You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Real life’ category.

Do you remember life before diabetes? It’s getting harder and harder for me to. I had 24 years without diabetes, and occasionally, I’ll look at a photo from the BD years and think about how much simpler my days were.

Today, I’m wondering how much I remember diabetes before I started using automated insulin delivery (AID). It’s been eight years. Eight years of Loop. Happy loopiversary to me! Diabetes BL (before Loop) felt heavier. And scarier. I remember those months just after I started looping and how different things felt. I remember the better sleep and the increased energy. I remember a lightness that I hadn’t experienced since I was diagnosed.

That’s now my “diabetes normal”. Life with Loop is simply easier than life BL. On the very rare occasions I’ve had to DIY diabetes, it’s been a jolt as I’ve realised just how truly bad I am at diabetes. Embarrassingly bad.

While there was a stark difference back then between people who were using DIYAPS and those who were using interoperable devices on the market, today that difference is less. AID systems are not just for people who choose to build one for themselves. These days, it’s so great to know that there are commercial systems available which means more people have access to AID. We can debate which algorithm is better or whether a commercial or an open-source system is better, but I think that’s a little pointless. If people are doing less diabetes and feeling happier, better and less burdened, it doesn’t matter what they’re using. Your diabetes; your rules!

Eight years on, and despite there being commercial systems I could access, I’ve decided to keep using Loop – the same system I started on 8 years ago. The changes I’ve made are the devices with which I am using Loop. My pink Medtronic pump has been retired, along with the Orange Link (which was obviously in a pink case). Instead, I now use Omnipod, a single device instead of two which has further simplified my diabetes. It’s also meant not worrying about a working back up Medtronic pump, and it means carrying less bulky supplies when travelling.

These may all seem like little things, but they add up.

My decision to not move to a commercial system has been based on a couple of different reasons. I always said that I wouldn’t move to something that required a trade-off whereby any of the convenience of Loop was compromised. I’ve been blousing from my iPhone or Apple watch since 2017, and I refused to let that go. In my mind, having to wrangle my pump from my bra or carry an additional PDM to bolus was a step backwards. Of course, this is now available on some commercial systems, and it’s been super cool to see diabetes friends have access to something that does make diabetes a little less intrusive.

The customisability of Loop has meant that my target levels are set by me and me alone. The lower limit on commercial systems is not what I like mine set at. I wasn’t prepared to sacrifice the flexibility of personalised settings fora one-size-fits-all approach.

I do understand that there are pros to having a commercial system. Having helplines to trouble shoot and customer support on call is certainly a positive. Knowing that an annual Loop rebuild (always anxiety inducing because …well, technology?) is upcoming is stressful. And the worry that the update will break something that’s been working perfectly.

And yet, measure for measure, the decision to continue to use Loop has been very easy.

I still thank the magicians behind open-source technologies for their brilliance and generosity every single day. I’m grateful for the algorithm developers, the people who have written step by step instructions that even I can follow, and I am so thankful for the people who have tried to make devices more affordable. I believe that device makers do genuinely want to make diabetes simpler and help ease the load of diabetes. But in my mind, it’s undeniable that user-led developments have been more successful in actually making diabetes easier. These magicians know firsthand just what it means to claw back from diabetes.

In the end, the goal for me has always been clear: I want diabetes to intrude in my life as little as possible, and I will avail myself of anything that helps. It’s why I continue to use an Anubis even though there is no out of pocket cost for G6 transmitters. Using an Anubis means I change my sensor when it’s getting spotty, not when the factory setting insists, and the transmitter last six instead of three months. See? Fewer diabetes tasks. Less diabetes. That’s the whole point. (And it’s also why I’m hesitant about moving to G7)

When I try to quantify how much less diabetes, I just come back to Justin Walker and his presentation at Diabetes Mine’s DData back in 2018 when he said ‘By wearing Open APS, I save myself about an hour a day not doing diabetes’. Eight years down the track, that’s 2,922 hours I’ve gained back. That’s almost 122 days. It may be thirty seconds here, a minute there. But it adds up. And that time is better in my pocket than in diabetes’.

And so, here I am. Eight years on. With diabetes in the background as much as it can be with the tools I have available to me. I still really don’t like diabetes. I still really resent it takes up the time and brain space it does, and I still want a cure for all of us. Damn, we deserve that.

But in the meantime, I’m going to keep leaning into what the community has done for the community and know how lucky I am to benefit from that knowledge and expertise. Never bet against the T1D community. We know exactly what diabetes takes from us every day. And exactly what it takes to give some of it back.

More on my experiences with Loop

That time I scared the hell out of healthcare professionals

What looping on holidays looks like

A list of how Looped changed my diabetes life (and all of it is still relevant today!)

Postscript

As ever, I’m very aware of my privilege. Access to AID is nowhere near where it should be. If we look at the Australian context, insulin pumps remain out of range for so many people with T1D thanks to outdated funding models. Remember the consensus statement developed last year? And beyond our borders, technology access varies significantly. As a diabetes community, we are not all beneficiaries from this tech until every single person with diabetes has access. And that starts with affordable, uninterrupted access to insulin, right through to the most sophisticated AID systems, to preventative treatments, to cell therapies.

Last week I was in Geneva for the 78th World Health Assembly (WHA78). It’s always interesting being at a health event that is not diabetes specific. It means that I get to learn from others working in the broader health space and see how common themes play out in different health conditions.

It’s also useful to see where there are synergies and opportunities to learn from the experiences of other health communities, and my particular focus is always on issues such as language and communications, lived experience and community-led advocacy.

What I was reminded of last week is that is that stigma is not siloed. It permeates across health conditions and is often fuelled by the same problematic assumptions and biases that I am very familiar with in the diabetes landscape.

I eagerly attended a breakfast session titled ‘Better adherence, better control, better health’ presented by the World Heart Federation and sponsored by Servier. I say eagerly, because I was keen to understand just how and why the term ‘adherence’ continues to be the dominant framing when talking about treatment uptake (and medication taking). And I wanted to understand just how this language was acceptable that this was being used so determinately in one health space when it is so unaccepted in others. This was a follow on from the event at the IDF Congress last month and built on the World Heart Foundation’s World Adherence Day.

While the diabetes #LanguageMatters movement is well established, it is by no means the only one pushing back on unhelpful terminology. There has been research into communication and language for a number of health conditions and published guidance statements for other conditions such as HIV, obesity, mental health, and reproductive health, all challenging language that places blame on individuals instead of acknowledging broader systemic barriers.

I want to say from the outset that I believe that the speakers on the panel genuinely care about improving outcomes for people. But words matter as does the meaning behind those words. And when those words are delivered through paternalistic language it sends very contradictory messages. The focus of the event was very much heart conditions, although there was a representative from the IDF on the panel (more about that later). But regardless the health condition, the messaging was stigmatising.

