Whilst I am not supposed to consider my iPhone my primary care physician, today I am taking advice from it.

And adding coffee. Mainlining coffee. (File under #JetLagSucks.)

real life with diabetes

Whilst I am not supposed to consider my iPhone my primary care physician, today I am taking advice from it.

And adding coffee. Mainlining coffee. (File under #JetLagSucks.)

One of the highlight sessions I sat in on at ADA was Dr William Polonsky. Bill is the Co-Founder and President of the Behavioural Diabetes Institute, which you can read all about here. He also wrote the book Diabetes Burnout which is on the shelves of many, many people living with diabetes. I refer to it ALL THE TIME, and my copy has become incredibly dog-eared and annotated in recent times. And there was a period of about 6 months where I carried it around with me like a security blanket. (If you don’t have it, you can order it here.)

I’ve seen Bill speak at other conferences I’ve attended – he is one of the speakers I always make a point to hear because he absolutely ‘gets’ diabetes. His talks are always informative, amusing and offer great take-home messages for the mainly-healthcare professional audience. And he is gentle, kind and completely and utterly non-judgemental.

Yes – I am a complete and utter fan girl! But I did manage to keep myself together when I spoke with him a couple of times at the conference. And only slightly squealed when I heard he would be coming to Australia later this year. (Watch this space!)

His session at this year ADA had the title ‘Caring for the patient who doesn’t seem to care’ and right off the bat, Dr Polonsky highlighted the word ‘seem’ in the title.

He started by asking the audience how many of them had, in the past year, seen a patient who didn’t seem to care about their diabetes. Just about every hand in the room went up. Of course they did. Because for many – most? all? – of us living with diabetes, there are times when it all gets too much and we seem to not care.

But then he reminded everyone that even those who seem to not care about their diabetes want to live long, happy, healthy lives.

I don’t know anyone with diabetes – feeling good or not so good about their management – who isn’t hoping to be healthy. No one wakes up in the morning and says they want to have a crappy diabetes day. No one says ‘Diabetes is too much for me at the moment. I hope I have a really bad hypo.’ No one.

In times of burnout, where I absolutely know it looks like I couldn’t give a toss about my health, I wish so hard that I could find ways to break through the exhaustion and lack of motivation and find a way – any way – to do better at managing my diabetes.

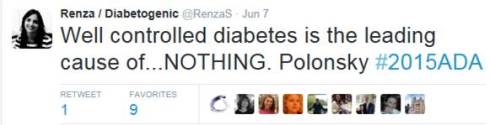

Other take home messages from Bill’s talk included the importance of talking about diabetes with a sense of urgency – however without threats. I loved how he suggested a reframing of the oft-quoted ‘diabetes is the leading cause of <insert complication>’, reminding us all of the following:

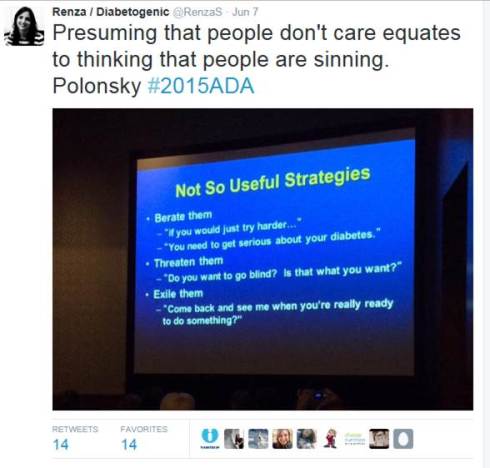

Dr Polonsky’s take home messages from this talk were many. He provided some strategies for what might work – and some that should be avoided.

I listen to talks like this and think they sound so logical and sensible, and wonder why it even needs to be said. But of course it does. Because sometimes – all too frequently – there is this idea that not managing diabetes as expected is a deliberate choice. Or that not getting the results that we all ‘should’ be getting is the fault of the person living with diabetes. Thank you to Dr Polonsky – and others like him, including Martha Furnell, Jill Weissberg-Benchell and our very own Professor Jane Speight – for understanding that there is no fault here. Just a need for better understanding and support.

