You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Communication’ category.

I shared this photo to Twitter the other day:

I couldn’t care less if there are diet books on bookshelves at bookshops. Clearly there is a buck to be made with the latest fad diet, and so, diet scammers gonna scam and publishers gonna publish.

What I do care about is the framing that health is limited to weight loss and dieting.

Living with diabetes has the potential to completely screw up the way food, weight and wellbeing coexist. My own disordered thinking has come from a multitude of different sources. I know that even before diabetes I had some pretty messed up ideas about weight loss and my own weight, but once diagnosed all bets were off and that thinking went haywire! I know it didn’t help when, in the days before diagnosis as I was feeling as though I was slowly dying, someone effusively told me how amazing I looked after having lost some weight that I really didn’t ‘need’ to lose. And look at that! A little weight bias in there already as I talk about ‘not ‘needing’ to lose weight’.

I remember that afternoon very clearly. It was Easter Sunday and my whole family was at my grandmother’s house. I’d had a blood test the morning before because I’d gone to my GP with a list of symptoms that these days I know to be ‘The 4 Ts’. (In hindsight, why she didn’t just do a urine check or, capillary blood check, I don’t know.) I was feeling awful and scared. I knew something was wrong, and suspected it was diabetes.

But there I was, literally slumped on the floor against the heater (at my grandmother’s feet) because it was the only place I could feel any warmth at all. Sitting opposite me was a family member who felt the need to tell me how amazing I looked because I’d dropped a few kilos. I could barely see her across the room because my vision was blurry, but hey, someone told me I looked skinny. Wonderful!

That road to further screwing up my thought processes about weight and diabetes was pretty rocky and I was on it. I learnt that thing that we know, but we don’t talk about anywhere enough routinely, and that is that high glucose levels equal weight loss equals compliments about losing weight. (We don’t talk about it because there’s not enough research, but also because in the past a lot of HCPs have gatekept discussions about it because they think that by talking about insulin omission or reduction for weight loss will make people do it. Sure. And sex education for school-aged kids is a bad thing because by NOT talking about sex, teenagers don’t have sex. End sarcasm font.)

It has taken years of working with psychologists to undo that damage – and the damage that diabetes has piled on. I employed simple measures such as stopping stepping on scales and using that measure as a way to determine how ‘good’ I was being. As social media became a part of everyday life, I curated my feeds to ensure I was not bombarded with photos that showed a body type that generally is only achievable when genetics and privilege line up. I learnt to not focus on my own weight and certainly not on other people’s weight, never commenting if someone changed shape. I did all I could to reframe how I felt about different foods, because demonising foods is part of diabetes management.

I was determined to parent in a way that didn’t plant in my daughter’s head the sorts of seeds that had sewn and grown whole crops in my own. While a noble ambition, I realise I was pretty naïve. Sure, we absolutely never talk weight at home, we never have trashy magazines in the house celebrating celebrities’ weight loss or criticising their weight gain. I’ve never uttered the words ‘I feel fat’ in front of my daughter even when I hate absolutely everything I put on my body. Food is never good or bad, and there is no moral judgement associated with what people eat. But the external messaging is relentless and it’s impossible to shield that from anyone. All I could do is provide shelter from it at home and hope for the best.

But despite doing all I can to change my way of thinking and changing my own attitudes and behaviours, it takes a lot of work…and I find myself slipping back into habits and not especially healthy ways of thinking very easily.

Which brings me to my favourite bookshop over the weekend and standing there in front of the health section. I was looking for something to do with health communications, or rather, the way that we frame life with a chronic health condition like diabetes. I wondered if there was anything that spoke not about ‘how to live with a chronic health condition’ but rather ‘how to think with a chronic health condition’. I didn’t want to read more about what to do to fix my body; I wanted to find out how to help focus my mind and love my body. But there was nothing. Nothing at all.

Instead, there were shelves and shelves of books about losing weight, dieting, fasting, ‘cleansing’ (don’t get me started) and then more on fad diets.

When I tweeted the photo, one of my favourite people on Twitter, Dr Emma Beckett (you should follow her for fab fashion and fantastic, fun food facts), mentioned that it is a similar story in the ‘health food’ aisles of the supermarket, where there seems to be a focus on calorie restriction.

How has the idea of being healthy been hijacked by weight loss and diets? How has the idea that restricting our food, limiting nutrients, and shrinking our bodies equates health?

