You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Healthcare team’ category.

When I first spoke to my endo about Loop, I wasn’t really all that concerned or nervous. The decision to take my diabetes management in a new direction was mine and mine alone and I knew she would support and work with me. My approach was pretty much the same as when I have changed any aspect of my management, whether it be introducing new tech, a new eating plan or anything else that deviates from the norm.

And after my first post-loop appointment, when she listened to what I was doing and how it was going, her response was brilliant. I guess that after she heard how great I was feeling and how well I was going since looping she realised that this was the best thing for me to do at the moment and she wanted to know how to continue to support me.

But I know that is not the case for everyone and that is especially evident at the moment with more and more people using DIY diabetes technology solutions.

I frequently see discussions online from people who are very apprehensive about an upcoming appointment when they will be telling their HCP that they are Looping. And I have heard stories of HCPs refusing to continue to see people with diabetes who have started using the technology.

This actually isn’t about Loop. At the moment, a lot of the discussion may be about DIY technologies, but actually, this goes far beyond that.

It’s the same as for people who have adopted a LCHF approach to eating and have been told by their HCPs that it is not healthy and they would be better off returning to an evidence-based eating plan.

It is the same as when pumps were new and CGM was new and Libre was new, and HCPs were wary to recommend or encourage their use due to the lack of evidence supporting the technologies.

I am keeping all this in mind as I prepare for a talk I’m giving this weekend for the Victorian branch of the Australian Diabetes Educators Association. I guess I am a little battle-scarred after my talk at ADATS last year, and am being far less cavalier about charging in and extolling the brilliance of Loop. I know that the audience is new to this technology, know little about it, and might be uncomfortable with the idea that I ‘built my own pancreas’. For some, it will be the first time they have ever seen or heard of it.

I’m trying to think of a way to talk about it so that the audience responds positively to the technology rather than the way many responded at ADATS last year.

But I am a little stuck. Because if I stand up there and say that since looping I feel so, so well, have more energy than in forever, am sleeping better than I have in 20 years, feel less anxious about my diabetes and feel safer, don’t have hypos anymore, feel the least diabetes burden ever, and have an A1c that is beautifully in range… and people still question my decision to use the technology, I’m not sure what else I have. I don’t know what more I can say to try to convince the audience just how much this has benefitted me.

The ending I’m looking for in my talk is for the audience to leave feeling interested in the technology and open to the idea of Loop as a possible tool for some of the people with diabetes they see.

But perhaps more than that, it is wanting the HCPs to think about the way they react when someone walks into their rooms, wanting to talk about something different or something new. It’s about being open to new ideas, accepting that the best thing for the PWD is not what the guidelines say, and realising that there is a lot going on out there that is driven by the end user. And perhaps it’s time to really start listening.

Curled up in the comfort of my bed in Melbourne on Saturday night, I was transported to London where I was watching the live stream and live tweets of the Type 1 Diabetes Rise of the Machines event. (You can read details of that here, or by checking out the #T1DRoM Twitter stream.)

When you are not actually there and able to see and gauge the reaction of the audience, it can be easy to misinterpret the vibe of the room. I couldn’t see the faces or body language of the people in the audience, so I wasn’t sure if my response was the same as theirs.

But there are somethings that can’t be missed – especially with a live Twitter feed!

A representative from one of the device companies was speaking about their range of products, one of which is a blinded CGM device*. Immediately, I bristled. His words celebrating the ‘blinded’ nature of the device, ‘There’s no way for you to interfere with it’, did nothing to make me feel more reassured at what he was saying.

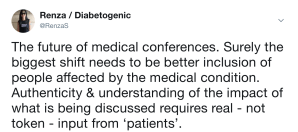

The tweet I sent out pretty much sums up how I felt about his comments:

And this one from Dana Lewis, who was a guest speaker at the event, was bang on:

Yeah – clearly I was not the only one who had that reaction!

I remember a number of years ago wearing a blinded CGM. It was actually the first CGM here in Australia and I was on a trial for something (I actually can’t remember what the trial was for…) and wearing the clunky CGM was part of the study.

But I certainly do remember demanding that once I returned the CGM (after about 3 or 4 days), I was given a print out of my data. ‘Why would you want that?’ the trial nurse asked me. I imagine that the look I gave her could only be described as ‘withering’.