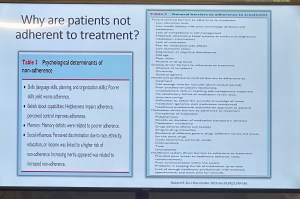

The barriers to people following treatment plans and taking medications as prescribed were clearly outlined by the speakers – and they are not insignificant. In fact, each speaker took time to highlight these barriers and emphasise how substantial they are. I’m wary to share any of the slides because honestly, the language is so problematic, but I am going to share this one because it shows that the speakers were very aware and transparent about the myriad reasons that someone may not be able to start, continue with or consistently follow a treatment plan.

You’ll see that all the usual suspects are there: unaffordable pricing, patchy supply chains, unpleasant side effects, lack of culturally relevant options, varying levels of health literacy and limited engagement from healthcare professionals because working under conditions don’t allow the time they need.

And yet, despite the acknowledgement there is still an air of finger pointing and blaming that accompanies the messaging. This makes absolutely no sense to me. How is it possible to consider personal responsibility as a key reason for lack of engagement with treatment when the reasons are often way beyond the control of the individual?

The question should not be: Why are people not taking their medications? Especially as in so many situations medications are too expensive, not available, too complicated to manage, require unreasonable or inflexible time to take the meds, or come with side effects that significant impact quality of life. Being told to ‘push through’ those side effects without support or alternatives isn’t a solution. It is dismissive and is not in any way person-centred care.

The questions that should be asked are: How do we make meds more affordable, easier to take, and accessible? What are the opportunities to co-design treatment and medication plans with the people who are going to be following them? How do we remove the systemic barriers that make following these plans out of reach?

One of the slides presented showed the percentage people with different chronic conditions not following treatment. Have a look:

My initial thought was not ‘Look at those naughty people not doing what they’re told’. It was this: if 90% of people with a specific condition are not following the prescribed treatment plan, I would suggest – in fact, I did suggest when I took the microphone – the problem is not with the people.

It is with the treatment. Of course it is with the treatment.

The problem with the language of adherence is that it frames outcomes through the lens of personal responsibility. It absolves policy makers of any duty to act and address the structural, economic and systemic barriers that prevent people from accessing and maintaining treatment. Why would they intervene and develop policy if the issue is seen as people being lazy or not committing to their health?

And it means the healthcare professionals are let off the hook. It assumes they are the holders of all knowledge, the giver of treatment and medications, and the person in front of them is there do what they are told.

There is no room in that model for questions, preferences, or complexity. There is no room for lived experience. There are no opportunities for co-design, meaningful engagement or developing plans that are likely to result in better outcomes.

When the room was opened up to questions, I raised these concerns, and the response from the emcee was somewhat dismissive. In fact, she tried to shut me down before I had a chance to make my (short) comment and ask a question. I’ve been in this game long enough to know when to push through, so I did. I also don’t take kindly to anyone shutting down someone with lived experience, especially in a session where our perspective was seriously lacking. Her response was to suggest that diabetes is different. I suggest (actually, I know) she is wrong.

And I will also add: while there was a person with lived experience on the panel, they were given two questions and had minimal space to contribute beyond that. I understand that there were delays that meant they arrived just in time for their session, but they were not included in the list of speakers on the flyer for the event while all the health professionals and those with organisation affiliation were. There comments were at the very end of the session, and I was reminded of this piece I wrote back in 2016 where health blogger and activist Britt Johnson was expected to feel grateful that the emcee, who had ignored her throughout a panel discussion, gave her the last five minutes to contribute.

Collectively this all points to a bigger issue, and we should name that for what it is: tokenism.

I didn’t point this out at the time, but here is a free tip for all health event organisers: getting someone to emcee who is a journalist or on-air reporter does not necessarily a good emcee make. Because when you have someone with a superficial understanding of the nuance and complexity involved in living with a chronic health condition, or understand the power dynamics and sensitivities required when facilitating a conversation about long-term health conditions, you wind up with a presenter who may be able to introduce speakers, but you miss out on meaningful and empathetic framing of the situation. There are people with lived experience who are excellent emcees and moderators, and bring that authenticity to the role. Use them. (Or get someone like Femi Oke who moderated the Helmsley + Access to Medicine Foundation session later in the day. She had obviously done her homework and was absolutely brilliant.)

I know that there has been a lot of attention to language in the diabetes space. But we are not alone. In fact, so much of my understanding has come from the work done by those in the HIV/AIDS community who led the way for language reform. There are also language movements in cancer care, obesity, mental health and more. And even if there are not official guidelines, it takes nothing to listen to community voices to understand how words and communication impact us.

So where to from here? In my comment to the panel, I urged the World Heart Foundation to reconsider the name of their campaign. Rather than framing their activities around adherence, I encouraged them to look for ways to support engagement and work with communities to find a balance in their communications. I asked that they continue to focus on naming the barriers that were outlined in the presentations, and shift from ‘How to we get people to follow?’ to ‘How do we work with people to understand what it is that they can and want to follow?’.

Finally, it was great to see International Diabetes Federation VP Jackie Malouf on the program on the panel. She was there to represent the IDF, but also brought loved experience as the mother of a child with diabetes. The IDF had endorsed World Adherence Day and perhaps had seen some of the public backlash about the campaign and the IDF’s support. Jackie eloquently made the point about how the use of the word was problematic and reinforced stigma and exclusion, and that there needs to be better engagement with the community before continuing with the initiative.

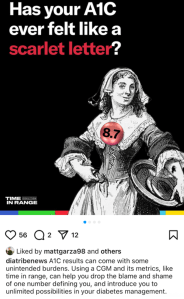

Earlier this week, diaTribe shared this on their Instagram:

It did not sit well with me at all. And I don’t understand the reference to stigma.

A1C is flawed. People with diabetes have been saying this for decades. To have our overall diabetes management measured by an average that gives no nuance to other factors is not a good way to assess health or guide treatment.

CGM changed all that, with visibility into just what is going on with glucose levels at all times. I finally understood why I was so tired some mornings, despite eight solid hours of sleep with in-range numbers at bedtime and at waking. I saw the rollercoaster nights, or the hours at time I was low. It became very clear that my nighttime glucose adventures were exhausting me.

As more people had access to CGM, TIR was heralded as the new gold measuring standard. And it was everywhere. I wrote and spoke about it a lot because the real-time data gave me a clearer understanding of my diabetes. But with that excitement came a gnawing discomfort: were we just swapping out one metric for another?

After a couple of years of TIR, and with the advent of newer, smarter AID systems there was a new kid on the block: Time in Tight Range (TITR). Target upper and lower limits were tightened and there were expectations of remaining within those ranges.