How did we get so screwed up at the notion that thin means healthy; that health has a certain look? Or that dieting means virtue? How is it that when we see diabetes represented that it so often comes down to being about weight loss and controlling what we eat, as if that will solve all the issues that have to do with living with a chronic condition that seeps into every single aspect of our lives?

It takes nothing for those disordered thoughts that are so fucking destructive, thoughts that I have spent so long trying to control and manage and change, to come out from under the covers and start to roar at me. Diabetes success and ‘healthy with diabetes’ seems to have a look and that look is thin. (It’s also white and young.)

Health will never just be about what someone weighs. And yet, we keep perpetuating that myth. I guess that steering away from the health section of bookstores is selfcare for me now. Because as it stands, it just sends me into a massive spin of stress and thinking in a way that is anything but healthy.

NOTE

I work at Diabetes Australia. It is important for me to highlight this because I am writing about a TV show that has not been especially complimentary to that organisation. That is not why I’m writing though. I’m not here to defend or respond to the claims made about

Diabetes Australia. This post is about the way the story of type 2 diabetes is being told in the series.

However, I think that it is important to highlight the lens through which I am watching this show and consider that bias. I think it is also important to consider that my position about stigma, blame and shame and type 2 diabetes has been consistent for a long time.

This post not been reviewed by anyone at Diabetes Australia. As always, my words and thoughts, and mine alone.

___________________________________________

It will come as no surprise to most people that when Diabetes Australia launched a new position statement about type 2 diabetes remission, there was a section on language when speaking about this aspect of type 2 diabetes management. There is also this point: ‘People who do not achieve or sustain remission should not feel that they have ‘failed’.’

Language matters. I wrote about my own concerns about how we talk about type 2 diabetes remission in a post a couple years ago. I am not saying that we shouldn’t be talking about it, or helping people understand what remission is, but I am saying that the way we talk about it must be considered. Because adding more blame and shame to people serves only to further contribute to the burden of living with the condition.

Unfortunately, the same consideration has not been given to a new show on SBS, grandly called ‘Australia’s Health Revolution’. The three-part show is presented by Dr Michael Mosley and exercise physiologist Ray Kelly, with the aim to show that type 2 diabetes remission is achievable with a low-calorie diet. Eight Australians with type 2 diabetes, or pre-diabetes are there as ‘case studies’.

This post is likely to draw criticism from some, and I accept that. But I will point out that it is not actually a commentary on whether remission of type 2 diabetes is achievable or sustainable for people with type 2 diabetes. I am a storyteller and a story listener, and I hear stories from people who say that they have achieved remission and others who haven’t. In the spirit of YDMV, I’m going to say that there is no one size fits all, and that this is a super complex issue.

This post also isn’t a commentary on the struggles some people with type 2 diabetes face when trying to find a HCP who will support them to aim for remission using a low calorie and/or low carb diet. I think that my position on that is abundantly clear – if your HCP isn’t supporting your management decisions, find a new HCP.

What this is about is how a TV show being shown at prime time is presenting type 2 diabetes, and what is being missed.

Michael Mosley is a TV doctor from the UK who has written books about low calories diets. I probably should be wary to say anything that isn’t glowing praise for the good doctor, because last time I dared do that on TV I was fat shamed. Of course, I wrote about it. Read it here. I know people who diligently follow his 5:2 or low-calorie eating plans and say it has greatly helped them and is terrific for their health. To those people, I say ‘Fantastic!’. Finding something that works is a challenge, and if you’ve found that and you are enjoying it and it’s sustainable for you, brilliant. Anything that improves someone’s health and makes them feel better should be celebrated!

I have no comment to make about Michael Mosley’s diets or the fact that he is selling something – books and a subscription diet plan. But I do have a lot to say about the way he is presenting type 2 diabetes. He is treating type 2 diabetes like an amusement park ride. He started in the first episode by sharing that he was going to ‘Put his body on the line eating a ‘fairly typical Australian diet’ … of ultra-processed food, to see if it pushes his blood sugar into the diabetes range.’ He then had baseline bloods and other metrics taken.