Being a total fan girl here! Dr Polonsky is my hero.

I’m back from the American Diabetes Association Scientific Meeting and I am pleased to report that the world hasn’t ended. Despite having in the same room, at the same time (and multiple times!), healthcare professionals, people with diabetes, industry and health organisations, the earth continues to rotate around the sun and we’ve not been plunged into the darkness of the apocalypse. I am relieved.

Actually, I’m totally not. Not at all.

There is much that we can be critical of when it comes to the U.S. health system. But their inclusion of consumers (patients, whatever you want to call us) at conferences is, from where I am sitting, enviable.

I cannot count the number of patient advocates in attendance at this year’s ADA conference. But we were everywhere. We presented, we attended sessions, we connected with each other, we tweeted the hell out of the talks we attended, we spoke with the aforementioned HCPs and people from industry and health organisations. We made plans for ways we could all collaborate and initiated projects that would cross seas and continents and provide support for other people with diabetes.

And the conference was all the better for it.

I return home to where there is, unfortunately, limited collaboration. When there is some sort of partnership or alliance, it is often tokenistic. Frequently, these are the words I hear when a collaboration is first suggested ‘We’ve been told that we should speak with people with diabetes about this project/resource/activity/ program. We’ve been working on it for months/years/decades now, so we think it’s time we brought in someone with diabetes to tell us what they think’.

Let’s be clear: that’s not a partnership. That’s a ‘Shit, we forgot to talk to the people this is meant for. Quick. Do it now. Then we can say we’ve consulted.’

Well, no. Not really.

At our annual scientific meeting here in Australia, you will not see a consumer contingent. There may be a few rogue people there who manage to get by all the rules and regulations because we work in the diabetes field. But by and large, we are a rare sighting. This is, of course, partly due to the Therapeutic Goods Act which prohibits direct marketing of prescription medications to consumers. We are not free to wander around expo halls with the name of drugs in our faces. It is not considered appropriate that people with diabetes attend the sessions aimed at HCPs for fear that we would misconstrue or misunderstand or misrepresent what we are hearing.

But never in my time of attending an event where consumers are welcome have I seen that.

I attended the ADA Meeting to hear about the latest in diabetes. I wanted to go to sessions and hear from speakers about breakthroughs and research and studies that aim to improve the lives of those of us with diabetes. And I did. I spent a lot of time in those sessions. I spoke with the presenters afterwards and felt welcome and included. I asked the speakers when they would be in Australia and made them promise to do consumer talks when they get here – not just talks for HCPs.

And I also spent time speaking with people from industry and hearing about in-development products. I heard about the processes in the US and in other places for subsidies and asked about how they have gone about improving access to their technologies. And I begged that when they say that they have a global team working on something that they remember Australia – reminding them that we may be a long way away, but we are still part of their market.

And I did all this alongside other advocates. It’s amazing how loud our voice becomes when we are together.

DISCLAIMER TIME: Whilst in Boston at the ADA Scientific Meeting, I attended sessions funded by: Medtronic Diabetes: Johnson and Johnson Diabetes and Dexcom. I did not receive any financial (or other) remuneration for attending these sessions.

A couple of years ago, when CGM was first launched into Australia, the typical thing happened. The device company took their shiny new product to health professionals around the country, showing off their wares. There were dinners and events and showcases, all highlighting the new technology.

Now, obviously with a product like CGM which requires HCP initiation, it is important to promote the product to the people who will be getting consumers hooked up. I understand that.

Nonetheless, it was with much envy that I saw HCPs being given a trial of the product. They were connected to a CGM and given an empty pump for four days – the number of days a sensor was meant to be worn.