I nodded along because I was, for the most part, comfortably sitting within those number thanks to Loop. And yet, my discomfort grew. More pressure, more expectations on people with diabetes based solely on numbers, and a continued widening of the gap between people with access to tech and those without.

At ATTD a couple of months ago, there was the announcement of a new metric: Time in Normo-Glycaemia – TING! (There is no exclamation mark after the acronym, but it reminds me of the celebratory sound my kitchen timer makes when a cake is done baking, and that deserves festive punctuation.) And horrifyingly, to this #LanguageMatters boffin, the new acronym includes the word ‘normo’. Language position statements have always, always advised against using the word normal/normo. The word shapes attitudes that contribute to stigma. In one study, 85% of PWD surveyed found the word unacceptable.

These measures still focus on one thing: our glucose numbers. There are goals for the percentage of time each day we should be aiming to be in (ever-tightening) range. So, effectively, the HbA1c percentage has been replaced with time in range percentage. It’s still focusing on nothing more than numbers. It still sets us up for a pass/fail framework.

A1C, in itself, is not stigmatising. It’s a number. The language used when discussing A1C can be stigmatising. Attributing success in diabetes to an A1C number can be stigmatising. Being told we’re failing for not reaching an A1C of a certain number is stigmatising. But all of those things are true of TIR.

Before anyone comes at me and tells me that PWD should be able to have numbers within a tight range, of course that’s true. But isn’t that already the goal of our diabetes management? Isn’t that the point with all the glucose measuring, insulin dosing, and considering the bazillion other things we do to manage diabetes? I don’t know anyone with diabetes who does the work with a goal of glucose number of 17.0mmol/l; an HbA1c of 14%; a TIR/TITR/TING of 11%.

But replacing one measure for another still traps us in a numbers-only mindset. How is ‘What’s your TIR?’ really any different to ‘What’s your A1C?’ Does it free us from being metrics-focused? (Some might argue that it ties us to numbers even more with daily updates about how we’re tracking.) Does it address stigma?

I’m not sure it does. I’m not convinced that there is any relevance at all to stigma in this conversation. And I’m a little annoyed at the conflation. Diabetes-related stigma is very topical now, thanks to important efforts by PWD, community groups, researchers and clinicians in the diabetes space. If I was being cynical, I’d suggest that this is an opportunistic attempt to jump on the buzz movement of the moment without meaningfully engaging with what stigma really is or how any type of metric can contribute to it, depending on how it’s framed and used.

Postscript – but possibly the most important part…

And finally, but perhaps most importantly: the very idea that we are suggesting this is the gold standard when it is inaccessible to the vast majority of people with diabetes is just so out of touch. According to the diaTribe article that accompanied the Instagram post I shared earlier, worldwide 9 million people are currently using CGM as part of their diabetes management. The IDF’s latest Atlas data, (launched last month) reports that there are about 589 million adults (20-79 years) with diabetes across the world. That doesn’t include children and young people. (1.8 million young people are estimated to be living with T1D.)

Isn’t this one way stigma takes a hold? When we’re talking about targets that are only available to the small fraction of the diabetes community who can access the tools to achieve them. Setting standards around tech that most can’t obtain doesn’t just ignore reality—it reinforces the stigma of not measuring up.

I’ve been unwell.

And so, I’ve had time to think. Mind you, I’ve found it difficult to form thoughts properly, thanks to the brain fog that is impacting my attention span and ability to think things through to a conclus…oh look! The leaves on the trees in the garden are changing. I should buy the last plums when I go to the fruit and veg shop, and bake a plum cake. That would be delici… Are mandarins in season yet? Ooh, a puppy!

Anyway, back to trying to focus on what I’ve been randomly and messily thinking about.

On my last day at ATTD in Amsterdam, I wound up with a very weird pain flare that meant I could barely move. I put two and two together, came up with the wrong answer and decided it was thanks to arthritis and spent the day before my flight desperately trying to sleep it off so I would be okay to navigate Schiphol Airport and get myself home. I did make it home, but not without wheelchair assistance at each airport, and in excruciating pain for the entire long trip home.

Turns out, it wasn’t arthritis. It also wasn’t diabetes, but that didn’t stop me from trying to connect non-existent dots.

The day before the paralysing pain flare, I woke at 3am with my Dex alarm wailing. I was low. Very low. For five hours. You know, one of those lows that just won’t quit. One of those lows that simply won’t respond to massive quantities of glucose. I ended up throwing up after force feeding myself jellybeans and guzzling juice from the minibar, which was all just lovely. (And yes – I realised I had some inhalable glucagon with me AFTER the fact … but in my low fog, forgot as I was just trying to stay alive with sugar.)

Of course, I was exhausted when I finally came back in range and felt like I’d been hit by a truck. But sure enough, I got up and had a frantic day at the conference centre, in meetings, giving talks and trying to appear functional while feeling absolutely wrecked.

The next day, when I woke up unable to move because I was in pain, I thought that perhaps it was a result of overdoing things the day before, when I should have perhaps taken the morning off to recover from the hypo and the exhaustion that came with it. But of course I didn’t. Because when have I ever taken time off for diabetes? One time I had an evening black out hypo in a park requiring paramedic attention and I was in at work at my desk by 8.30am the next day. Because why wouldn’t I be? My weird and illogical attitude is that if I was to take time off to recover every time diabetes doesn’t play nicely, I’d be taking hours off each week. No one has time for that. At least, I certainly don’t.

And how very messed up that thinking is. I realise that. And I know what I say to friends with diabetes who tell me about their particularly crappy hypos, or when diabetes is kicking their arse/ass: ‘Take the time and let your body rest,’ I’ll say. ‘You’ve just been dealt a pretty shitty blow to your body and mind. Don’t overdo it,’ I’ll remind them.

And what do they do? They don’t rest. They don’t listen to their body. They overdo it. It’s what we do.

It’s messed up and we keep doing it, even though we know better. Of course we know better: because we give good advice to others. But we then do that ridiculous thing where we think resilience is strength, where actually, resilience would be listening to what our bodies need and then doing it. We ignore symptoms and give ourselves imaginary gold stars for ‘pushing through’.

It took some weird virus that literally hampered my ability to walk for me to take time off work. Sleeping 20 hours a day was all I could manage. But you know what? I should have slept 20 hours the day after the five-hour low to recover too, but of course I didn’t.

Who am I trying to impress by soldiering on as though there’s nothing wrong? What am I trying to prove? Do I think we get extra points in some bizarre Hunger Games-like challenge? Is it that I worry what others will think of me if I say, ‘I need to stop for a bit’? Am I afraid of seeming weak? Lazy? Or am I – twenty-seven years later – trying to live up to the ‘diabetes doesn’t change anything’ line I was fed the day I was diagnosed, even though it changes everything?

