I would do almost anything to avoid a visit to the emergency department. The times it’s been unavoidable have never been fun. They’ve been chaotic, scary and generally involved some sort of battle about my diabetes. Sometimes it’s been a demand to remove my pump, or refusal to accept CGM data. One time, I was told that I needed to hand over my insulin (and pump) and that I was not allowed to ‘do anything diabetes’. The level of self-advocacy needed to simply be permitted to do the things I do every single minute of every single day was exhausting – on top of the reason why I was there in the first place.

Emergency departments are overburdened machines, and when sharing my experiences, I’m not being critical. There are so many moving parts and the health professionals staffing them are not experts in diabetes. My frustration isn’t really about that lack of specialty; it’s that they refuse to recognise mine.

So, imagine what it would be like to be able to have emergency department care with specialised diabetes care. And to make it even better, imagine you could get that care from home.

Say hello to the Victoria Virtual Emergency Department – Diabetes Service (and a new acronym to add to the diabetes vernacular: VVED-Diabetes). This is not a unicorn, utopia or Camelot. It’s a real service that exists right now for Victorians with diabetes needing urgent care! It was launched last week during National Diabetes Week at an event that showcased not only this new brilliant service, but also the way that people with diabetes were integral to the design of the service.

The VVED isn’t new. It’s been around for some time now. I first became aware of the service at the end of 2022 when I got COVID and was directed to the service from the Victorian Government’s COVID page. This Twitter thread gives an overview of my experience which was nothing short of stellar. I raved about the VVED to anyone who would listen, including family and friends, random people at Woolies and my poor pharmacist who started to look wary any time I walked into his store, lest I lecture him again about how he should be telling EVERYONE about it.

The diabetes addition to the VVED is new, however. It’s has come together after a massive effort from some truly remarkable people. The process has been so smart because it’s been done in the most collaborative way with a number of different groups to make sure that every single emergency care base is covered. Northern Health, the Victorian Government, Ambulance Victoria, ACADI, Diabetes Victoria and the Victorian and Tasmanian PHN Alliance were all involved in setting up the service, and community members (independently, and also through their involvement in those organisations) provided the lived experience input.

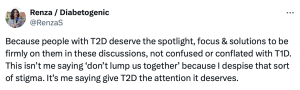

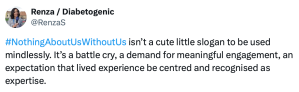

And that lived experience contribution was critical. We had some brilliant conversations when the guidelines for the service were being developed about the theory versus the practicalities of a PWD needing and emergency consult. I love that these guidelines differ from the generic guidelines in a regular emergency department because they are all about diabetes, and even more so, the person living with it!

The idea is that using a smart device with a camera you contact the VVED (more details on the flyer below) if you have an issue that needs urgent care. You will speak directly with healthcare professionals who will be able to assess your situation and decide a plan of action. In many situations, they will be able to assist you virtually, saving a trip to and lengthy wait in the emergency department.

Of course, in the situation of life-threatening conditions, call an ambulance urgently.

This is the sort of service that goes a long way to making diabetes a little easier. How fabulous to be able to manage difficult diabetes situations at home, with the knowledge that you’re receiving expert advice and care. VVED-Diabetes is a service that provides the necessary expertise while also recognising the abilities and experiences of those of us living with diabetes, paving the way for a far better urgent care experience. When we talk about person-centred care, this is a great example. More please!

This flyer explains all about the service and click here to go to the VVED website.