You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Real life’ category.

Every morning for the last few months, my husband has posted a Facebook update on Victoria’s COVID numbers, along with a cheery message of congrats and motivation for fellow Victorians, in particular Melburnians.

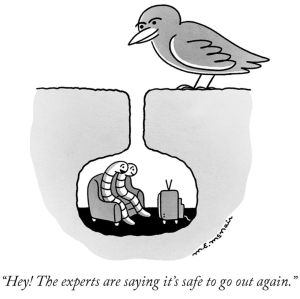

My beautiful city has emerged from a long winter, spent very much not only indoors, but also within a 5km confine of our homes. The lockdown that saw us absolutely smash our second wave of COVID-19 was tough, but clearly necessary to regain control of numbers that were starting to look very, very scary.

I struggled with a lot of what was going on during that time. I am so lucky that the cocoon in which I live felt safe and secure and happy, because there was a lot going on that was not like that.

I had to stop watching the daily pressers from our Premier, not because the numbers were too overwhelming, (although the days we peaked at 700 new cases a day were tough), but rather because the media’s approach to just how present the information became too difficult to watch.

I’d already been stressed with reporting of those of us deemed high risk. That sense that we were disposable and didn’t matter with the dismissive ‘It’s nothing unless you’re old and already sick’, was a recurring theme from the moment the pandemic started.

But now it was more than that. It was the relentless negativity that was being thrown at the Premier and the Chief Health Officer that became unbearable. I realised that once I could recognise the voices and knew the names of the Murdoch hacks that hijacked the daily updates with their attempted gotcha-questions, that those who were meant to be reporting the news had become the news. I’m sure that’s not what journalists are meant to do.

Our whole state was desperately trying to understand just what was going on and how safe or at risk we were, but the loudest corners of the media seemed more focused on trying to bait politicians into admitting that they are the devil.

The same went for the way that opposition politicians who instead of being voices of support for their constituents, hampered, undermined and outright sabotaged the public health efforts that were clearly working.

This constant stream of negativity was impacting my mental health more than any curfew, needing to wear a mask, or limit to being permitted out of the house.

I also had to turn away and stop engaging completely with COVIDIOTS and conspiracy theorists who were outdoing each other with their stupidity. I still am incredulous that ‘anti-maskers’ is a thing. Except I’m not, because most of them are also anti-vaxers, and I’m pretty sure there is a direct correlation between the two. And so, I started using the mute function deliberately. Words, phrases and people that fed my anxieties because of their fear mongering were suddenly silent, and amazingly, I saw how much better I started to feel.

What I realised is that it comes down to this: in times when things are difficult and overwhelming, the fuel that keeps us going is not anger and negativity.

I am an annoyingly positive person by nature. It drives people around me nuts sometimes as I try to find the upbeat spin to pretty much everything. It wasn’t always easy during our long lockdown, but I tried.

Those daily number updates from my husband were really not about the numbers – most mornings I’d fed him the stats because I was the one tuned to Twitter until the DHHS daily update. It was the way he was sharing the news. I turned to him one morning and said ‘You’re like a cheer squad for Victoria. It’s lovely!’ I wasn’t the only one. Many people commented on how they waited for his injection of sunshine to get their day started.

Luckily for Aaron, he wasn’t the only person I was relying on for that positivity. On days where worries about diabetes-ing during a pandemic were creeping into my mind, I turned to friends in the diabetes community – both IRL and online. But again, I got smarter about how I did that. I completely isolated myself from whole corners of the DOC – again using mute – and found that my new curated DOC provided a source of support, entertainment and decent information. It’s amazing how much nicer one’s feed is without the passive aggressiveness and sub-tweeting that is just so common. (And yes, that last sentence could be considered an example of said shitty behaviour!)

The message group of my squad of four diabetes friends in particular lightened the load considerably, and helped talk me down from ledges of feeling scared and overwhelmed, with a mixture of reassuring messages, updates from their parts of the world, goofy animal pictures, sweary-ness and general inappropriateness, and a level of understanding that helped me breathe freely again.