I’ve been back home now for two weeks now and really just getting back to regular programming now. On Sunday I was able to stand up for long enough to bake a cake. That was a win. I also was able to walk to our local café – a five-minute walk away – but needed a lift home. Slowly, but definitely better.

I’m not pushing myself – partly because I can’t, but also because I refuse to and that is something that is very weird for me. I’m home this week instead of flying to Bangkok to speak at the IDF Congress – the first time I have ever cancelled a work trip. Usually I push through. Usually I suck it up and pretend all is fine. Because I drank the ‘diabetes-won’t-stop-me’ Kool Aid when instead, I should have recognised that there is no shame in stopping to rest. I need to be better and do better about this. And listen to the advice I would give everyone else. Permission to take time out for diabetes.

This post is dedicated to my darling friend and #dedoc° colleague Jean who also doesn’t know when to stop. Let this be a reminder to put down the Kool Aid!

Is it too late to say Happy New Year? Probably, but does anyone actually believe that social norms still exist in the world the way it is these days?

And so – happy New Year to you. I’ve been absent. Not that it’s important to acknowledge this. But I have been because headspace these days is non-existent because of (gesturing wildly) the world.

But anyway, here’s an update no one asked for, (actually not true – thanks to all the people who have reached out and asked):

I made a resolution. Happy to hear that many of you have made a similar one. Smart, smart people!

I also didn’t do things: I didn’t start some bullshit diet, because diet culture sucks and is harmful. I didn’t tell anyone what they should be eating, because no one needs that. I didn’t go away for the holidays, because I was so travel burned out that the last thing I wanted to do was jump on an aeroplane.

Instead, I read some great books (Amor Towles, Jhumpa Lahiri, Paul Auster’s final words) and read some not-so-great books (Stanley Tucci – I adore you, but your latest book could have stayed as a personal diary and not been published, mate). Walked lots. Sat outside in cafes drinking barrel-loads of iced coffee. Saw some movies and binge-watched some TV shows (do we need to talk about Apple Cider Vinegar? Yes, yes we do.)

And I spent a lot of time complaining about my hands. My sore, achy, stiff, stupid hands.

I now have arthritis. Is it because I am old? Or maybe just because I collect health conditions? Is it psoriatic arthritis or is it osteoarthritis? (Probably both.) Does it have anything to do with perimenopause? Is Mercury in retrograde? Did I walk under a ladder? Whatever the reason, it sucks. And it hurts.

This diagnosis actually came last year, so I don’t really get to blame 2025 for it. It started in September. One day, I didn’t have pain in my fingers. And then I did. I spent the whole time I was in NY for the UNGA last year noticing that a lot of the time I moved my index fingers I felt a little twinge. Then the twinge moved to other fingers. By the time I was on the plane home there was pain any time I moved my hands. And even when I didn’t. So pretty much all the time.

These are the hands that type words, make divine cakes and pastries, roll out pasta dough, turn the pages of books, hold onto my loved ones, grasp microphones on conference stages and in media opportunities, press down on cutters as I shape biscuit dough, hold the cups containing the coffee that sees me through the day, doom-scroll through the latest update in the cesspit of the world, tickle the tummies of our dogs, pat the top of the head of our cat, point out the specific pasticcino at the pasticceria I want to eat, stir pots of delicious soups and sugo on the stovetop, tap out snappy responses to misogynists on the internet, are waved around as I talk… And all of these things cause pain. All of them.

Here’s something about me: I don’t deal well with pain. I had a little cry in my GP’s office at the end of last year. I cried because there isn’t something I can do to just fix this. Here’s the list of things I read that I should do to help improve arthritis pain: be a ‘healthy’ weight (because diet culture and we’re led to (falsely) believe that people who live in smaller bodies are always perfectly well. Bullshit), stop smoking, limit alcohol, eat healthily, walk and be active. I can’t start to do those things because I already tick each and every box. So what I am supposed to do? Sure, my activity involves little more than walking, but I do get in close to if not 10,000 steps a day, so I’m not completely sedentary.

I’m whingy about it all because the pain is always there, and I don’t get a break. And diabetes is always there, and I don’t get a break. And anxiety is always there, and I don’t get a break. Honestly, I’d take the pain not being there and keep the others any day.

While I wait to see a rheumatologist, I am doing some things that may be easing the pain a little. I say ‘may’ because I don’t really know, and I don’t want to stop them in case it makes it worse. And I spend a lot of time annoying people by telling them my hands hurt. (Don’t believe me – see the 800 words in this blog post – thanks for reading!)

I know the world doesn’t work this way, but sometimes I think it would be nice if those of us already dealing with a shedload of health conditions could sit things out for a bit. By ‘things’ I mean new diagnoses. That would be fair, wouldn’t it? I don’t really want to add another health professional to my contacts list and dedicate more time in my calendar for regular check-ups. And I don’t want to have to learn the lingo of a new health condition, while training a new HCP to understand the way I like to be treated. I don’t really want to have to give more money to the pharmacist for more drugs. I don’t really want to use more emotional bandwidth worrying and thinking about what this means long term. I don’t want to think about being in pain all the time. I also don’t want to wind up not being able to wear the beautiful rings I own, and feel free to call me shallow while I completely ignore you.

And so, that’s where I am right here and now. A mostly gentle start to the year. And sore hands. Very, very sore hands.

When the clock ticked over into 2025, I had no intention of even considering coming up with New Year’s resolutions that would shape my new year. But with all that is going on in the world, I’ve given myself permission to reconsider and do all I can to stick to it. And I’m encouraging everyone I know to make the same resolution.

And that resolution is to do a health literacy check-up and to actively pushback against misinformation. There has never been a time when being health literate is more important. I thought that during the COVID years as we received a daily onslaught of misinformation about vaccines, bogus treatments (bleach, anyone?), outright lies (“it’s just a cold”) and conspiracy theories (“BigVax is behind it all”). But how naïve I was. Those days seems like just a warm-up for what is happening today.

I’m in Australia, but I don’t for one moment think we are immune to the madness sweeping the world. But if you are shaking your head and laughing a little when RFK Jr spews his anti-vax, anti-fluoride, anti-science agenda, or Dr Oz uses his latest pseudoscience claim as the foundation for whatever supplement he is selling, you’re not grasping the seriousness of what is going on. Before we Aussies get too smug, we should remember our own backyard isn’t devoid of charlatans, and it’s only a matter of time before someone like Pete Evans is taken seriously in public health discussions. Think I’m over-reacting? He already made a run for the senate. How long before a conservative party sweeps him into their fold?