‘Um…so I can see what is going on with my glucose levels throughout the day. That data is gold – there is no way I will ever have seen anything like it before and the insights will be incredibly useful.’

‘But you probably won’t be able to interpret it all. And what are you going to do with the data?’ That question was asked with an element of suspicion.

I don’t suffer fools and was about to yell loudly at the trial nurse who needed some lessons in ‘patient empowerment’, so I decided to take my questions elsewhere, asking to see the trial supervisor who had enrolled me in the study. The result was a crisp envelope with my name neatly printed across the front handed to me at the end of my next visit to the centre.

Fast forward – probably about 17 years – and I wear CGM all the time and use the data to make daily adjustments to my insulin doses. (Well I did until Loop took over that for me. Reason #124978 I love Loop. Have I mentioned that before?)

I can’t imagine having something connected to me that is collecting information that I could use in real time to improve my diabetes management and not be able to access that data. How frustrating it would be to have something attached to me that could tell me when I was going out of range, but not letting me know it at the time so I could actually do something about it!

Today, if a healthcare professional suggested I wear a device for any period of time where I could not access the data there is no way I would agree.

If you think that it is a good idea because not all PWD could understand the information, then that is a shortcoming of the education process – not a shortcoming of the person with diabetes. And, yes, of course not everyone wants to see all their data, but they should certainly have it offered to them if it is out there!

Denying us access to our own data is simply another way of trying to control the narrative of our health condition and our health education. Not arming us with the information – especially if it is readily available – serves no one.

*Blinded devices are often referred to as the ‘Pro’ version which makes me a little annoyed. Pretty sure the ‘Pros’ here are the ones wearing the devices and analysing and acting on the data 24/7…

It’s easy to remember the difficult moments we’ve experienced at the hands of healthcare professionals who have been less than kind.

And, equally, we remember those moments where kindness was shown in spades.

I know I certainly remember moments of kindness in healthcare. And those moments transformed me. I so appreciated the kindness that came from HCPs at moments when a tsunami of grief or despair or pain or a diagnosis washed over me, knocked me to the ground and left me doubtful that I would ever be able to get back up again.

I remember kind words, the silences afforded to me giving me a moment or two (or dozens) to think, the time I was given to understand what was happening and formulate a plan to manage… I remember them all because they left me stronger, more determined, better supported and far more empowered to cope.

Kindness is a highly underrated quality in healthcare. I’m not sure how it should be included in a curriculum full of critically essential information, but it needs to be taught from the very beginning of any healthcare courses, and it’s importance highlighted and stated over and over and over again.

In the last year or so, I’ve read a few books written by (as the publicity often claims) ‘healthcare professionals turned patients’. (I’ve found this to be quite an odd term, because surely everyone at one point or another has been a patient.)

A recurring theme throughout the books is how difficult the HCPs have found it being on the other side of the HCP / patient divide. They often appear astounded at the red tape and bureaucracy they came up against, the hoops they need to jump through to receive the appropriate care, and the sheer unfriendliness of the system. And they write about the extraordinary moments of kindness that often feel far too infrequent.

Sometimes, they have written about how they didn’t realise that the way they themselves behaved could be interpreted as having a lack of consideration and kindness – explaining it was simply their manner and how they made sure they got through the day as efficiently as possible in a system often built on the foundation of complete and utter inefficiency. And yet now…now they understood.

While the books I read have been beautifully written, heart breaking at times, and often end terribly, the stories in them were not surprising. They tell truths about the system – and the lack of kindness – that people with diabetes face every day in every encounter.

When Kate Grainger launched #HelloMyNameIs, she was echoing the calls of countless people before her: please treat us like people. Please tell us what you are doing here. Please know we are scared. Please tell us who you are and what your role in my care will be.

She did it beautifully, simply, eloquently and changed the landscape of healthcare communication. I am so sad that she had to be so ill for this to happen. But her legacy is one for which I am so grateful.

Kindness in healthcare makes all the difference. Some may think it is completely unnecessary and that as long as we are receiving the right diagnosis, good care and excellent treatment, there is nothing more we need. But that is not true. Kindness adds a human element. We need warm hands, warm hearts and warm words alongside the cool tech, sterile environments and scary diagnoses.

Kindness takes no more time; it takes no more effort. But it’s effects can indeed be monumental.