The food Michael Mosley claims to be typically Australian bears no resemblance to the foods that I eat, that I grew up eating, that I cook, that any of my friends or family eat. But, unlike Mosely, I’m checking my privilege right here, and acknowledging that living in inner-city Melbourne with the means to buy fresh foods whenever I want or need and having an excellent knowledge of food and health, plus the time to make things from scratch (something I greatly enjoy doing) means that I am in a different situation to many people whose circumstances don’t mirror mine.

I don’t judge what other people eat, and I don’t apply moral judgements to food. I consider what it costs to put food on the table, and food literacy. Plus, I am learning about how we have simply used the term ‘cultural groups’ to point to higher rates of type 2 diabetes in people of certain backgrounds is a lazy, get-out-of-jail-free card that doesn’t examine important factors such as food availability, poverty, education and history.

I understand that while for some people, walking to the local market is easy and affordable shopping, others are at the mercy of what is on the shelves of their local supermarket. It is not as simple as saying stop eating processed foods when, for some people, that is all they have access to, or to tell people to cook for themselves where they have never been taught. These systemic considerations have not been addressed so far in the TV show, and without doing so, only half the story is being told.

And mostly, I understand that there are genetics at play – massively.

These are not excuses. These are factors that need to be mentioned and considered, because without doing so, we are presenting this as a simple, mindless issue and anyone who doesn’t put their type 2 diabetes into remission has only themselves to blame.

Mosley ate his ‘typical’ Aussie diet for three or so weeks and when he had those same checks run to compare against his baseline, he found that his weight had gone up, as had his blood pressure, glucose levels, cholesterol etc.

Now, if you are thinking you have seen all this before and jumped into a time machine and been taken back to 2004, you would be correct. We saw it first in 2004 when Morgan Spurlock entertained us with his documentary, ‘Super Size Me’. And then again in 2015 with Damon Gameau’s film ‘That Sugar Film’. There is nothing new about privileged white men eating the ‘foods of the poor’ and showing that their health has taken a hit.

Michael Mosley then started eating a low-calorie diet to show just how quickly and simply his weight dropped, and other metrics moved back to within target range.

Thankfully, alongside Mosley is Ray Kelly, and I am so, so grateful that he is there, because he leaves the sensationalist schtick behind to focus on the people and their stories, working to help them set achievable goals. He replaces Mosley’s melodramatic with compassion, simplicity with conversations about the complexity of diabetes, and privilege and assumptions with a genuine acknowledgement of the challenges – the social, generational, cultural, psychological challenges – faced by the people with diabetes and prediabetes on the show.

When watching the show last night, my daughter said, ‘Is this like ‘The Biggest Loser’ on SBS?’. I smiled but pointed out that the difference is Ray Kelly. In this show, he is working with Lyn, a woman who is trying to lose weight. Lyn has decided she wants to climb a hill in her area. If it was ‘The Biggest Loser’, they would have tied a truck tire around her waist and made her climb to the top of the hill, with Michelle Bridges screaming at her while she was doing it. But here, Ray marked out the first challenge – a 50 metre there and back walk, to be increased to 75m the next day, knowing every step is one more than the day before.

The big piece missing for me in this television series the absence of any sort of mental health professional (perhaps this will be included in the final episode?). Diabetes is never just about numbers. It’s never just about what we eat, or the medication we take, and it’s never just about what we weigh. Addressing behavioural change must be part of this discussion if change is to be sustained. In an interview he did for the show, Mosley says ‘Anxiety also encourages people to eat more’. And yet, at no point has anxiety or any other mental illness and its impact into type 2 diabetes and obesity been discussed.

Should we be speaking about type 2 diabetes remission? YES! Of course we should, especially as there is a growing body of evidence helping us to understand more and more about it. But we need to be doing it better than we’re seeing here. I don’t know Ray Kelly (expect for a couple of encounters on Twitter), but I feel that his approach is what we need more of. We certainly don’t need sensationalism and blame and shame. And please, we don’t need more stigma.

Last month was the tenth anniversary of Diabetes Australia first launching a position statement about diabetes and language, encouraging everyone – health professionals, researchers, the media and the general public – to be conscious of just how powerful the words used about diabetes can be.

People with diabetes already knew this – we’d been speaking about it for decades. But to have a document supported by research certainly did add some weight to the discussion. It started a global movement and other diabetes organisations and groups have since launched their own guidance statements and documents motivating the use of language that doesn’t shame, blame and stigmatise diabetes.