I think it’s safe to say that we have moved beyond this sort of misinformation being a fringe issue amongst ‘crunchy’ parents, trad wives and ‘wellness’ influencers. And Gwyneth Paltrow.

Health misinformation is deliberate and it’s mainstream, and protecting yourself against it isn’t optional – it’s essential.

Up until now there have been guardrails in place to protect public health. Boards and regulatory agencies have existed to ensure medical safety and provide us with confidence that there are processes in place to determine the safety of drugs, devices, healthcare programs. Guidelines are based on robust and rigorous research and are developed using evidence and expert consensus. (Side bar: Have people with lived experience been involved in these practises? Absolutely not enough. Could this be better? Absolutely yes.)

Critical thinkers understand that science is not static. We understand that science changes as evidence evolves. We also understand that we don’t have to follow guidelines blindly. We should understand and consider them. And then use them to make informed health choices. I repeatedly say this to anyone who questions off label healthcare (my favourite kind of healthcare!): ‘I understand guidelines and learn the rules so I can break them safely’. That’s what being health literate does – it gives me an understanding of risks and benefits to make decisions about my health and what works best for me. And it gives me confidence to spot and push back on misinformation.

Critical thinkers also know that questioning medical advice is not the same as embracing conspiracy theories. It doesn’t mean throwing the baby out with the bathwater as you hastily reject modern medicine in favour of snake oil salespeople. It certainly doesn’t mean denying the effectiveness of a vaccines. And it doesn’t mean trusting Instagram wellness influencers.

More than ever, now is the time to do some questioning – to question who is spreading health information and consider their motives. What are they selling? (Case in point: Jessie Inchauspe who offensively calls herself ‘Glucose Goddess’ while selling her ridiculous ‘Anti Spike’ rubbish as she spreads fear about perfectly normal glucose fluctuations in people without diabetes). And a question that right now should be front of everyone’s mind: What power grab is behind the way someone is positioning themselves as an oracle of health information?

This post is about health literacy in general, but because this blog is called ‘Diabetogenic’ and I have diabetes, most people reading will be directly impacted by diabetes. And if there is any silver lining in this shitshow, it’s this: We’ve been dealing with health misinformation about our condition for decades, so in some ways, we’re probably ahead of the curve. We’ve had to wade through the myriad cures and magic therapies, the serums and pseudo-therapies. And the cinnamon – so much cinnamon! We’ve been standing up for science, challenging misinformation, and ensuring that diabetes health therapies are based on evidence, not fairytales. We’ve expected truth in our healthcare. It’s seemed the normal thing to do. Now it feels like a radical act to be a critical thinker.

We are a crucial point because health is being weaponised more than ever. Someone told me the other day that my lane is diabetes and health, and I should leave politics out of it. It’s laughable (and terrifying) to think that anyone doesn’t understand that health is political. It always has been. And even more so right now. We are seeing in real time political figures (and rich white men who own electric car companies) weaponise health misinformation for their own agendas, and scarily people are listening to them. They are elevating unqualified voices and aligning with conspiracy theorists, giving dangerous misinformation legitimacy. (And if you think that it’s all eerily familiar, you’re right. It’s already happened with climate change.)

Your radical act is to be smarter, to be more critical, to question sources and motives; follow reputable sources, don’t share viral posts before fact checking (Snopes is super useful here). Don’t reject credible advice and information in favour of conspiracy theories. Stack your bookshelves with books by qualified experts (I’d recommend starting with Jen Gunter’s holy trinity – The Vagina Bible, The Menopause Manifest and Blood and Emma Becket’s You Are More Than What You Eat), including lived experience experts who base their healthcare on legitimate evidence. Follow diabetes organisations like Breakthrough T1D (JDRF in Australia) for research updates and community efforts and be smart about which community-based groups you join. If moderators are not calling out health misinformation, I’d be questioning just how the group is contributing to diabetes wellbeing.

We know knowledge is power. But that knowledge base has to be grounded in fact, not fiction. Health literacy is critical because misinformation isn’t going anywhere, and neither are the people pushing it for profit and power. My resolution is to sharpen my critical thinking skills, ask questions, and refuse to let bad science set us backwards and cast a dark shadow over the health landscape. Who knew something so fundamental could be such a radical act?

Colour me unsurprised they couldn’t back up their claim with evidence.

So often, there is amazing work being done in the diabetes world that is driven by or involves people with lived experience. Often, this is done in a volunteer capacity – although when we are working with organisations, I hope (and expect) that community members are remunerated for their time and expertise. Of course, there are a lot of organisations also doing some great work – especially those that link closely with people with diabetes through deliberate and meaningful community engagement.

Here are just a few things that involve community members that you can get involved in!

AID access – the time is now!

It’s National Diabetes Week in Australia and if you’ve been following along, you’ll have seen that technology access is very much on the agenda. I’m thrilled that the work I’ve been involved in around AID access (in particular fixing access to insulin pumps in Australia) has gained momentum and put the issue very firmly on the national advocacy agenda, which was one of the aims of the group when we first started working together. Now, we have a Consensus Statement endorsed by community members and all major Australian diabetes organisations, a key recommendation in the recently released Parliamentary Diabetes Inquiry and widening awareness of the issue. But we’re not done – there’s still more to do. Last week I wrote about how now we need the community to continue their involvement and make some noise about the issue. This update provides details of what to do next.

And to quickly show your support, sign the petition here.

Language Matters pregnancy

Earlier this week we saw the launch of a new online survey about the experiences of people with diabetes before, during and after pregnancy, specifically the language and communication used around and to them. Language ALWAYS matters and it doesn’t take much effort to learn from people with diabetes just how much it matters during the especially vulnerable time when pregnancy is on the discussion agenda. And so, this work has been very much powered by community, bringing together lots of people to establish just how people with diabetes can be better supported during this time.

Congratulations to Niki Breslin-Brooker for driving this initiative, and to the team of mainly community members along with HCPs. This has all been done by volunteers, out of hours, in between caring for family, managing work and dealing with diabetes. It’s an honour to work with you all, and a delight to share details of what we’ve been up to!

Have a look at some of the artwork that has been developed to accompany the work. What we know is that it isn’t difficult to make a change that makes a big difference. The phrases you’ll see in the artworks that are being rolled out will be familiar to many people with diabetes. I know I certainly heard most of them back when I was planning for pregnancy – two decades ago. As it turns out, people are still hearing them today. We can, and need to change that!

You can be a part of this important work by filling in this survey which asks for your experiences. It’s for people with diabetes and partners, family members and support people. They survey will be open until the end of September and will inform the next stage of this work – a position statement about language and communication to support people with diabetes.

How do I get involved in research?