I wonder what I’ll remember in years to come when I think back to 2020. I don’t think it will be the crappy media and sabotaging politicians. I know it probably won’t be diabetes because apart from occasionally heightened anxiety about the intersection of diabetes and COVID-19, my diabetes was manageable.

I suspect it will be the people around me – both physically and virtually – who made this dark time a little brighter. It will be my tightknit bubble of family and friends. It will be those friends who sent ridiculous memes, and made me laugh. The friends who shared pics of what they were cooking or book recommendations or how they cleverly were keeping their kids entertained while distance learning was happening. It will be the people who reached out as soon as Melbourne went into lockdown to ask how we were coping.

And so, now as there is so much more light here in Melbourne (both literally and figuratively) I’m keeping all of this close. Who knows where this pandemic will take us, or if there is a third wave coming? But if there is, perhaps I’ll feel better prepared, and know what to do.

The OPEN Diabetes Project is currently running a survey to look at the impact of do-it-yourself artificial pancreas systems (DIYAPS) on the health and wellbeing of users. There are stories all over the DOC about how people with diabetes (and parents of kids with diabetes) have taken the leap to Loop. These stories provide wonderful anecdotal tales of just why and how this tech has helped people.

The idea behind this new survey from the OPEN Diabetes team is to continue to build evidence about the effectiveness of this technology as well as take a look into the future to see just what this tech could have in store.

And important part of this new study is that it is not only OPEN (see what I did there?) to people who are using DIYAPS. That means anyone with diabetes can participate.

This project is important on a number of levels. It was conceived by people with diabetes and a significant number of the people involved in the project team (and I am one of them) are living with diabetes. We very much live the day-to-day life of diabetes and that certainly does make a difference when thinking about research. Also critically important is the fact that the ACBRD has recently joined the OPEN Project consortium. Having a team of researchers exclusively looking at the behavioural impact of diabetes technology will offer insights that have not necessarily been previously considered in such a robust way.

All the information you need can be found by clicking on the image below – including who to speak with if you are looking for more information. Please share the link to the survey with any of your diabetes networks, healthcare professionals who can help pass on details and anyone else who may be able to help spread the word.

A reminder – this is open to everyone with diabetes – not just people using DIYAPS. (I’m stating that again because it may not be all that clear as you are reading through the material once you click through to the survey.) You do not need to be Looping or ever tried the technology. Anyone with any type of diabetes, or parents/carers of kids with diabetes can be involved.

DISCLSOURE

Over the weekend, an embargoed press release arrived in my inbox with a few different pieces of research that would be presented in coming days at EASD.

Being registered as press for diabetes conferences means getting an advance peek into some of the big stories that are likely to generate a lot of interest and discussion. This email offered three or four pieces of research, but it was the first one listed in the subject heading that made me catch my breath and hesitate on the button to read the email beyond the header,

Shorter. Life. Expectancy.

The three words ran through my mind over and over before I steeled myself enough to open the email and read the release, then the abstract and finally the full article. As confronting as the email header was, there was nothing in there that I didn’t expect, and nothing really that surprised me. It’s not new news. I remember being told early into my diagnosis that I could expect to live 15 years less because of diabetes; something I casually announced to my sister one night when we were out for dinner. Through tears, she made me promise to never say that again, and I just hope she’s not reading this right now.

But even though there was nothing in there that made me feel especially concerned, I did bristle at the conclusion of the article, in particular this:

‘Linking poor glycaemic control to expected mortality … may incentivise … people with diabetes and poor control to increase their efforts to achieve targets.’

I’m ignoring the language here, because even more problematic than the specific words in here is the sentiment which I read as ‘scare people and threaten them with early death to try harder’. Unsurprisingly, I find that horrendous. Equally horrendous is the assumption that people are not already trying as hard as they possibly can. It’s not possible to increase efforts if someone is already putting in the maximum.

Over the last twenty-two years, my diabetes management has sat at pretty much every single data point along the ‘glycaemic control’ spectrum, from A1Cs in the 4s and 5s all the way up to the mid-teens. There is no way that being told that I was going to die earlier would have made me pull up my socks to do better. In fact, it’s likely that if anyone had, at any point (but especially when I was sitting way above target), told me that I was sending myself to an early grave, all that would have done was send me further into the depressive burnout hole I was already cowering in.