Today, I’m so delighted to be hosting a panel with some of the people who have been instrumental in elevating and advancing the #LanguageMatters movement all around the world. You can watch from the Diabetes Australia Facebook page – there’s no need to register. And, I’ll share the full video of the Summit on here some time in the next couple of days.

Disclosure

I work at Diabetes Australia. I have been involved in organising this event and will be speaking at it. I’m sharing simply because I’m beyond exited that it’s happening and am hoping to see lots and lots of you there!

When I talk about the highs and lows of diabetes it’s not just the rollercoaster of numbers. I wrote yesterday about feeling a little low and overwhelmed after a particularly gruelling day. Today, however, I’m on an absolute high after a busy night, or rather, early morning, giving two talks at the ISPAD conference.

docday° was a little different this time, in a truly brilliant way. It was the first time that the event was on the scientific program of a conference, meaning that it was easier for conference registrants to attend. Having a program session that is truly led and designed and features PWD, elevates the standing of lived experience.

The docday° program highlighted some of the topics very close to the hearts of many people with diabetes. Emma Doble from BMJ spoke about working closely with the docday°voices team to publish stories written by individual and groups of people with diabetes. How fantastic to see the words and lived experience feature in such a prominent medical journal!

I touched on language and diabetes – the first talk on the topic for the conference for me. Steffi Haack gave a beautiful talk about peer support and touched on what we get from being in a community of others with diabetes can offer. Steffi managed to perfectly capture the essence of what the community can offer, while also discussing why it’s not necessarily perfect. And we finished with Tino – Tinotenda Dzikiti – from Zimbabwe talking about access and affordability of diabetes medications and treatments. Tino has been a standout advocate in the dedoc voices program, and I make sure to take any chance I get to listen to him.

After docday°, I was an invited speaking in the Psychosocial Issues in Diabetes Symposium which involved an incredible panel of speakers including Rose Stewart from the UK and Korey Hood from the US. Rose spoke eloquently about the importance of integrating psychologists into diabetes care teams, and Korey provided some terrific tips about dealing with diabetes burnout. I followed the two of them (not daunting at all…!) to talk about the language matters movement in diabetes, starting with a reminder that we are talking about more than language – and it’s certainly more than just specific words. It’s about communication, attitudes, images used, and behaviours.

The way that I speak about language these days is different. I think that at first, I spent the majority of the time explaining what it was all about. These days, there seems to be enough ‘brand awareness’ in the community about language matters and that means being able to home in on some of the more nuanced aspects of it.

And so, while I still talk about words that I (and from research we’ve done, others) consider problematic (‘compliant’ is the one that I like to highlight), I spend more time talking about the image problem diabetes has, and about the trickle-down effect language has had on shaping that image.

I point out that there are people who think that language is not all that important in the grand scheme of things, and that there are more important things to worry about in the diabetes world and I very much understand that. I also understand that people have different focuses. But when I ask people what those important things are, they include issues such as research for a cure and better treatments, better access, more education. And then I can’t help but see and think about how research is less because of the image problem about diabetes. That treatments and a cure need governments to prioritise diabetes when it comes to their research dollars and individuals need to give generously when there are funding drives.

But because diabetes is seen as something not serious, and that people are to blame for their own health condition, we are not seeing those dollars coming our way.

It never is and it never was about picking on certain words; it has always been about changing attitudes. Because that is what will change diabetes’ image problem.

I am an advisor to the #dedoc° voices program. I do not receive any payment for this role.

As an invited speaker at the #ISPAD2021 annual meeting, I was given complimentary registration for the conference.

I am helping organise the Diabetes Australia Global Language Summit, and will be hosting the panel discussion.

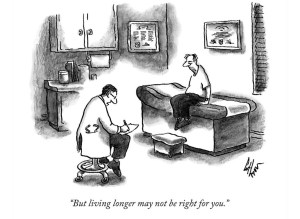

I’m a huge fan of New Yorker cartoons, (clearly – they’re littered throughout this blog!), and the artists that make real life situations come to life using humour, satire and more than a little cynicism.

Sometimes I hoot out loud at the sheer brilliance of what I am seeing. Other times I smile wryly. This time I gasped in absolute shock and horror. And familiarity.

It’s from February 2016, and seems to have been frightfully prophetic for our COVID times. As ‘underlying conditions’ has become barely-concealed code for ‘half dead anyway’, artist, Frank Cotham seems to have had a futuristic glimpse into the 2021 minds of conservative politicians and commentators.