One of the things I am frequently asked by PWD is how to learn about and get involved in research studies. Some ideas for Aussies with diabetes: JDRF Australia remains a driving force in type 1 diabetes research across the country, and a quick glance at their website provides a great overview. All trials are neatly located on one page to make it easy to see what’s on the go at the moment and to see if there is anything you can enrol in.

Another great central place to learn about current studies is the Diabetes Technology Research Group website.

ATIC is the Australasian Type 1 Diabetes Immunotherapy Collaboration and is a clinical trials network of adult and paediatric endocrinologists, immunologists, clinical trialists, and members of the T1Dcommunity across Australia and New Zealand, working together to accelerate the development and delivery of immunotherapy treatments for people with type 1 diabetes. More details of current research studies at the centre here.

HypoPAST

HypoPAST stands for Hypoglycaemia Prevention, Awareness of Symptoms and Treatment, and is an innovative online program designed to assist adults with type 1 diabetes in managing their fear of hypoglycaemia. The program focuses on hypoglycaemia prevention, awareness of symptoms, and treatment, offering a comprehensive range of resources, including information, activities, and videos. Study participants access HypoPAST on their computers, tablets, or smartphones.

This study is essential as it harnesses technology to provide practical tools for better diabetes management, addressing a critical need in the diabetes community. By reducing the anxiety associated with hypoglycaemia and improving symptom awareness and treatment strategies, HypoPAST has the potential to enhance the quality of life for individuals with type 1 diabetes.

The study is being conducted by the ACBRD and is currently recruiting participants. It’s almost been fully recruited for, but there are still places. More information here about how to get involved.

Type 1 Screen

Screening for T1D has been very much a focus of scientific conferences this year. At the recent American Diabetes Association Scientific Sessions, screening and information about the stages of T1D were covered in a number of sessions and symposia. Here in Australia. For more details about what’s being done in Australia in this space, check out Type 1 Screen.

And something to read

This article was published in The Lancet earlier in the year, but just sharing here for the first time. The article is about the importance of genuine consumer and community involvement in diabetes care, emphasising the benefits and challenges of ensuring diverse and representative participation to meet the community’s needs effectively.

I spend a lot of time thinking a lot about genuine community involvement in diabetes care and how people with diabetes can contribute to that ‘from the inside’. And by ‘inside’ I mean diabetes organisations, industry, healthcare settings and in research. I may be biased, but I think we add something. I’m grateful that others think that too. But not always. Sometimes, our impact is dismissed or minimised, as are the challenges we face when we act in these roles. I don’t speak for anyone else, but in my own personal instance, I start and end as a person with diabetes. I may work for diabetes organisations, have my own health consultancy, and spend a lot of time volunteering in the diabetes world, but what matters at the end of the day and what never leaves me is that I am a person living with diabetes. And I would expect that is how others would regard me too, or at least would remember that. It’s been somewhat shocking this year to see that some people seem to forget that.

Final thoughts…

Recently when I was in New York at Breakthrough T1D headquarters, I realised just how many people there are in the organisation living with the condition. It’s somewhat confronting – in a good way! – to realise that there are so many people with lived experience working with – very much with – the community. And it’s absolutely delightful to be surrounded by people with diabetes at all levels of the organisation – including the CEO. But you don’t have to have diabetes to work in diabetes. Some of the most impactful people I’ve worked with didn’t live with the condition. But being around people with diabetes as much as possible was important to them. It’s really easy to do when people with diabetes are on staff! I first visited the organisation’s office years ago – long before working with them – to give a talk about language and diabetes. One of the things that stood out for me back then was just how integral lived experience was at that organisation. From the hypo station (clearly put together by PWD who knew they would probably need to use the supplies!) to the conversations with the team, community was in the DNA of the place. As staff, I’ve now visited HQs a few times, and I’ve felt that even more keenly. Walking through the office a couple of weeks ago, I saw this on the desk of one of my colleagues and I couldn’t stop laughing when I saw it. IYKYK – and we completely knew!

DISCLOSURES (So many!)

I was part of the group working on the AID Consensus Statement, and the National AID Access Summit that led to the statement.

I am on the team working on the Language Matters Diabetes and Pregnancy initiative.

I was a co-author on the article, Living between two worlds: lessons for community involvement.

I am an investigator on the HypoPAST study.

My contribution to all these initiatives has been voluntary

I am a representative on the ATIC community group, for which I receive a gift voucher honorarium after attending meetings.

I work for Breakthrough T1D (formerly JDRF).

There are different types of burnout. Diabetes burnout, advocacy burnout, and just plain life burnout.

Diabetes burnout rears its ugly head for many of us living with the condition – sometimes starting as diabetes distress before building and building.

Advocacy burnout seems inevitable the more I discuss it with advocate friends. The living with, working in, supporting others with, diabetes becomes a lot. Too much. So much.

And life burnout seems to be inevitable in the fast-paced, never-pause-for-a-breath, always-switched-on lives we live.

When the three collide it’s a triple threat burnout. Welcome to mine.

The white noise hum of diabetes burnout – always there – slowly, but surely had become amplified. It was little things – I was regularly forgetting to bolus when I ate. Not immediately replacing CGM sensors when one fell off. Ignoring making the follow up diabetes appointments I needed to make, the pathology visit I needed to schedule, the supplies stocktake I needed to do to make sure I didn’t run out of anything.

I’ve been hovering on the edges of advocacy burnout for some time and found myself plunged into it earlier in the year dealing with the complexities that played out as I offered my help and support in some volunteer grassroots advocacy here in Australia.

And life burnout suddenly appeared in the form of exhaustion, but an inability to sleep soundly, and a brain fog that I explained away as a perimenopause symptom. Except it was more than that. It was getting to four in the afternoon before realising I’d not eaten a thing all day. And not remembering if I’d showered, or how many days had passed since I last washed my hair. It was a lethargy that gnawed at me all day long.

I focused on plans for a conference in the US, followed by a few days at work headquarters, knowing that it would be a busy and wonderful time, with a lot of interesting work. I could do it. And I did. The conference was excellent. The diabetes advocates there shone so brightly. And every meeting was a huge success.

Smile. Breath. Smile. Breathe.

Until I couldn’t. That moment hit like a tonne of bricks last week.

I’d spent a day in the office at the job I adore, speaking with incredible people doing so much work. I’m inspired daily by the people I work with and learn so much. There were plans set in motion for exciting things to come and I sat in the meeting room I had set myself up in for the day, feeling satisfied and pleased. The workday done, I packed up and stepped out into the street.

And then, a flash, an instant. Suddenly, the pressure bearing down and around on me was so intense and I felt my chest constrict. I struggled to breathe, and my vision blurred. The sounds on the New York streets suddenly seemed to be coming from under layers of concrete, muffled and hushed and yet piercing at the same time. The bright sunlight seared around me, causing me to shield my eyes from the glare.

