Edwin Pascoe, who works as a registered nurse and credentialled diabetes educator, has explored the uniqueness of sexual orientation (gay) among men with type 2 diabetes in his PhD thesis with Victoria University.

This is Edwin’s second post for Diabetogenic (read the first one here).

This weekend, the Mid-summa Pride March marks its 25th year of the LGBTQIA+ community and this year diabetes will be represented. Edwin invites you to participate and march in what appears to be the first-time diabetes has been represented at such an event in the world.

To get involved in this historic event and support LGBTQIA+ people with diabetes, please contact Edwin Pascoe on diabetes-education@hotmail.com.

But first, read Edwin’s post.

They say that you can’t really know what it’s like to experience a particular-group of people’s world, unless you have been there yourself. The reason is that your vantage point restricts your line of sight. You only get to see certain things and while people can explain these things to you, their gravity may remain elusive.

This line of sight is often further obscured by well-meaning comments directed at members of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Asexual, Intersex plus (LGBTQIA+)

community, such as ‘aren’t we all the same’, which are often offered up when a person makes that leap of faith to come out as non-heterosexual to their health care practitioner.

In a sense LGBTQIA+ people are shut down in these conversations by such comments and blended into some kind of homogenised one size fits all approach: a far cry from patient centred care. To put it crudely, it’s nice not to stick out like dogs’ balls but there are times when its important, and even pivotal to explain your truth when speaking about matters as important as your health.

However, the influences among LGBTQIA+ people are so subtle and varied that they escape detection, by even the people who are affected by them – these are often described as incognizant social influences.

For many, the idea of sexual orientation having an influence on diabetes management does not make sense, so when this idea is challenged cognitive dissonance comes into play.

Cognitive dissonance is an internal psychological self-talk that serve to maintain some sort of order when beliefs are inconsistent. Internal beliefs shared by many HCPs are:

- They treat all patients equally

- Being gay (sexual orientation) is about sex practices, hence the word sexual orientation.

- Psychosocial factors influence people’s management of diabetes and so need to be considered in diabetes education.

However, these 3 factors clash and have, to this date, resulted in silence when it comes to talking about sexual orientation and diabetes as evidenced by a lack of research in the diabetes space within Australia and indeed the world. Silence, however, only serves to further perpetuate this silence.

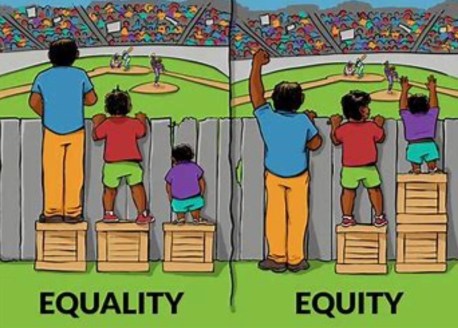

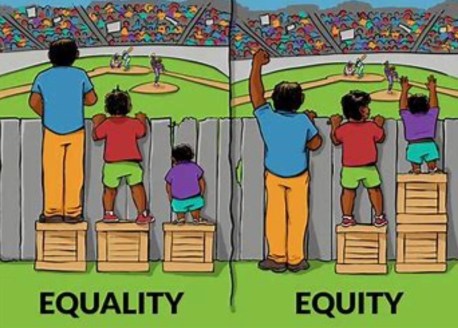

While point 3 is true, point 1 and 2 may not be the case. In point 1, many people in my study expressed that they treat all people the same which is probably true, but does that mean the people they care for receive equitable care or equal chance of access? Review this famous picture which makes it abundantly clear that we must do different things to achieve the same outcome.

There are myriad psychosocial factors that are unique to LGBTQIA+ people with diabetes, e.g. homophobia in sport, eating disorders such as binge eating disorder found to be at higher rates in gay men and stress (including depression and anxiety) and stress related behaviour (smoking, drugs e.g. amyl nitrate effecting eye health, alcohol).

Likewise support structures among gay men are generally quite different. For straight people their family will often be there to support them when required (e.g. taking them to an appointment, motivating them to take medicines and monitor or seek help and assisting them in an emergency.) For LGBTQAI+ seeking support can be problematic as they may be estranged from their family to varying degrees; provision by religious groups are absent for many gay men; and they may disengage from the gay community if they don’t meet image ideals that can exist.