Stay strong, my friends with diabetes and other underlying conditions. You matter. We all do. And living longer absolutely is right for us.

I probably should stop thinking of my job as ‘my new job’. I’ve been at Diabetes Australia now for well over five years. But for some reason, I still think of it that way. And so do a lot of other people who often will ask ‘How’s the new job?’

Well, the new job is great, and I’ve enjoyed the last five years immensely. It’s a very different role to the one I had previously, even though both have been in diabetes organisations.

One thing that is very different is that in my (not) new job I don’t have the day-to-day contact with people with diabetes that I used to have. That’s not to say that I am removed from the lived experience – in fact, in a lot of ways I’m probably more connected now simply because I speak to a far more diverse group of people affected by diabetes. But in my last job, I would often really get to know people because I’d see them at the events my team was running, year in, year out.

Today, I got a call from one of those people. (I have their permission to tell this story now.) They found my contact details through the organisation and gave me a call because they needed a chat. After a long time with diabetes (longer than the 23 years I’ve had diabetes as an annoying companion), they have recently been diagnosed with a diabetes-related complication. The specific complication is irrelevant to this post.

They’ve been struggling with this diagnosis because along with it came a whole lot more. They told me about the stigma they were feeling, to begin with primarily from themselves. ‘Renza,’ they said to me. ‘I feel like a failure. I’ve always been led to believe that diabetes complications happen when we fail our diabetes management. I know it’s not true, but it’s how I feel, and I’ve given myself a hard time because of it.’

That internalised stigma is B.I.G. I hear about it a lot. I’ve spent a long time learning to unpack it and try to not impact how I feel about myself and my diabetes.

The next bit was also all too common. ‘And my diabetes health professionals are disappointed in me. I know they are by the way they are now speaking to me.’

We chatted for a long time, and I suggested some things they might like to look at. I asked if they were still connected to the peer support group they’d once been an integral part of, but after moving suburbs, they’d lost contact with diabetes mates. I pointed out some online resources, and, knowing that they often are involved in online discussions, asked if they’d checked out the #TalkAboutComplications hashtag. They were not familiar with it, and I pointed out just how much information there was on there – especially from others living with diabetes and diabetes-related complications. ‘It’s not completely stigma free,’ I said. ‘But I think you’ll find that it is a really good way to connect with others who might just be able to offer some support.’

They said they’d have a look.

We chatted a bit more and I told them they could call me any time for a chat. I hope they do.

A couple of hours later, my phone beeped with a new text message. It was from this person. They’d read through dozens and dozens of tweets and clicked on links and had even sent a few messages to some people. ‘Why didn’t I know about this before?’, they asked me.

Our community is a treasure trove of support and information, and sometimes I think we forget just how valuable different things are. The #TalkAboutComplications ‘campaign’ was everywhere a couple of years ago, and I heard from so many people that it helped them greatly. I spoke about it – particularly the language aspect of it – in different settings around the world and wrote about it a lot.

While the hashtag may not get used all that much these days, everything is still there. I sent out a tweet today with it, just as a little reminder. All the support, the connections, the advice from people with diabetes is still available. I hope that people who need it today can find it and learn from it. And share it. That’s one of the things this community does well – shares the good stuff, and this is definitely some of the good stuff!

Want more?

Check out the hashtag on Twitter here.

You can watch a presentation from ATTD 2019 here.

Read this article from BMJ.

There are two boxes on my desk today because I am recording a little video for a new series at work. In my diabetes store cupboard, there are lots of boxes from currently using and past diabetes devices and products.

These boxes all contain promises and hope – promises to make diabetes easier and the hope that some of the significant time dedicated to something that no one really wants to dedicate time to is gained back.

Burden is very personal. One person’s significant diabetes burden is another’s mild inconvenience. Some look at a CGM and see life changing and lifesaving technology and others see a nagging device of torture. I vacillate between the two trains of thought.

No diabetes device is perfect and does all things. Most rarely even do what they promise on the box.

And yet when we look online often all we see is the perfect stuff. With diabetes tech companies getting smart and becoming all social media savvy, they have looked to the community to see how we communicate and share. It’s not a silly thing to do. Many of the decisions I’ve made about diabetes tech choices have been based on what my peers have to say. But I’m selective about who I search for when looking for those personal experiences and testimonials. I look either for people I kind of know, or people who have a history of being open and honest and real about their experience.