‘Breathe. Breathe.’ I felt the rising fright of what I know to be a panic attack, and knew I needed to safely just ride it out. ‘Focus. Focus.’ I looked for something I could hold on to. There it was, a small dog, sitting still, staring dotingly at its human seated at an outdoor café, drinking an iced tea. I stood there, slightly hunched over, my arms wrapped around myself, watching this little dog sitting still. I started to count back from 50, getting to 34 before the dog moved, jumping onto its hindlegs, and resting its front paws on its person’s knee.

It was though the crush from the last few months had all converged. I’d tried in small ways to stem it. I limited my time online, muting more terms and accounts that sought to do nothing but argue and inflame. I welcomed the calmness that descended when my Twitter feed was devoid of people yelling about food choices, and when my Instagram feed only showed me the images of my nearest and dearest. I focused my outside of work advocacy efforts to AID access, specifically on the helpers. I threw myself into my job because it allowed me to focus and celebrate the work of others. I amplified the #dedoc° voices and other advocacy to keep my own away from the spotlight. I thought these things worked.

But at that moment, on the streets of lower Manhattan, those attempts didn’t matter or help. ‘But you seemed fine last week,’ said a friend I’d spent time with at ADA a few days earlier. I had been. I was. I thought about how I appear to others. ‘Sometimes, it’s too much. Right now, it’s too much. Forever… it’s too much.’

I felt the uptick in my heartrate. And realised that had been happening constantly. It had happened after the first difficulty with the grassroots advocacy work, and any time I had to face the source of that stress. Sometimes ‘facing’ meant a comment on a LinkedIn post. Sometimes, it meant a somewhat nasty direct message or, even worse, comments that came to me via others. I realised it had happened every time there was some nastiness or other on Twitter. It happened if there was a confrontation of any time around me, even when I wasn’t involved. Anywhere I saw conflict was enough to kickstart an anxiety response.

‘I’m okay’, I said to my friend. And then, ‘It feels too much.’ I felt myself and my mind and the space around me shatter into a million sharp, craggy pieces. And felt my skin being cut against each and every one of those shards.

This is burnout. This is what it feels like. And with it is anxiety and stress and feeling overwhelmed. We all get it to some degree. Diabetes makes it harder. Diabetes advocacy compounds the whole thing even more. Jet lag doesn’t help. Plus there’s a sprinkling of perimenopause over it all. The culmination is a fragility that scares me a bit and leaves me feeling vulnerable. ‘But you seemed fine…’ my friend had said. And I was. Until the burnout took over. And then I wasn’t anymore.

Poo, poop, crap, shit – whatever you want to call it, it’s not really a topic for polite dinner table conversation. So, if you’re at a polite dinner table, bookmark this and come back later. If you’re, say, on a flight to Orlando, stick around. I’m writing this on a flight to Orlando. The topic feels somewhat appropriate, but I digress.

This is the one about bowel cancer screening.

It all started back at the end of last year. I turned fifty and was suddenly on government watch lists for screening different parts of my ageing body. I wrote about my breast cancer screening a couple of months ago. Bowel cancer screening was next. I’m writing about this because I know people around my age have been putting off doing this. I get it. This sort of stuff scares the shit out of people, so I’m writing about my experience and hope that might encourage others to stop avoiding things.

Let me tell you something about the people who run the Australian bowel cancer screening program. They are stalkers. They start by sending you a letter. It’s friendly enough, just a little heads’ up (tails up?) that you should be on the look out for their next correspondence: a bowel cancer screening kit to do in the privacy of your own bathroom. Sure enough, it arrived a couple of weeks later, just as the silly season was in full swing and we were planning a trip to Italy.

The kit sat on my desk for a couple of months, and I kept meaning to do it, but travel, work, life and an utter lack of desire to actually collect samples of my poo meant that the kit taunted me every time I sat at my desk. During that time, I received reminders from the bowel screening program. Eventually, I got my shit together and stopped putting it off.

It was all very easy: you run a swab over your stool (which is sitting in the toilet on a piece of biodegradable, flushable paper) and then shove the whole swab in a little container with fluid and cap it tightly, pop the sample in a zip lock bag and then into a padded envelope. Probably the worst thing about it is that you need to send in two samples, from two different trips to the bathroom meaning you have your sample in your fridge until you next need to take a crap. (Because I’m germ phobic, I wrapped the padded envelop in three more zip lock bags, shoved into a brown paper bag. Totally unnecessary.)

The next day after collecting the second swab, I posted my sample and rewarded myself for being compliant (ha-ha) by having a massage.

About two weeks later, my stalkers friends from the screening program sent me another letter. There was blood in my sample, and I needed to urgently go see my GP. On the same day, my GP started sending me text messages and emails urging me to go see him. Now. Today. I was, of course, panicking because of course this meant THE WORST, even though the screening program letter assured me that in most cases there was nothing to worry about. BUT SEE YOUR GP NOW.

In Australia, we have an awesome public health system, but I decided to go private because it meant that I could see the gastroenterologist my GP referred me to, and I got an appointment within a week. I want to check my privilege here, because this option means there is a co-pay. I don’t know the time frame to see someone in the public system. (My breast cancer screening was all done through the public system and that was super quick, so that may be the case with bowel cancer screening too, but I can’t speak to that.)

The gastroenterologist was delightful. He apologised for being exactly seven minutes late. I laughed in diabetes and with the experience of someone who has spent too many hours in doctors’ waiting rooms told him he was, in fact, early. He looked all of about seventeen years old, but I could tell immediately that this was a doctor who knew his shit. And mine too, based on the report he had in front of him.

This was the sort of consultation that goes perfectly. Sensible questions about diabetes; super clear explanations about what was going to happen, and he did all he could to alleviate my concerns, reiterating what my GP and the screening letter had said – in most cases, a positive result is nothing. But blood in a sample will always trigger follow up, and that means a colonoscopy. He scheduled one for three weeks later. I had it on Monday.

It’s hard to put a positive spin on needing a colonoscopy, but I tried. I told myself that I would be getting an excellent afternoon nap on a Monday, and I could pretend I was a rubbish influencer doing some rubbish detox. After twenty-four hours of colonoscopy prep, I was reassured that I am no rubbish influencer and rubbish detoxes are, well, rubbish.

If you’ve not had a colonoscopy, or not familiar with how the prep works, let me explain: The week before the procedure, I was told to stop eating nuts, seeds, beans and red meat, and aim for a low fibre diet. Two days before, my food choices were limited further to white bread, eggs and grilled, skinless chicken and fish. The morning before, I could have breakfast of white bread and then nothing solid after that. But lots of clear fluids including tea and coffee (no milk), lemonade, apple juice, and jelly (but not red or purple). My mum, ever the Italian mamma, made me chicken broth, strained a million times so it was clear and full of nutrients, and that sustained me while I couldn’t eat.