I was desperate to get my grubby hands on one of these. I had read all about CGM and how much people with diabetes living overseas loved it. I read about how it made people feel safer and less frightened about hypos. I learnt that it helped to level out …well…levels. It sounded exciting. I wanted to try it myself.

The HCPs on the trial I spoke to were incredibly dismissive about this technology. Over the few days they were wearing it, I heard comments such as ‘It’s making me obsessive’ or ‘I can’t stop looking at the pump and watching what’s going on’ or ‘When I calibrate it, the numbers don’t match exactly’ or ‘The infusion set insertion process is terrible. I bled everywhere!’

I heard them say repeatedly that the technology was rubbish, that it wasn’t worth the cost, and that all it would do for people with diabetes is make them more distressed and anxious about their diabetes. Plus, it hurt.

Not one of them had diabetes themselves.

I started to get annoyed. I recall sitting with one of them after hearing this pronouncement yet again, feeling quite angry. ‘You know,’ I said. ‘You don’t get to say these things. You don’t get to write off this technology after a few days of wearing it, making claims that it is pointless. This is the latest technology that we have to manage our diabetes. It’s first generation so of course it’s not perfect. The second, third and probably even fourth gen products probably won’t be perfect either. But it is a new and worthwhile tool to help us manage our condition. It is exciting. We are hopeful. You don’t get to trash it.’

I remembered this whilst siting in a session on the first day here at the American Diabetes Association Scientific Meeting. It was a ‘Meet the Expert’ session and the topic was about personal experiences of the artificial pancreas.

Kelly Close (she’s amazing – read all about her here) was talking about her experiences of being involved in trials for a couple of different artificial pancreas projects. It was fascinating hearing about the AP and her excitement about the current technology being trialled – and about what is still coming.

Her enthusiasm was obvious. In fact she actually commented on why enthusiasm and excitement need to be employed when talking about advances in technology. We need to create a buzz and have people talking and asking questions and going on trials and writing (and blogging) about our experiences.

On the panel with Kelly was Chris Aldred (better known as The Grumpy Pumper) whose role in the session was to be the one challenging all the hype. He immediately explained that he had not used the AP, and had some questions. He was skeptical about a few things.

Being skeptical is absolutely okay. We shouldn’t ever blindly accept any new treatment without asking questions, but that actually adds to the buzz. It forces people who have experience with the device to talk about the good things and its limitations. It also helps alleviate a lot of the concerns people may have.

I thought back to my experience with the launch of CGM back home. When the HCPs who were privileged to try the then-new tech were trashing the product, I wish that there had been a voice to be able to respond to those concerns. I wish that the trial of the product had been extended to people with diabetes who could see it for what it was and how its application worked in the real world. And who could share their experiences – absolutely the good and the bad – with other PWD.

That’s exactly what I did when I finally got to try CGM. You bet the first gen was clunky. It did have accuracy problems and I did bleed a little most times the sensor was inserted. But whoa! It was amazing technology for the time and made a huge difference to me. When I understood how the trends worked, I knew how to respond to them. I could address things before they became problems.

I left the AP session on the first day pretty excited and inspired. And wanting to be part of the buzz – either as a trial participant or as someone on the periphery talking about it, reading about it, hearing people speak about it.

Read more at diaTribe where Kelly shares her AP trial experiences.

‘Are you here for work?‘ It was just after 7am in LA, and the border security officer looked tired. He studied my passport, holding it up, comparing the photo with the even-more tired-looking, and rather dishevelled, person standing in front of him.

‘Yes. For a conference in Boston.‘ I said, trying to smooth my hair.

‘Oh, the diabetes one?’

‘Yes. That’s right.’ I said. My flight from Melbourne was full of people attending the ADA conference. I know this because I knew half of them. Plus I kept hearing snippets of conversation with ‘diabetes’ being thrown around.

‘My mum (mom!) has diabetes. Type 1. She should go.‘ He said. He flipped through my passport. ‘How long are you here for?’