As explained previously, I don’t do new year’s resolutions for the simple reason that I never stick to them. I’m unable to do the whole SMART thing and make my goals actually attainable, and so after the shortest time (a day… an hour… minutes), have thrown in the towel.

However, I am not above making resolutions for others. Because that’s the sort of person I am. Caring and sharing. Or bossy. You decide.

Here are some New Year’s resolutions for HCPs working with people with diabetes to consider:

- Use language that doesn’t stigmatise – both in front of PWD and away from us.

- And while we’re talking words: use words we understand. We may know a lot about our health condition, but we don’t necessarily understand all the medical speak. If you are talking to us, check in to make sure we actually understand what you are saying to us.

- Lose the judgement. We all judge; we do it subconsciously. Try not to.

- Remember who is in charge. While as a HCP you may have a direction that you would like us to take, or our consultations to follow, that might not work for the person with diabetes. Our diabetes; Our rules. Learn the rules and stick to them. (Also, there are not really any rules, so don’t get shitty when we seem to have no idea what we’re doing.)

- Remember this: no one wants to be unhealthy. Or rather, everyone wants to be the healthiest and best they can be. Use this as an underlying principle when meeting people with diabetes.

- Sure, offer help with setting goals. We all like to work towards something. But setting the goal is actually the easy part. Help us work out the steps to get there. If someone comes to you and wants to lose weight or reduce their A1c, that’s awesome, but they are big asks. So, tiny steps, easily achievable mini-goals and rewards for getting there.

- Acknowledge and celebrate victories. You know that person with diabetes sitting opposite you? For some, just getting there and being there is a huge achievement. Recognise that. Showing up with some data – in whatever format? That’s brilliant – so say so. Sure, it may only be three BGL readings from three different meters and all at different times, but that is a start.

- Diabetes is rarely going to be the most important thing in someone’s life. Please don’t ever expect it to be.

- Include us in every discussion about us – from letters to referring doctors or others in our healthcare team and when it comes to any results of bloody checks or scans. Make sure we have copies of these and understand what they all mean.

- Please be realistic. If someone is currently not checking their glucose levels, don’t ask them to suddenly do six checks a day, analyse the data and send you pretty graphs. Small, attainable, reasonable goals. (Once, during a period of particularly brutal burnout when my meter was not seeing the light of day, my endo asked me to do two checks a week: Monday morning before breakfast and Wednesday morning before breakfast. That was it. Next time I went back to see them, I’d not missed a single one of those checks. And even managed to do a few others as well. I felt amazingly good for actually having managed to do what was suggested and eager to keep going from there.)

- Ask us if we want to be pushed a little. Are we interested in new technologies to try, different meds to consider, a more aggressive treatment plan? Don’t assume you know the answer. Present us with the options and then help us decide if it’s something we want to try.

- Equally, if we’re pushing you because we want something new or more intensive, help us get it, learn about it and support our decision to try it.

- Do not dismiss peer networks and peer support. Offer it, direct us to it, encourage us to find it.

- Be on our side. We need champions, not critics. We need people to cheer us on from the sidelines, go into bat for us when we need an advocate and take over the baton when we’ve done all we can (and shit yeah! – that’s three sports analogies in one dot point – I deserve a gold medal!)

- Understand that diabetes does not start and end with our glucose levels. There is so much going on in our head and sometimes we need to be able to get that sorted before we can even begin to think about anything else. Get to know some diabetes-friendly psychologists, social workers and counsellors, and suggest we see them.

- Please, please, please, when it is time for our appointment, do nothing but be there with us. Of course interruptions may happen, but do apologise and excuse yourself – and do everything possible to minimise them. Look at us, take notes on a piece of paper – not a computer, and listen to us.

- Again…listen to us.

- Explain to us why you feel we need to have something done. It could be as simple as asking us to step on the scales (which often is actually not simple, but fraught) or it could be asking us to have a scary-sounding and invasive procedure. Why are you suggesting this? Is this the only course of action?

- Treat us like a person, not our faulty body part. And see all of us – not just our missing islet cells. Because really, if all you are seeing is those missing islet cells, you really are not seeing anything at all.

I wrote this post on this day last year and today, when it came up in my TimeHop app reread it and realised it is a good one to consider at the beginning of the year as I’m trying to get myself in order. I’ve made some edits to some of the points due to changes I made last year in the way I manage my diabetes. (The original post can be found here.)