It’s tough going knowing that the health condition that I’m doing everything in my power to manage as best as I possibly can is going to contribute to cutting my life short; that despite those efforts, I am likely to see fewer years of my daughter’s life and be outlived by most of my friends. Placing any of the blame for that on me for that makes me feel even worse.

I’m not here to argue with the article – it was an analysis of an audit of data out of England. I’m not here to say that this sort of information shouldn’t be shared, because of course it should be. Understanding outcomes, what drives them, interventions that can help and any other factor that provides better results for people with diabetes is a brilliant thing. These sorts of results could be used to highlight when and how to intensify and prioritise treatment options.

I do, however, question the way that the information will be used. Also, from the article:

‘Communication of life years lost from now to patients at the time of consultation with healthcare professionals and through messages publicised by advocacy groups … and … national/international patient facing organisations will be of great help in terms of disseminations of the conclusions of this study.’

I would be really dismayed if I saw any diabetes organisation using this information in a comms campaign, as I fear it could add concern and trauma to people living with diabetes. I worry about how it could be interpreted by well-meaning loved ones to say, ‘If you don’t start looking after yourself, you’re going to die,’ or something similar.

For the record, one of the other studies highlighted in the email was about hot baths and diabetes. The lowdown on that is having regular hot baths may improve cardiovascular risk factors in people with type 2 diabetes. I’m going to do an n=1 study to see if that also helps people with diabetes.

For more information (all Australian sites):

Spend enough time trawling through social media posts with a #DOC somewhere in the hashtag, and it is inevitable that you will see photos of people’s CGM graphs. Often, it’s PWD getting excited at their flat line graphs because they have managed to stay within range for a certain period of time. Or perhaps it’s to show shock and utter disbelief at loop systems doing all the work. It can be because we won’t to show how we have managed to nail the timing and amount of a bolus, and that usually-difficult to manage food nemesis (hello, rice!), completely avoiding a spike. Or, it could be just because we feel like sharing.

I don’t share my graphs a heap these days, but have in the past. It’s a personal decision as to whether we want to share their data online, and if you do, knock yourself out. Your data, your rules! I understand why some feel that it can be considered not especially helpful for others, setting us up to feel we are failing if we compare. But the conversation sharing can generate is really useful for a lot of people.

Every now and then, a non-PWD will share their libre or CGM trace to show that even those with a perfectly working pancreases are subject to glucose fluctuations. This is done with the intention of support and encouragement and to show that flat lines really are unrealistic. While I’m sure that those sharing glucose graphs of people without diabetes is never done with any malice – in fact, completely the opposite – I believe it is nonetheless problematic, and misses the point.

I get it. It’s a noble goal to try to make PWD feel less negative when we are unable to manage a perfectly flat line at 4.0mmol/l for hours on end. And to also understand that’s not how the body actually works, even when everything is doing what it should be doing.

But it is totally redundant. And downright annoying. And also, completely inconsiderate.

I live with diabetes and am fixated on trying to limit the variation of my glucose levels because I have to. PWD are told that keeping those numbers between 4mmol/l and 8 mmol/l is the goal. And we’re told that when we go outside of those numbers – especially when we go beyond the upper limit, all manner of nasty things will happen to us. That’s what was told to me the day I was diagnosed with diabetes, and repeatedly what I have seen since.

Showing me your graph that just happens without any effort on your part is not reassuring. It’s pointless. And somewhat heartless. When your level goes up to 12 because you ate a family block of chocolate, it comes back in-range fairly quickly. And not because you had to do any fancy-pants calculations, or micro (or rage) boluses.

When I eat a block of chocolate, whatever happens next is pretty much 100% due to my efforts. I have done some fancy pants calculations. I have had to bolus – maybe once, most likely a number of times – to get my glucose level back in range. And then I sit there and hope that I haven’t over bolused…

Oh – and when you show me that your glucose levels dipped into the low range or sat there for a while, it doesn’t reassure me or make me feel ‘normal’. Because the difference is that when that happens to me, I am doing all I can to make sure that I am okay, that I don’t pass out, that I don’t overtreat (again!), and that I am safe. And then I get to recover from a hypo hangover – something you are fortunate to never experience.