I’d make a lousy ambassador, even though I am asked almost daily to either become an ambassador for a company or promote their product, with lots of free stuff thrown in. Some offer payments. Sometimes I agree to try something, but there are never any strings attached, and while I will accept the product, I will never be paid for using it, or for writing about it. (You can see that in my disclaimers when talking about product. I always say that I’m sharing because I want, not because it’s part of the arrangement for me to use gifted or discounted product. I’ve never done that.) That’s not to say that I have not had arrangements with different companies and been paid an honorarium for my time and expertise, but that is always in the capacity of being an advisor, or consultant.

I’m too honest about the challenges of different diabetes technologies – you bet I love Dtech, but not everything about all of it! It’s why I am always wary of anyone spruiking any diabetes product who has only positive things to say. In the last 20 years, I’ve used or tried pumps from Medtronic, Cozmo, Animas, Roche and Ypsomed. I have loved them all. And hated them all. I’ve never had only good things to say about any of them – even the Cozmo which remains my favourite ever pump, and anytime I see one, I have strong happy feelings of nostalgia…but despite that, it still had its failings that I spoke about often when I used it.

I’ve used CGM products from Medtronic, Dexcom and Libre and had few good things to say about some generations, better things to say about others, but never loved every single aspect of any of them. Because there is always something that isn’t perfect, or even almost perfect.

And finally, I’ve used countless blood glucose monitors from every brand in Australia and some I’ve picked up on travels, and it’s the same deal: love some things, drop the f bomb about others.

The times I have been gifted products, I have always been honest when talking about them, highlighting the pros and cons. Even though I always write about the positives and negatives, I’ve always urged people to read or listen to whatever I have to say understanding that there is a lens of bias with which I see them through. Of course there is, and others should consider that. I also know I have never consented to having anything I’ve said or written reviewed or amended by the company who has kindly gifted product, or have I promised to do a certain number of posts or tweets or Insta pics about them. The sharing I do is always on my terms as are the words in those shares.

I have, however seen many contracts these days that are very prescriptive when it comes to the expectations and commitments of the people being given product. I don’t have an issue with that; I couldn’t care less really. But I don’t think that simply putting the words #Ad on a post gives people the true picture behind the arrangement in place, which is important for the reader if they are to consider just what bias could be at play when reading someone’s opinions.

I am always pleased when I see that industry is engaging with PWD. There should be clear lines of communication, and hearing what PWD say is critical – far more so, in my mind, than what the shiny brochures have to say. But just as I read what the company’s PR messaging has to say with some scepticism, I do the same when I am not clear of the pact between the company and the PWD.

Diabetes devices rarely, in fact, I’d go so far as to say NEVER, do all that they promise on the box. I think I’ve known that all along, but it wasn’t until I started using something that doesn’t come boxed up in sparkly, fancy packaging that I truly realised just how much that wasn’t true.

Those promises to do less diabetes – to reduce that burden – was only ever true to a small degree. And sometimes, there was added burden that you could only truly learn about if you knew where and how to access others with diabetes, in particular those that didn’t sound as though they were simply regurgitating what the brochures said.

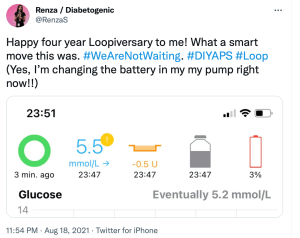

Using an out of the box diabetes tech solution isn’t all perfect. There are somethings about DIYAPS that annoy me. A red loop on my Loop app can be frustrating – even if it’s a simple fix. Needing to carry around an OrangeLink and making sure it’s in range gets irritating. Not having a dedicated 1800 number that I can call 24/7 and handing over any concerns to someone else means that the troubleshooting burden falls squarely on my shoulders – even if there is a community out there to help me through.

And yet, even with all that, it is the first time ever that I have been able to say that I do less diabetes. How much less? Well, I think that Justin Walker’s assessment from a presentation at Diabetes Mine’s DData event back in 2018 is right. He said that using a DIYAPS has given him back an hour a day where he no longer needs to think about diabetes.