‘Only for the conference and then three days in New York. I’ll be home in nine days.’

‘That’s not long after travelling so far,’ he said to me.

I smiled. ‘You’re so right. But I’ve left my family home this time. So I don’t really mind only being away for a short time.’

‘Enjoy the conference.’ He stamped my passport and was about to hand it back to me when he looked at me again. ‘Do you have diabetes?’

‘Yes. I do,’ I said. ‘I have type 1. Like your mum.’

‘Do you use a pump?‘ he asked.

‘Yes. And I’m wearing a CGM as well.’

‘My mom needs to talk to you,’ he said. ‘You look healthy. Keep it up.’ He passed me my papers.

‘Thanks. I hope your mum is okay,’ I said, noticing the concerned look on his face – one frequently worn by loved ones of people with diabetes. He nodded and I walked off, heading towards the baggage carousel.

A typical, frantic, ‘I’m so disorganised’ few hours before getting to the airport. But I have insulin. And I have a CGM fastened to my stomach and an insulin pump tucked in my bra. There are pump supplies in my carry on. Anything else I’ve forgotten can be found easily at the other end.

Don’t forget to follow #2015ADA!

Tomorrow, I am flying to Boston to attend the American Diabetes Association 75th Scientific Sessions. (Play along from home by following #2015ADA!)

There will be a strong consumer (reminder to self – use ‘patient’) contingent, which is always terrific. I get to catch up with old friends from the DOC and hear what they have been up to. I learn about new consumer patient-led advocacy efforts that manage to cut through in a way that only people living with diabetes can. I am reminded that conferences ARE the place for people living with the health condition that is being spoken about at that conference.

I attend conferences with my eyes wide open and leave with great excitement. I see new technologies yet to be released here, or still in development. I hear from people on trials of new drugs and devices. And I see the potential and possibilities for making diabetes easier, more streamlined, more user-focused and feel inspired and hopeful. This is good.

But, I am approaching this conference with a slightly different attitude. With some of the recently announced changes to diabetes supplies in Australia (as I wrote about here and here), I really want to speak with some of my US DOC friends about what it means to be reliant on a health system that limits choice. We have never really had that to date.

Whilst we may not have access to every pump or meter on the market, the consumables for the devices that are here have been available to all. Distribution has been overseen by Diabetes Australia (please read the disclaimer in this post!!) – an organisation representing people with diabetes, not big business or shareholders.

Last night, I attended a dinner at Parliament House in Canberra for the Parliamentary Friends of Diabetes Group. It was a grand occasion, attended by many influential politicians. Health Minister, Sussan Ley made this comment:

This is, indeed a noble pursuit.

Diabetes Australia President, Judi Moylan stated:

I would ask that in amidst all of those politically-charged reviews, reports and cost-cutting measures that seem to be the focus of diabetes in Australia at the moment, the human aspect is identified. It is hard to find amongst all the facts and figures.

But it is absolutely critical for our leaders to consider if they want to do best by people living with diabetes. Extraordinary leaders would search for it, find it – and make sure they listen to it. And remember that those extraordinary leaders include people living with diabetes.

Living with a chronic health condition frequently means lots of health checks. This could mean regular blood tests, X-rays, scans or other things performed by HCPs. Or, as in the case with diabetes, it means ongoing, regular, daily (and several times daily) BGL checks.

Hopefully health checks are all meaningful. By that, I mean they are done for a specific reason and with particular action taken depending on the result.

I thought about this the other day. I was speaking with someone who had argued with her GP after she had made an appointment for a routine check – a Pap smear. Now, this woman (who is happy for me to share this story) is very connected with her healthcare. She sees her diabetes team regularly and is always up to date with her complications screening. She gets pats on the back from the compliance police.

Her GP knows this because she makes sure that her diabetes team update her GP.