I suppose that I was reminded that being good at diabetes – something I’m afraid I miss the mark on completely quite often – does involve others who sometimes don’t necessarily understand what it is that I really need. And I can’t be annoyed if they don’t intrinsically know what I want and need if I can’t articulate it. This post was my attempt to do just that.

______________

Sometimes, I’m a lousy person with diabetes (PWD). I am thoughtless and unclear about what I need, have ridiculous expectations of others – and myself, and am lazy. But I’m not always like that. And I think I know what I need to do to be better.

Being a better PWD is about being true to myself. It is also about reflecting on exactly what I need and I hope to get it.

- I need to remember that diabetes is not going away

- I need to remember that the here and now is just as important as the future

- I need to remember that I don’t have to like diabetes, but I have to do diabetes

- I need to remember that the diabetes support teams around me really only have my best interest at heart, and to go easy on them when I am feeling crap

- I need to empty my bag of used glucose strips more frequently to stop the strip glitter effect that follows me wherever I go – edit: while this is true, I do have to admit to having far fewer strips in my bag these days due to my rather lax calibration technique

- I need to remember that it is not anyone else’s job to understand what living with my brand of diabetes is all about

- I need to remember that the frustrating and tiresome nature of diabetes is part of the deal

- I need to be better at changing my pump line regularly – edit: even more so now that I am Looping and think about diabetes less than before.

- I need my diabetes tasks to be more meaningful – quit the diabetes ennui and make smarter decisions

- And I need to own those decisions

- I need to see my endocrinologist – edit: actually, this one I managed to nail last year and even have an appointment booked in for a couple of months’ time!

- I need to decide what I want to do with my current diabetes technology. There is nothing new coming onto the market that I want, but what about a DIY project to try something new? #OpenAPS anyone…? – edit: oh yeah. I started Looping….

- Or, I need to work out how to convince the people at TSlim to launch their pump here in Australia – edit: even more relevant now after yesterday’s announcement that Animas is dropping out of the pump market in Australia

- I need to check and adjust my basal rates

- I need to do more reading about LCHF and decide if I want to take a more committed approach or continue with the somewhat half-arsed, but manageable and satisfactory way I’m doing it now – edit: sticking totally to the half-arsed way and happy about it!

- I need to remind myself that my tribe is always there and ask for help when I need it

- I need to make these!

And being a better PWD is knowing what I need from my HCPs and working out how to be clear about it, rather than expecting them to just know. (I forget that Legilimency is not actually something taught at medical school. #HarryPotterDigression)

So, if I was to sit down with my HCPs (or if they were to read my blog), this is what I would say:

- I need you to listen

- I need you to tell me what you need from me as well. Even though this is my diabetes and I am setting the agenda, I do understand that you have some outcomes that you would like to see as well. Talk to me about how they may be relevant to what I am needing and how we can work together to achieve what we both need

- I need you to be open to new ideas and suggestions. My care is driven by me because, quite simply, I know my diabetes best. I was the one who instigated pump therapy, CGM, changes to my diet and all the other things I do to help live with diabetes – edit: And now, I’m the one who instigated Loop and built my own hybrid closed-loop system that has completely revolutionised by diabetes management. In language that you understand, my A1c is the best it’s ever been. Without lows. Again: without lows! Please come on this journey with me…

- I need you to understand that you are but one piece of the puzzle that makes up my diabetes. It is certainly an important piece and the puzzle cannot be completed without you, but there are other pieces that are also important

- I need you to remember that diabetes is not who I am, even though it is the reason you and I have been brought together

- And to that – I need you to understand that I really wish we hadn’t been brought together because I hate living with diabetes – edit: actually, I don’t hate diabetes anymore. Don’t love it. Wish it would piss off, but as I write this, I’m kinda okay with it

- I need you to remember that I set the rules to this diabetes game. And also, that there are no rules to this diabetes game – edit: that may be the smartest thing I have ever written. I’d like it on a t-shirt

- I need you to understand that I feel very fortunate to have you involved in my care. I chose you because you are outstanding at what you, sparked an interest and are able to provide me what I need

- I need you to know that I really want to please you. I know that is not my job – and I know that you don’t expect it – but I genuinely don’t want to disappoint you and I am sorry when I do

- I want you to know that I respect and value your expertise and professionalism

- I need you to know that I hope you respect and value mine too.