Last week, I hit four years of Looping. That’s 1,460 hours I’ve clawed back. Or over 60 days. If DIYAPS came in a box (and with a PR machine and marketing materials) and it promised me that, I wouldn’t believe it based on previous experience. But I guess that’s the thing. There is no box, there is no marketing juggernaut. It’s just the stories of people with diabetes who have worked through this and worked it out for themselves.

An out of the box marketing solution for an out of the box diabetes technology solution. I’ve never trusted anything more.

Often when we talk or read about technology it is very much about the latest, newest, shiniest devices. And yes, I wrote about those last week. There’s nothing wrong with learning about latest tech releases, or desperately wanting to get your hands on them.

But the devices are only ever half the story. And that’s why it was so great to see that in amongst all the data and the new things, was a presentation that reminded everyone watching the technology symposium at ADC that the data belongs to people and the devices are worn on the bodies of those people.

This is the whole warm hands, cool tech concept that is often missing when we hear about technology. The devices are not inanimate, they need human interaction to make them work for … well … for humans.

I despair at some of the stories we hear about technology and people with diabetes. Some talk experiences that have left them feeling like a failure when the tech has simply not been right for them. Because that is the way it is posed. If we decide the tech doesn’t suit us, hasn’t worked for us, hasn’t helped us achieve our goals, we’ve failed it.

The truth is, it’s more likely that the failure – if we need to frame it that way – is not the PWD at all. It’s more likely that the tech is not right for the person, and there wasn’t enough assistance to help navigate through to choose the right tech. Or the education was insufficient, or not tailored for the PWD, or not interesting, or not relevant (more on that soon, from Dr Bill Polonsky’s opening plenary from the conference). It is possible that the timing wasn’t right, the circumstances were not optimal, not enough conversations about cost or effort required … whatever it is, none of the blame for something not being right should be placed on the PWD.

When we look at diabetes education, or engagement with healthcare professionals, the stories that are celebrations or considered successes (from the perspective of the PWD and, hopefully, the HCP) show the right recipe. The ingredients will all be different, but the method seems to be the same: the person with diabetes is listened too, time is taken to understand what is important for them, the PWD’s priorities are clear, and goals are realistic and checked along the way. The end results are not necessarily based on numbers or data points, but rather, just how well the person with diabetes is feeling about their diabetes, and if anything new has added to their daily burden. Reviews are focused on successes more than anything else.

My favourite ever diabetes educator, Cheryl Steele, gave an outstanding presentation on how HCPs can best work with people with diabetes to ensure we get the most from our technology.

I spoke with Cheryl after her talk (you can watch the video of our chat for Diabetes Australia at the end of today’s post), and she laughingly said that she could have said the most important things she wanted to say in 2 minutes, and with one slide that basically just said that HCPs need to be truly person-centred and listen to PWD.

But thankfully, she spoke a lot more than that and covered a number of different topics. But the thing that got to me – and the thing that I hope the predominantly HCP audience would take home and remember – was Chery urging her colleagues to focus on the positives.

Cheryl said, ‘The emphasis has to be on what you’re doing well’ and I feel that is a wonderful place to start and end healthcare consultations. I think about experiences where that has happened to me. Such as the time I went to my ophthalmologist after a few years of missing appointments and his reaction to seeing me was not to tell me off for not showing up previously, but instead to welcome me and say it was great I was there. I’ve never missed an appointment since.

How many PWD reading this have stories to share of times when they went into an appointment with data and all that was focused on was the out-of-range numbers? There are countless stories in online diabetes groups where HCPs have concentrated on the 10% out of range numbers rather than the 90% in range. Actually, even if only 10% of numbers were in range, that is 10% that are bang where they need to be!

Perhaps that’s what’s missing from diabetes appointments. Gold stars and elephant stamps!

There is something devastating about walking into an appointment and the first, and sometimes only, thing that is on the HCPs radar is numbers that are below or above the PWD’s target glucose range. I’ve sat in those appointments. I know the feeling of walking in and feeling that I’m tracking okay, only to have none of the hard work I’ve managed acknowledged and instead, only the difficulties addressed.

But then, I think about one of the first experiences with the endocrinologist I have been seeing for twenty years. Without judgement, she acknowledged that I wasn’t checking my glucose much, and asked if I felt that I could start to do one check every Wednesday morning when I woke up. I said that it seemed like such a pathetic goal to set, but she gently said, ‘One is more than none’. The focus was not on what I wasn’t achieving. It was on what I could.

What a wonderful motivator that is.