The GP’s role in diabetes is different for everyone. I have a great GP, but he knowns that when it comes to diabetes, his role begins and ends with ‘You still have diabetes, right?’ And then we laugh and tick ‘diabetes’ off the list. Others have their GP as their primary care physician.

My friend has the same sort of relationship with her GP as do I. She is also as vocal as I am when it comes to being very clear about the direction of medical appointments. So when she walked into her appointment, she made it very clear that she was there for a Pap test and that was it.

After she had her Pap test, her GP asked her to step on the scales. ‘Oh,’ said my friend. ‘Why?’

It’s exactly the question I would ask. ‘Why?’ And it is the most useful question when it comes to healthcare. I ask it all the time which is really important when your healthcare professional is more from the school of ‘you will do this‘ rather than ‘this is an idea for us to discuss.’

I am more than happy to be thought of as a petulant toddler in the eyes of my healthcare professionals. I expect things to be explained to me – how else am I meant to make an informed decision about my healthcare?

Too frequently, we are asked to submit to tests (as basic as weight, or something far more complicated) or change our medication or treatment without an explanation as to why this is a good thing.

And frequently we do it without thinking.

Part of being in control of my healthcare is to have full understanding about why we are doing what we do. I check my BGL to give me information to use when it comes to deciding what I will eat or how much insulin I need; I have my blood pressure checked to see if it has changed from the last time I had it checked and if so, if anything needs to be done. I also know it can be a predictor of other things related to diabetes, so it’s something that needs to be checked regularly.

But I refuse to have a check done unless there is a good reason and ‘Oh, just because’ is not a good reason. And that is the reason that my friend’s GP gave her. ‘Do you have some concerns about my weight?’ asked my friend. ‘Do I look different to last time I saw you? I don’t have any concerns, so I’m confused as to why you would suggest it?’

Now, you can absolutely say that my friend was making a big deal over nothing, I disagree. If there is no reason, why have it done? I could go into something about weight being a fraught issue for a lot of people ( I won’t step onto the scales unless I absolutely have to), but actually that doesn’t matter.

There needs to be a reason. If there is no satisfactory and satisfying response to ‘why?’ it doesn’t happen. Simple as that!

There is much inequality with the health system here in Australia. I know that we have it better than a lot of other countries, but unfortunately, it’s not fair for all. However, there are some things that are, indeed, great.

I have always been exceptionally proud of our National Diabetes Services Scheme. I love telling people about it when I am travelling, explaining how it makes the lives of people with diabetes considerably easier. We don’t need to get our health insurance providers involved; no one is forcing us to use one particular make of meter or strips because that is all that is covered; registering on the NDSS is not all that difficult.

The NDSS has been around since 1987, and in a health system of oft-quoted disparity, it is a shining light in its fairness. (I say this with full knowledge and understanding that people with type 2 diabetes do not have access to insulin pump consumables, but this therapy is primarily used by people with type 1 diabetes – even before the NDSS subsidy came into effect back in 2004.)

However, when it has come to needles, BGL strips and other consumables required in the management of diabetes there has been no discrimination; it has been available to all.

Until now.

Last week, Commonwealth Health Minister, Sussan Ley, announced that following the findings of the Post-Market Reviews of Products Used in the Management of Diabetes, BGL strips would no longer be available to people with non-insulin-treated type 2 diabetes as they have been to date, questioning the effectiveness of self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG) for this group.

The report (Part 1 – Blood Glucose Test Strips) announced that people with non-insulin-treated type 2 diabetes will have limited access to BGL strips. That is, access will be provided for up to 12 months’ supply of strips – initially six months and then an additional six months if it is determined the person with diabetes will benefit from further monitoring. The decision is in the hands of the healthcare professional – not the person with diabetes.

The Minister claims these findings to be in line with the Choose Wisely campaign, which, when it comes to type 2 diabetes, I also consider to be flawed.