Loneliness and isolation is a problem in the LGBTQIA+ community. In point 2, the belief that the discussion of ‘gay’ is synonymous with a discussion of sex, is quite pervasive but only represents one aspect of a person’s life. This obsession with sex of gay men has been represented in a multiplicity of discourses, from different powerful institutions in society throughout history like law, religion and medicine, that have directed that conversation, including endocrinology.

A German doctor by the name of Eugen Steinach in the speciality of endocrinology performed orchidectomies on gay males in the 1920s and transplanted them with those of straight males, in the belief that homosexual tendencies were rooted in the testicles. Various barbaric gay conversion practices were carried out up until recently; while time-lines are unclear due to wide spread secrecy, we know homosexuality was removed as a mental illness in 1992 in the WHO ICD classification system.

However, 28 years on, the legacy effect of this cruel regime remains ever present in medicine as reported by various Australian studies and case reports of homophobia. There is a paucity of education within healthcare on matters of LGBQIA+ people and this is in part leading to ongoing ignorance.

In addition to this specialisation within medicine has meant that those who are well informed on LGBTQIA+ issues are usually far removed from mainstream medicine e.g. sexual health and mental health clinics, meaning possibilities for mentoring by colleagues and upskilling is reduced.

Again, LGBTQIA+ remain invisible as we don’t tend to record this information due to sensitivities around this topic. Generally, we use labels to denote difference but leave them out if they are part of the ‘norm’. This is problematic as the so-called norm is that which other things are compared to, while those labelled are counted as second to the norm – but at least they are counted. However even more frightful are those that don’t receive the reward of that label – they are the invisible.

To put it in religious terms we could refer to this last group as the dammed. Therefore, it is those of the ‘norm’ that get to decide who gets counted and who do not. For example, we talk about women in cricket, why? to denote they exist and are unique as compared to the norm which are men. However, what would it mean if we didn’t label women in cricket? Would it render them invisible and we didn’t get to see their contribution? We don’t say men in cricket.

It is common to talk about men in nursing to denote they bring a difference to nursing, normally a female dominated profession. Of course, these labels are artificial but speak to power of words in healthcare and why LANGUAGE MATTERS.

Sexual orientation labels are however judiciously applied in medicine as there is a lot of anxiety around this. Anxiety arises from HCP who fear causing offence and LGBQIA+ people themselves who fear discrimination by HCP. Anxiety is often attributed to the sexual factors and as such attempt to adjust this medical gaze must be challenged and adjusted to above the waist to encapsulate the entire person because maybe only then, the laser sharp focus on sex and the judgment that goes with this may start to dissipate? It doesn’t mean we forget sex but that this only becomes part of the whole. This is important, as both the sexual practices and the non-sexual practices of people contribute to health in diabetes.

Sexual health education in diabetes for all people e.g. male, female, LGBTQIA+ and HIV is presently only rudimentary and for some non-existent. Our sensitivities in this are harming people with diabetes.

Straight people are spared the need to come out with a label as this is the norm. They have the freedom to flow casually into and out of conversations which encapsulate topics such as relationships and sex, which gay men must first censor or even disguise if it means coming out, if they want an answer to their question.

While the topics such as erectile dysfunction may be similar between gay and straight men, the psychosocial context of these are different which HCP must be attuned to if they are to develop a therapeutic relationship, but are they? While it is clear that there are some homophobic HCPs out there, for the most it’s a lack of awareness and nervousness about how to navigate this field.

Although it’s unclear why, in my study, gay men with type 2 diabetes attended allied health services 50% less than the general population in Australia e.g. diabetes educators, dieticians and endocrinologist. In addition to this those who didn’t attend, displayed an increase in complications and a trend towards glucose levels outside the range. This highlights 2 things here, one is that multidisciplinary care works and secondly that gay men disengage from these services that can help. Allied health needs to explore ways to better engage LGBTQIA+ people through education and further research.

It’s great that a number of PWD already know that they will be part of ATTD this year, attending satellite events run by different device and drug companies. Some are on the program and some will be there through other opportunities and work.

It’s great that a number of PWD already know that they will be part of ATTD this year, attending satellite events run by different device and drug companies. Some are on the program and some will be there through other opportunities and work.