To be honest, I actually find it completely ironic when it is HCPs sharing their data to make me feel better, and a little thoughtless because the reason that I am in constant pursuit of these straight, tightly-in range lines is because it is HCPs that told me in the first place that is where I must stay to ‘prevent’ all.the.nasty.things.

And finally, when this happens, it centres people without diabetes in a conversation that should very much have the spotlight firmly shone on us. Your glucose level data, and the patterns they make are not like ours. They do not represent the blood, sweat and tears, the emotional turmoil, the frustration, the fear that that is somehow reflected in our data.

Perhaps rather than sharing non-PWD data, instead acknowledge just how difficult it is to do diabetes, and commend people with diabetes for showing up, day after day, to do the best we can – regardless the shape of our CGM graph.

A real-life PWD CGM graph. Mine, from about 10 minutes ago.

As details of the coronavirus pandemic started to be revealed, the message for people with pre-existing chronic health conditions wasn’t good. It became apparent pretty early on that we were in the ‘at risk’ group. When the ‘only the elderly and those with health conditions need to worry’ lines were trotted out on every forum imaginable, many people with diabetes worried, because we were part of that ‘only’.

And so, people with or affected by diabetes tried to collect the best information about how to keep ourselves safe. One of the most common topics of discussion in diabetes online discussion groups, was about seeing diabetes healthcare professionals. Was it safe? Should we go? What about flu shots? And HbA1c checks? As telehealth services popped up, some were relieved, others were confused. Some people felt they didn’t want to be a burden on their HCP, and indeed the health system that we were told was about to be inundated and overwhelmed. Some diabetes clinics were suspended, only taking appointments for urgent matters.

Last week, Monash University released a report that showed that people with diabetes are not seeing their GP at the same rate as this time last year. The development of diabetes care plans is down my two thirds, and diabetes screening is down by one third.

I was interviewed for a television news story yesterday about these finding. Before agreeing to be the case study, I contacted the reporter to get an idea of just how the story was going to be pitched. ‘We’ll be highlighting the findings of the report, how there are concerns now that there will be an influx of people with diabetes needing to see their doctors in coming months, and how it is understandable that people may be anxious about exposure to coronavirus if they do go to the doctor, and therefore are cancelling, postponing or not making appointments at the moment.’ She paused before finishing with, ‘We’re not blaming people at all.’

They were the magic words I needed to hear and gave her our address, after informing her that the interview would have to take place on the front veranda or in the garden because we were not accepting visitors into our house still.

The under two-minute new story was pretty factual and outlined details of the study. (The grab from me they used had me explaining how I had made the decision to postpone my annual eye screening by a few weeks, rather than the appointments that I had still decided to keep such as my flu jab and telehealth appointments). But overall, it was a good story – factual and definitely not blaming.

Sunday afternoon at the (home) office.

And so, perhaps I was feeling a false sense of safety when I read a newspaper report today that mentioned the study. Speaking about the fallout from people not seeing their GP during the pandemic, a doctor quoted in the story said:

‘The last thing we want is a tsunami of serious health issues and worsening chronic conditions coming after this virus, simply because people have stopped taking care of themselves or consulting their GP.’

I read that, re-read it and then couldn’t get past these nine words:

Simply. Because. People. Have. Stopped. Taking. Care. Of. Themselves.

How could a health professional think this about people living with chronic health conditions at any time, but even more so, how could they think that during the confusion and anxiety of living through a global pandemic where outcomes for those same people are likely to be worse?

People may not be going to see their GP, but it is not in defiance or because they have made the wilful decision to stop taking care of themselves. In fact, I honestly don’t know of anyone who has ever made that decision – pandemic or not.

Delaying my eye appointment isn’t an example of me not looking after myself. It is a reflection of the real anxiety I am feeling about exposure to coronavirus – anxiety that became heightened last week when restrictions were eased, and then only got worse again when I heard the news about deaths of people with diabetes. And I know I am not the only person who is feeling the way I am at this time.