When the PBAC reviews were first announced (back at the end of 2012), I wrote this piece for the Diabetes Victoria blog about why limiting access to diabetes consumables for any group of people with diabetes is potentially damaging – especially when it relates to taking ownership of managing diabetes – and short sighted. I actually think it is downright irresponsible policy making.

The findings of this review concern me – they worry me greatly. This is the first step in removing control of the tools we need to manage our diabetes in the way we choose. The removal of choice is destructive and limits our ability to tailor our healthcare to our needs.

I don’t have type 2 diabetes, so this in no way affects what I am able to access through the NDSS. But I know many people with non-insulin-treated type 2 diabetes who rely on regular BGL monitoring to assist them to live well with diabetes. They use it as a tool to make better food choices, noting how certain foods affect their BGLs. They use it to monitor the effectiveness of exercise as part of their diabetes management. And they use it because it gives them a sense of control, piece of mind and ownership over their health.

This is sending the message that non-insulin-treated type 2 diabetes is not serious. And that is a very, very dangerous statement to be making.

Disclaimer – I was involved in Diabetes Australia’s submission to the PBAC on all aspects of the Post-Market Reviews of Products Used in the Management of Diabetes. Diabetes Australia strongly supported SMBG for people with non-insulin-treated type 2 diabetes in Part 1 of the reviews.

I had a lovely dinner last night with a colleague and friend. We ate great food, drank terrific cocktails and didn’t shut up except for when the waiter was telling us the evening’s specials (and even then we ‘oohed’, ’aahed’ and ‘yummed’ our way through that).

At one point, my friend reminded me of a beautiful part of the book Captain Corelli’s Mandolin, a book I read when it first came out back in the mid-1990s.

As soon as I got home from our dinner, I searched for it so I could read the words again. Here they are:

When I first read the book, these words kind of washed over me. I was hearing them quoted a lot, and in the coming years I heard them read at weddings. They are beautiful words; read aloud it is beautiful prose.

But it wasn’t until last night that I read it and felt really understood it. The poem is an ode to enduring love, but that’s not what struck me. At least, not necessarily the love bit. But the endurance bit certainly did.

Over the last couple of years, things have been difficult. When I look at how I have been managing my diabetes, it has been a series of fits and starts. There are spurts of focus, then dips of almost denial. There are times of desperation and exhaustion and then periods of energy. It’s uneven. New devices see me get enthusiastic and motivated, but only for a short period. Then I return to the slump.

It’s not the exhilarating times that matter. Of course they are wonderful and enjoyable and sustaining and thrilling. Having a new pump or a new meter or a new CGM is a sure-fire way to get me thinking more about diabetes. But this doesn’t last. And it also doesn’t really count.

Equally, it’s not the slumps that matter.

What really matters is actually what you might call the boring times. It’s what comes before and after the flurry of interest of a new toy. Or the times around the ‘nosedives’. I feel best about my diabetes management not when I am stressed about how little I am doing or happy because I am so focused. It is actually the time when it is just there, plodding along, being considered at an ‘appropriate’ level. It’s not sexy. It’s not dramatic. But it’s so good because I feel relaxed and comfortable about it. It just is.

I am sure that there is something to be said about the fast-paced world we live in and this idea that we always need to be thrilled by something new. It’s too easy to get complacent and comfortable. That’s probably one of the reasons that I embrace new and emerging technologies with such zealousness.

However, if I was relying only on the new stuff to sustain me, it would never last. A new pump becomes just a pump very quickly. A new meter stops being new and shiny after a while and becomes just a meter. And a CGM may be magical and brilliant and life-changing until it become just another tool in the diabetes tool kit. That doesn’t make them any less important or valuable. But if I was relying on the excitement of the new, I would need a new toy every week or so!

The endurance of ‘just being’. That’s the sweet spot. That’s when I know I am getting it right. I just wish I could work out how to be there a whole lot more!

I am lucky that Aaron is always listening to new music. This CD was a recent purchase. Sometimes I hear something that makes me just so delighted. Like this live performance of my favourite track from the CD.