever. Someone told me the other day that my lane is diabetes and health, and I should leave politics out of it. It’s laughable (and terrifying) to think that anyone doesn’t understand that health is political. It always has been. And even more so right now. We are seeing in real time political figures (and rich white men who own electric car companies) weaponise health misinformation for their own agendas, and scarily people are listening to them. They are elevating unqualified voices and aligning with conspiracy theorists, giving dangerous misinformation legitimacy. (And if you think that it’s all eerily familiar, you’re right. It’s already happened with climate change.)

Your radical act is to be smarter, to be more critical, to question sources and motives; follow reputable sources, don’t share viral posts before fact checking (Snopes is super useful here). Don’t reject credible advice and information in favour of conspiracy theories. Stack your bookshelves with books by qualified experts (I’d recommend starting with Jen Gunter’s holy trinity – The Vagina Bible, The Menopause Manifest and Blood and Emma Becket’s You Are More Than What You Eat), including lived experience experts who base their healthcare on legitimate evidence. Follow diabetes organisations like Breakthrough T1D (JDRF in Australia) for research updates and community efforts and be smart about which community-based groups you join. If moderators are not calling out health misinformation, I’d be questioning just how the group is contributing to diabetes wellbeing.

We know knowledge is power. But that knowledge base has to be grounded in fact, not fiction. Health literacy is critical because misinformation isn’t going anywhere, and neither are the people pushing it for profit and power. My resolution is to sharpen my critical thinking skills, ask questions, and refuse to let bad science set us backwards and cast a dark shadow over the health landscape. Who knew something so fundamental could be such a radical act?

Colour me unsurprised they couldn’t back up their claim with evidence.