And being a better PWD is being clear to my loved ones (who have the unfortunate and unpleasant experience of seeing me all the time – at my diabetes best and my diabetes worst) and helping them understand that:

- I need you to love me

- I need you to nod your heads when I say that diabetes sucks

- I need you to know I don’t need solutions when things are crap. But a back rub, an episode of Gilmore Girls or a trip to Brunetti will definitely make me feel better, even if they don’t actually fix the crapness

- Kid – I need you to stop borrowing my striped clothes. And make me a cup of tea every morning and keep an endless supply of your awesome chocolate brownies available in the kitchen

- Aaron – I like sparkly things and books. And somewhere, there is evidence proving that both these things have a positive impact on my diabetes. In lieu of such evidence, trust and indulge me!

- I need you to know I am sorry I have brought diabetes into our lives

- I need you to know how grateful I am to have you, even when I am grumpy and pissed because I am low, or grumpy and pissed because I am high, or grumpy and pissed because I am me.

- Edit: I need you to keep being the wonderful people you are. Please know that I know I am so lucky to have you supporting me.

This week, for the first time ever, I had no anxiety at all as I prepared for my visit to my endocrinologist. I always feel that I have to put in a disclaimer here, because I make it sound like my endo is a tyrant. She’s not. She is the kindest, loveliest, smartest, most respectful health professional I have ever seen. My anxieties are my own, not a result of the way she communicates with me.

Anyway, now that the disclaimer is done, I walked into her office with a sense of calm. And excitement. It was my first post-Loop appointment. I’d eagerly trotted off for an A1c the week earlier (another first – this diabetes task is usually undertaken with further feelings of dread) and was keenly awaiting the results.

But equally, I didn’t really care what the results were. I knew that I would have an in-range A1c – there was no doubt in my mind of that. I know how much time I am spending in range – and it’s a lot. And I have felt better that I have in a very, very long time.

The eagerness for the appointment was to discuss the new technology that has, quite honestly, revolutionised by diabetes management.

I sat down, she asked how I was. I marvelled – as I always do at the beginning of my appointments with her – how she immediately sets me at ease and sits back while I talk. She listens. I blabber. She never tries to hurry me along, or interrupts my train of thought. I have her full attention (although I do wonder what she must think as my mind goes off on weird, sometimes non-diabetes related tangents.)

And then I asked. ‘So…what’s my A1c? I had it checked last Wednesday.’ She told me and I took in a sharp breath. There it was, sitting firmly and happily in what I have come to consider ‘pregnancy range’. Even though that is no longer relevant to me, it frames the number and means something.

I shrugged a little and I think perhaps she was surprised at my lack of bursting into tears, jumping up and down and/or screaming. I wasn’t surprised. I repeated the number back to her – or maybe it was so I could hear it again. ‘And no hypos.’ I said. ‘And minimal effort.’

I’ve had A1cs in this range before. In fact, I managed to maintain them for months – even years – while trying to get pregnant, and then while pregnant. But the lows! I know that while trying to conceive and during pregnancy, I was hypo for up to 30% of the time. Every. Single. Day.

It was hard work. No CGM meant relying on frequent BGL checks – between 15 and 20 a day. Every. Single. Day. And it meant a bazillion adjustments on my pump, basal checking every fortnight and constantly second guessing myself and the technology. Sure, that A1c was tight, but it was the very definition of hard work!

This A1c was not the result of anywhere near as much effort.

Surely the goal – or at least one of them – of improved diabetes tech solutions has to be about easing the load and burden of the daily tasks of diabetes. I’m not sure that I’ve actually ever truly believed that any device that I have taken on has actually made things easier or lessened the burden. Certainly not when I started pumping – in fact, when I think about it, it added a significant load to my daily management. CGM is useful, but the requirement to calibrate and deal with alarms is time and effort consuming. Libre is perhaps the least onerous of all diabetes technologies, yet the lack of alarms means it’s not the right device for me at this time.

These tools have all been beneficial at different times for different purposes. It is undeniable they help with my diabetes management and help me to achieve the targets I set for myself. But do they make it easier to live with diabetes? Do they take about some of the burden and make me think less about it and do less for it? Probably not.

Loop does. It reduces my effort. It makes me think about my own diabetes less. It provides results that mean I don’t have to take action as often. It takes a lot of the thinking out of every day diabetes.