Disclosures

Thanks to the Australian Diabetes Society and Australian Diabetes Educators Association, organisers of the Australasian Diabetes Congress for complimentary registration to attend the conference. This gave me access to all the sessions.

I work for Diabetes Australia and the video shared is part of the organisations Facebook Live series. I am sharing here because is relevant to this post, not because I have been asked to.

As usual, no one has reviewed this piece before I hit publish (which is unfortunate because I could really do with an editor).

A week out from National Diabetes Week, and this piece has been sitting in my ‘to be published’ folder, just waiting. But the post-NDW exhaustion coupled with lockdown exhaustion, plus wanting to make sure that all my thoughts are lined up have meant that I haven’t hit the go button.

In the lead up to NDW I wrote this piece for the Diabetes Australia website. That piece was a mea culpa, acknowledging my own contribution to diabetes-related stigma and owning it. I also stand by my thoughts that the stigma from within the community is very real and does happen.

But what I didn’t address is just where that stigma comes from. Those biases that many people with type 1 diabetes (and those directly affected by it) have towards type 2 diabetes come from somewhere, and in a lot of cases that is the same place where the general community’s bias about diabetes comes from. It is all very well for us to expect people with type 1 diabetes to do better, but I’m not sure that is necessarily fair. I think that we should have the same expectations of everyone when it comes to stamping out stigma.

And so, to the source of stigma and, as I’ve said before, it comes from lots of places. As someone who has spent the last twenty years working in diabetes organisations, I know that the messaging my orgs like (and including) those that have paid my weekly salary has been problematic. I still am haunted by the ‘scary’ campaign from a few years ago that involved spiders, clowns, and sharks. (If you don’t remember that campaign, good. If you do, therapy works.)

For me personally, I don’t think much stigma I have faced has come at the hands of other PWD. Sure, there’s the low carb nutters who seem to have featured far too frequently on my stigma radar, however, the most common source of stigma has undoubtedly been HCPs.

It’s not just me who has had this experience. The majority of what I have seen online as a response to experiences about stigma involves heartbreaking tales of PWDs’ encounters with their HCPs.

While I will call out nastiness at every corner, and no stigma is good stigma, it must be said that there is a particular harm that comes when the origin of the stigma is the very people charged to help us. Walking into a health professional appointment feeling overwhelmed, scared, and frustrated only to leave still feeling those things, but with added judgement, shame and guilt is detrimental to any endeavours to live well with diabetes. In fact, the most likely outcome of repeated, or even singular, experiences like that is to simply not go back. And who could criticise that reaction, really? Why would anyone continually put themselves in a situation where they feel that way? I wouldn’t. I know that because I didn’t.

It’s one thing to see a crappy joke from a comedian who thinks they’re being brilliantly original (they never are) or the mundane, and almost expected, ‘diabetes on a plate’ throwaway line in a cooking show, but while these incidents can be damaging, they are very different to having stigmatising comments and behaviours directed at an individual as is often the case when it is from a HCP.

Of course, HCPs aren’t immune to the bias that forms negative ideas and opinions about diabetes. In the same way that people with type 1 diabetes form these biases because those misconceptions are prevalent in the community, HCPs see them too. Remember this slide that I shared from a conference presentation?

This came from student nurses. Just think about that. Students who were training to be HCPs who would inevitably be working with people with diabetes. A I wrote at the time:

‘They hadn’t even set foot on the wards yet as qualified HCPs. But somehow, their perceptions of people with diabetes were already negative, and so full of bias. Already, they have a seed planted that is going to grow into a huge tree of blaming and shaming. And the people they are trusted to help will be made to feel at fault and as though they deserve whatever comes their way.’

Is it any wonder that, with these attitudes seemingly welded on, that people with diabetes are experience stigma at the hands of their HCPs?

The impetus can’t only be on PWD to call this out. And the calls to fix stigma can’t exclusively rest on the shoulders of PWD – we already have a lot of weight there! It must come from HCPs as well – especially as there is such a problem with this group. Perhaps the first step is to see real acknowledgement from this group of their role here – a mea culpa from professional bodies and individuals alike. Recognising that no one is immune to the bias is a good step. Owning that bias is another. And then doing something about it – something meaningful – is how we make things better for people with diabetes. I really hope we see that happening.

More about this:

Becoming an ally – how HCPs can show they’re really on our side.