And any other time that I have been accused of ‘not taking care of myself’, I was doing the absolute best I could in that moment, considering all the other things that were going on in my life. And yet, it took me a long time to find a diabetes healthcare professional who acknowledged that when I am not in the right place to be managing my diabetes, we first need to start through those other things first. She never blamed me. She just helped me through.

A health professional making the comment that people not attending appointments are ‘not taking care of themselves’ is actually a much bigger problem than just when looked at in the context of COVID-19. It happens all the time.

Stop blaming people with diabetes. Just stop the blame. Stop blaming people if they don’t get diagnosed early. Stop blaming us if we develop complications. Stop blaming us if we develop complications that didn’t get diagnosed early. Stop blaming us for not caring for ourselves.

But then, I guess, it won’t be quite so easy for HCPs to wash their hands of any responsibility they may have for the health outcomes of people with diabetes if, instead of pointing fingers, they hold a mirror up for a moment.

By the weekend, after last Friday’s post expressing the terror I felt reading headlines regarding death rates, diabetes and COVID-19, I’d moved from scared and sad to angry. Diabetes reports in the media are always fraught, and this was no exception.

I took to Twitter, because it’s as good a place as any to scream into the void and lighten my chest from what was weighing heavily on it. You can read that thread here. Or you can just keep reading this post. I wrote about the processes that I have been involved in for getting a story about research from the lab/researcher’s desk out into the general sphere.

So today, I am going to address a number of different stakeholder groups with some ideas for your consideration.

To communication and media teams writing media releases about diabetes research:

I know that you want your story in the press. Many of you have KPIs to meet, and measures of success are how frequently you get a headline in a well-known publication. I know that you often are the ones trying to make dry numbers and statistics compelling enough to get the attention of health writers and journalists.

But please, please don’t tell half stories. Don’t only present the scary stuff without an explanation of how/what that means. And when you provide explanatory information in the hope that the journo you’re pitching to will pick up your story and run, don’t revert to lazy, over-simplistic explanations that have the potential to stigmatise people with diabetes.

To health writers and journalists:

You have a tough job. I get that. Pages need to be filled, angles found and content that will grab the attention of a news-hungry public must be written. But remember, if you are writing about diabetes, it is highly likely that a lot of people reading what you write are people affected by diabetes. Your words are personal to us. When you talk about ‘diabetics dying’, we see ourselves or our loved ones. Please write with sympathy and consideration. Don’t use language that stigmatises. Don’t use words that make the people you are writing about feel hopeless or expendable. Don’t forget that we are real people and we are scared. Are your words going to scare us more?

To anyone asked to comment from an ‘expert’ perspective. (I am not referring to PWD asked to comment from a lived-experience perspective here, because no one gets to tell you how to talk about how you are feeling. Tone policing PWD is never okay, especially when it comes to having a chance to explain how your emotional wellbeing is going…)

Thank you for trying to break down what it is that is being discussed into a way that makes sense to the masses. If you are asked to be the expert quoted in a media release, ask to see drafts and the final version of the release before it goes out. Consider how your words can be used in an article. It’s unlikely that you will be called for clarification of what you have said, or to elaborate, so be clear, concise, non-stigmatising and factual. Also, and I say this delicately, this isn’t about you. You are providing commentary from a professional perspective on a news story about the people who this IS about . The fallout may be tough, and the topic may be contentious, people may not like what you say, but when that becomes a focus, the story shifts away from the people who really matter here. I am begging you to not do that.

I am frequently asked to provide comment for media releases, sometimes as a spokesperson for the organisation where I work, other times from a lived experience perspective. I always insist on seeing the final draft of the release. And yes, this has been my practise since I was burnt with a quote I’d approved being used out of context and painting my response in a different light to how it was intended. I also insist on seeing the words that will be used to describe me. For me personally, that means no use of the words such as suffered, diabetic, victim, but as PWD we can choose those words to suit ourselves.

I am also more than happy to be the bolshy advocate who clearly lays out my expectations about overall language used. I send out language position statements. I know that comms, media and writers don’t always appreciate this, but I don’t really care. It’s my health condition they are writing about, and the readers will not be as nuanced about those affected with diabetes. If they see something, they take it at face value. I want that value to be accurate and non-judgemental!