So let me recap: Loop has delivered the lowest A1c in a long time, I sleep better that I’ve slept in 20 years, I feel better – both physically and emotionally – than I have in forever. And I feel that diabetes is the least intrusive it has ever been.

Basically, being deliberately non-complaint has made me the best PWD I can possibly be.

Oh look! Your phone can now be deliberately non-compliant too, thanks to designer David Burren. Click on the link to buy your own. (Also comes in black and white.)

Following last week’s post about how my ADATS’ talk was received, several things happened. Firstly, I was contacted by a heap of people wanting to chat about the reaction. Secondly, I was sent several designs of logos and t-shirts with ‘deliberately non-compliant’ splashed across the front, which obviously I will now need to order and wear any time I do a talk (or am sitting opposite a diabetes healthcare professional). And thirdly, discussions started about how we manage our diabetes ‘off label’.

While off label generally refers to how drugs are used in ways other than as prescribed, it has also come to mean the way we tweak any aspect of treatment to try to find ways to make diabetes less tiresome, less burdensome, less annoying.

When it comes to making diabetes manageable and working out how to fit it into my life as easily and unobtrusively as possible, I am all about off label. And I learnt that very early on.

‘Change your pen tip after every use.’ I was told the day after I was diagnosed, meeting with a diabetes educator the first time. ‘Of course,’ I said earnestly, staring intently at the photos of magnified needles showing how blunt the needles become after repeated use. ‘Lancets are single use too.’ I nodded, promising to discard my lancets after each glucose check. ‘You must inject into your stomach, directly into the skin – never through clothes, and rotate injection sites every single time.’ I committed to memory the part of my stomach to use and visualised a circular chart to help remind me to move where I stabbed.

Fast forward about a week into diagnosis. Needle changed once a day (which then, in following weeks, became once every second day, every third day, once a week… or when ‘ouch – I really felt that’); I forgot that lancets could be changed; speared (reused) needles directly through jeans or tights into my thighs, having no idea which leg I’d used last time.

And then there were insulin doses. ‘You must take XX units of insulin with breakfast, XX with lunch and XX with dinner. That means you need XX grams of carbs with breakfast, XX with lunch and XX with dinner. These amounts are set and cannot be altered. You must eat snacks.’ I took notes and planned the weekly menu according to required carb contents. Within a week, I’d worked out that if I couldn’t eat the prescribed huge quantities of carbs, I could take less insulin and that all seemed to work out okay. And I worked out how I didn’t need to have the same doses each and every day. It was liberating!

I switched to an insulin pump and the instructions came again: ‘You must change your site every three days without fail.’ I promised to set alarms to remind me and write notes to myself. ‘Cartridges are single use,’ I was told and vowed to throw them away as soon as they were empty. Today, sometimes pump lines get changed every three days, sometimes three and a half, sometimes four and sometimes even five. Cartridges are reused at times…

I was also told to never change any of the settings in my pump unless I spoke with my HCP. But part of getting the most from a pump (and all diabetes technology) is about constantly reviewing, revising and making changes. I taught myself how to check and change basal rates – slowly and carefully but always with positive results. (For the record, my endo these days would not tell me to never change my pump settings.)

CGM came into my life with similar rules, and as I became familiar with the technology and how I interacted with it, I adapted the way I used it. Despite warnings of never, ever, ever bolusing from a CGM reading, I did. Of course I did. I restarted sensors, getting every last reading from them to save my bank balance. I sited sensors on my arms, despite warnings that the stomach was the only area approved for use. I started using the US Dex 5 App (after setting up a US iTunes account and downloading from the US App Store) because we still didn’t have it here in Australia, and I wanted to use my phone as a receiver, and seriously #WeAreNotWaiting.

And today…today I am Looping, which is possibly the extreme of using devices off label. But the reason for doing it is still the same: Trying to find the best ‘diabetes me’ for the least effort!

The push back to curating our diabetes treatment to fit in with our lives is often frowned upon by HCPs and I wonder why. Is it all about safety? Possibly, but I know that for me, I was able to always measure the risk of what I was doing off label and balance it with the benefit to and for me. I believe I have always remained as safe as possible while managing to make my diabetes a little more… well, manageable.

It can be viewed as rule breaking or ‘hacking’. It can be thought of as dangerous and something to be feared. But I think the concerns from HCPs go beyond that.