I started taking the preparation at 4pm the day before the procedure. I mixed the first sachet into a glass of water and drank it down over about 10 minutes. It tasted like a fizzy orange drink. I put on some elastic-wasted trousers (I was warned that I didn’t want to be fiddling around with a belt or buttons), sat down in front of episodes of Grand Designs and waited. ‘You will experience extreme diarrhoea’ said the information leaflet. No shit, Sherlock. (Except, lots of shit. Obviously.) The solution kicked in after about forty-five minutes.

At 8pm, I mixed up the second sachet in a litre of water and drank that over an hour. I spent about six hours all up needing to head to the loo very quickly as everything was flushed out of me. Unpleasant, but exactly what was meant to happen.

By 10pm, I felt that I was going to be okay going to bed without having to keep running to the loo, and I slept through until my alarm went off at 7 the next morning. I made up the final prep sachet (same as the first), skulled it and, fasted from 8am until the procedure at 1pm.

Through it all, my diabetes was perfectly behaved. I increased my glucose target on my AID from 5.0mmol/l to 7.5mmol/l and entered a slightly reduced temp basal. My glucose levels remained steady the whole time. There were a couple of instances when there was an arrow trending down, but nothing that a couple of sips of clear lemonade couldn’t fix.

At midday on Monday, we headed to the hospital for what was an exceptionally positive experience with wonderful encounters the whole way through from the admission staff and all HCPs. I laughed at the amazed reaction from the anaesthetist when I handed him my iPhone with the instructions, ‘Swipe right to see my glucose levels’.

I walked into the procedure room, climbed on the table, chatted with what seemed like a cast of thousands and the next thing I knew, I was in recovery waking up. The gastroenterologist popped by to tell me everything went well. I love that he didn’t bury the lede: ‘Renza, you don’t have cancer. It all went well. There was one polyp that we removed and have sent away for pathology. I’ll call you in a couple of weeks, and you’ll need another colonoscopy in three years’. He commended me on the way I’d diligently followed the prep instructions. Apparently, I can be deliberately compliant!

The anaesthetist came by too, still slightly enthused with my tech and told me that my glucose levels were steady throughout the procedure. Diabetes was the least of my concerns and, as I do daily, I thanked the very clever people behind Open-Source AID for making things just a tiny bit easier.

And so, that’s the tale of my bowel cancer screening and subsequent colonoscopy. Absolutely something I would have preferred to not do, but glad that I did. How lucky we are to have these screening programs! It’s the same equation as with diabetes-related complications screenings: early detection, early treatment, best possible outcomes. Plus, peace of mind that comes with knowing there isn’t anything to worry about right now. And isn’t that a really good thing?

Shit yeah!

Details on this post

Eleven years ago on Mother’s Day, my friend Kerry started something on her socials. Kerry’s mum sadly died when Kerry was just six years old. She doesn’t have a single clear photo of the two of them together. And so, Kerry has urged her mum friends to make sure they take a photo with their kids – a really simple and special way to make sure that memories are recorded. (You can search for #KTPhotoForMum to see some lovely shared posts.)

We’re not short of photos in our household – who is in the age of smart phones? – but I especially love the album that I have of Mother’s Day photos of me and our girl. Seeing her on this day for the last eleven years brings a special feeling of joy.

But there’s another feeling in there that I want to recognise, and that’s how proud I am. Of course I’m proud of her – she’s a marvel (excuse my bias). But I’m talking about hoe I feel about myself as a mother living with diabetes. Because pregnancy and parenting with diabetes is not an easy gig.

I struggle with this sometimes. I don’t want to be defined by being someone’s mum. I achieved a lot before I became a mother and have done plenty in the last (almost) 20 years that I am so very proud of. There’s travel and a career, and media work, lots of published writing and a whole lot of standing on stages talking diabetes advocacy. These are usually the things that I point to when thinking about my achievements. For some reason, I’ve felt it’s diminishing to point to motherhood as an achievement.

But the truth is, that motherhood with diabetes is an achievement and it is defining in some ways. Conceiving, growing a baby, bringing her into this world, and getting her to adulthood is something that carries a huge sense of pride. Because, damn, diabetes made that hard. Every stage of it.

I get it: pregnancy is natural and it’s been happening forever and there are bazillions of people who have done it for a bazillion years, but there is absolutely nothing natural about taking on the role of a human organ. Seriously! It’s hard at the best of times. Being pregnant adds a degree of difficulty that is incomprehensible until you’re in the midst of it. Even today with tools that are far more sophisticated than the basic pump that saw me through my pregnancy, it’s still not easy. (And I utterly recognise how lucky I was at the time having a pump. The women sitting next to me at the Women’s Hospital diabetes & pregnancy clinic on Wednesday mornings who weren’t using a pump were real magicians.)

At that time I was just so in the weeds of dealing with all that came with a diabetes-complicated pregnancy that I never thought what an incredible job I was doing just getting through it. After all when was I meant to cheer myself for the remarkable effort? Was it before or after the 20+ finger prick checks I was doing each day? (CGM wasn’t around then.) Or alongside the complex calculations that I needed to complete before pre-bolusing the right amount of insulin at the exact right time? It certainly wouldn’t have been during the thirty percent of the day I was below target because in those moments, I was too busy worrying about starving my brain (and baby) of oxygen.

And then there was no time after she came along, because babies are all encompassing and take up every moment of the day. And diabetes can also be all encompassing and is incredibly demanding.

I had no time to be a cheerleader for myself because every single part of me was focused on making sure my baby’s elbows were growing properly, and stressing about how any out of range glucose level was harming her growing organs. Any spare brain bandwidth was taken up feeling guilty because I never felt I was doing enough. I felt that I was probably already failing my child. Even though her elbows are beautiful (and her organs seem fine), I still carry that guilt. Almost twenty years later.

These days, as more people with diabetes share their pregnancy and parenting stories, I DO cheer. Every time I hear about chaotic first trimester hypos, and managing glucose levels around second trimester cravings, and third trimester insulin-resistance frustrations, I know they deserve a loud ‘Hurrah!’ and so I cheer. Because look at these amazing people! Look at what they are doing – the work, the emotional rollercoaster, the determined effort they are putting in to keep themselves and their baby safe! Diabetes never plays nice, and for so many, pregnancy is the most difficult time in someone’s diabetes life.

Yesterday morning, I looked at our daughter as we had our Mother’s Day breakfast in the sunshine. Having her is the hardest thing I have ever done – the hardest, the most emotionally challenging, the scariest – but also the absolute best and I am so very proud that I did.

This post is dedicated to my dear friend Kati who I am cheering for every day!