And finally, a point on language (because, of course I am going here). Many pieces that have been written in the last week have dehumanised diabetes, and people with diabetes.

Words such as fatalities, patients, sufferers, diabetics, ‘the dead’ have all been used to describe the same thing: people with diabetes who have lost their lives. Break that down even further and more simplistically to this: PEOPLE. People who had friends and family and colleagues and pets. People who had lives and loves and who meant something to others and to themselves.

I refuse to reduce the #LanguageMatters movement to the diabetic/person with diabetes debate, but here…here I think it is actually critical. Because perhaps if ‘people with diabetes’ was used by the media (as language position statements around the world suggest), it might be a little more difficult to divorce from the idea that those numbers, those data, those stats being written about are actually about PEOPLE! (Of course, PWD – call yourself whatever you want. Because: your diabetes, your rules and #LanguageMatters to us in different ways.)

People. That’s the starting, middle and end point here. Every single person with diabetes deserves to be written and spoken about in a way that is respectful. Those who have lost their lives to this terrible virus shouldn’t be reduced to numbers. Data and statistics are important in helping us understand what is going on and how to shape our response, but not at the expense of the people…

Yesterday, my little vlog touching on how I was feeling about re-entry into some aspects of real life, and the incremental reduction of restrictions was just a few thoughts that I wanted to talk about.

Today, as we’re learning and seeing more about what we have in store for the coming weeks, that low-level anxiety I mused about, has somehow manifested into a monster.

I think that my overall nervousness and anxiety about COVID-19 has been managed and manageable (albeit with an occasional meltdown). Perhaps that is because I started limiting my interactions early, working from home before lockdowns were announced. I was ahead of the curve (bloody curves – it’s all about curves!) when it came to minimising contact and outings. In fact, after I got back from Madrid back at the end of February, social engagements and general being out and about were really quite scarce.

This sense of control seemed to really help me. I felt confident that I was doing all I could to reduce my risk significantly. And then, once the restrictions were announced, it wasn’t just up to me to control my environment – it was being controlled for me. I didn’t need to worry so much about what Aaron and the kid were being exposed to because they were home. My limited exposure became theirs, and that just made me feel a whole lot better.

We didn’t completely isolate. But we made very deliberate choices about what we would do. As I mentioned in yesterday’s vlog, our local café has a service window to order and collect coffee. I felt safe getting my daily caffeine hit because I could remain safely distant from others and not need to touch door handles (or anything else other than a takeaway coffee cup) or breathe the same indoor air as strangers! When that café had a couple of well-deserved days off for their staff, we went to another one nearby. Once. I walked in and there were too many people inside, standing too close, talking too much. I ordered and waited for my coffee outside (why wasn’t everyone doing that?). And didn’t return.

Visits to the supermarket have been sporadic with my spidey senses on high alert. I’m so conscious of how close other people are, what they have touched and what I touched, what they are doing. I get in and out as fast as I can.

This has all become the norm and I don’t know how to move forward. I don’t know what the baby steps look like that would make me feel comfortable. We still have another two weeks before schools starts to return and our little cocoon is compromised by things outside our control. Yesterday, the kid asked me if it would be okay for her to go back to school once that was announced and would I be concerned because

I really hate feeling vulnerable. And that is exactly how I feel right now.

And torn. I feel torn. I miss my family and friends. I am desperate to be able to get back out and be around them and just not worry. But equally… I don’t know where they’ve been! I don’t trust people – which is a terrible thing to say…

So, what is it? Why do I feel this way? I know I’m not alone. I’ve spoken to some of my friends with diabetes from across the globe and many are saying the same thing. Maybe it’s all that talk that was so, so prominent at the beginning of the outbreak, and has continued as a whisper throughout it about high risk populations. While it made me feel overwhelmed at the beginning, now it is actually scaring me. That vulnerability is completely out of my control and combined with less control over my environment, I feel as though I am spiralling.

I know that I can’t stay all cosied up in my home forever more. I know that my family needs to get back out there; that I need to get back out there. But it is going to take a lot before I feel ready. And even more before I feel comfortable.