As is often the case, it comes down to control – not in the A1c sense of the word, but in the ‘who owns my diabetes’ way.

When we learn how things work, make changes and adapt our treatment to suit ourselves, we often find what works best is not the same as what we are told to do. And I think that some HCPs think that as we take that control – make our own decisions and changes to our treatment – we are making them redundant. But that’s not the case at all.

We need our HCPs because we need to be shown the rules in the first place. We have to know what the evidence shows, and we need to know how to do things the way the regulators want us to do them. We need to understand the basics, the guidelines, the fundamentals to what we are doing.

Because then we can experiment. Then we can push boundaries and see what is still safe. We can take risks within a framework that absolutely improves our care, but we still understand how to be safe. I understand the risks reusing lancets, or stretching out set changes by a day or two. Of course I do. I know them because I’ve had great HCPs who have explained it to me.

Going off label has only ever served to make me manage my diabetes better. It has made me less frustrated by the burden, less exasperated by the mundanity of it all.

And the thing that has made me feel better – physically and emotionally – about diabetes more than anything else is using Loop. So, use it I will!

It seems silly to have to say this, but I will anyway. Don’t take anything I write (today or ever) as advice. I’m not recommending that anyone do what I do and I never have.

I get to meet some pretty awesome people with diabetes around the globe. At EASD I caught up with Cathy Van de Moortele who has lived with diabetes for fifteen years. She lives in Belgium and, according to her Instagram feed, spends a lot of time baking and cooking. Her photos of her culinary creations look straight out of a cookbook…She really should write one!

I get to meet some pretty awesome people with diabetes around the globe. At EASD I caught up with Cathy Van de Moortele who has lived with diabetes for fifteen years. She lives in Belgium and, according to her Instagram feed, spends a lot of time baking and cooking. Her photos of her culinary creations look straight out of a cookbook…She really should write one!

Cathy and I were messaging last week and she told me about an awful experience she had when she was in hospital recently. While she wasn’t the target of the unpleasantness, she took it upon herself to stand up to the hospital staff, in the hope that other people would not need to go through the same thing. She has kindly written it out for me to share here. Thanks, Cathy!

______________

‘Good day sir. Unfortunately we were not able to save your toes. There’s no need to worry though. We’ll bring you back into surgery tomorrow and we’ll amputate your foot. It won’t bother you much. We’ll put some sort of prosthetic in your shoe and you’ll barely notice…’

I’m shocked. Still waking up from my own surgery, I’m in the recovery room. Between myself and my neighbour, there’s no more than a curtain on a rail separating us. I feel his pain and anxiety. He is just waking up from a surgery that couldn’t save his toes. This man, who is facing surgery again, leaving him without his foot. How is he gonna get through this day? How will he have to go on?

The nurse besides my bed, is prepping me to go back to my room. I tell him I’m shocked. He doesn’t understand. I ask him if he didn’t hear the conversation? His reaction makes me burst into tears.

‘Oh well, it’s probably one of those type 2 diabetics, who could not care less about taking care of himself.’

I’m angry, disappointed, sad and confounded. I ask him if he knows this person. Does he know his background? Did this man get the education he deserves and does he have a doctor who has the best interest in his patient? Is he being provided with the right medication? Did he have bad luck? Does he, as a nurse, have any idea how hard diabetes is?

The nurse can tell I’m angry. He takes me upstairs in silence. My eyes are wet with tears and I can only feel for this man and for anyone who is facing prejudice day in day out. I’m afraid to face him when we pass his bed. All I can see is the white sheet over his feet. Over his foot, without toes. Over his foot, that will no longer be there tomorrow. I want to wish him all the best, but no words can express how I feel.

What am I supposed to do about this? Not care? Where did respect go? How is this even possible? Why do we accept this as normal? Have we become immune for other people’s misery?

I file a complaint against the policy of this hospital. A meeting is scheduled. They don’t understand how I feel about the lack of respect for this patient. They tell me to shake if off. Am I even sure this patient overheard the conversation? Well, I heard it… it was disrespectful and totally unacceptable.

Medical staff need to get the opportunity to vent, I totally agree. They have a hard job and they face misery and pain on a daily basis. They take care of their patients and do whatever is in their power to assist when needed. They need a way to vent in order to go home and relax. I get that. This was not the right place. It was wrong and it still is wrong. This is NOT OKAY!