You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Language’ category.

Last week I was in Geneva for the 78th World Health Assembly (WHA78). It’s always interesting being at a health event that is not diabetes specific. It means that I get to learn from others working in the broader health space and see how common themes play out in different health conditions.

It’s also useful to see where there are synergies and opportunities to learn from the experiences of other health communities, and my particular focus is always on issues such as language and communications, lived experience and community-led advocacy.

What I was reminded of last week is that is that stigma is not siloed. It permeates across health conditions and is often fuelled by the same problematic assumptions and biases that I am very familiar with in the diabetes landscape.

I eagerly attended a breakfast session titled ‘Better adherence, better control, better health’ presented by the World Heart Federation and sponsored by Servier. I say eagerly, because I was keen to understand just how and why the term ‘adherence’ continues to be the dominant framing when talking about treatment uptake (and medication taking). And I wanted to understand just how this language was acceptable that this was being used so determinately in one health space when it is so unaccepted in others. This was a follow on from the event at the IDF Congress last month and built on the World Heart Foundation’s World Adherence Day.

While the diabetes #LanguageMatters movement is well established, it is by no means the only one pushing back on unhelpful terminology. There has been research into communication and language for a number of health conditions and published guidance statements for other conditions such as HIV, obesity, mental health, and reproductive health, all challenging language that places blame on individuals instead of acknowledging broader systemic barriers.

I want to say from the outset that I believe that the speakers on the panel genuinely care about improving outcomes for people. But words matter as does the meaning behind those words. And when those words are delivered through paternalistic language it sends very contradictory messages. The focus of the event was very much heart conditions, although there was a representative from the IDF on the panel (more about that later). But regardless the health condition, the messaging was stigmatising.

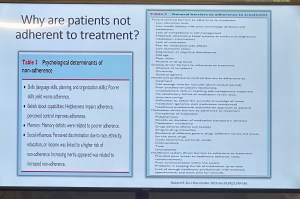

The barriers to people following treatment plans and taking medications as prescribed were clearly outlined by the speakers – and they are not insignificant. In fact, each speaker took time to highlight these barriers and emphasise how substantial they are. I’m wary to share any of the slides because honestly, the language is so problematic, but I am going to share this one because it shows that the speakers were very aware and transparent about the myriad reasons that someone may not be able to start, continue with or consistently follow a treatment plan.

You’ll see that all the usual suspects are there: unaffordable pricing, patchy supply chains, unpleasant side effects, lack of culturally relevant options, varying levels of health literacy and limited engagement from healthcare professionals because working under conditions don’t allow the time they need.

And yet, despite the acknowledgement there is still an air of finger pointing and blaming that accompanies the messaging. This makes absolutely no sense to me. How is it possible to consider personal responsibility as a key reason for lack of engagement with treatment when the reasons are often way beyond the control of the individual?

The question should not be: Why are people not taking their medications? Especially as in so many situations medications are too expensive, not available, too complicated to manage, require unreasonable or inflexible time to take the meds, or come with side effects that significant impact quality of life. Being told to ‘push through’ those side effects without support or alternatives isn’t a solution. It is dismissive and is not in any way person-centred care.

The questions that should be asked are: How do we make meds more affordable, easier to take, and accessible? What are the opportunities to co-design treatment and medication plans with the people who are going to be following them? How do we remove the systemic barriers that make following these plans out of reach?

One of the slides presented showed the percentage people with different chronic conditions not following treatment. Have a look:

My initial thought was not ‘Look at those naughty people not doing what they’re told’. It was this: if 90% of people with a specific condition are not following the prescribed treatment plan, I would suggest – in fact, I did suggest when I took the microphone – the problem is not with the people.

It is with the treatment. Of course it is with the treatment.

The problem with the language of adherence is that it frames outcomes through the lens of personal responsibility. It absolves policy makers of any duty to act and address the structural, economic and systemic barriers that prevent people from accessing and maintaining treatment. Why would they intervene and develop policy if the issue is seen as people being lazy or not committing to their health?

And it means the healthcare professionals are let off the hook. It assumes they are the holders of all knowledge, the giver of treatment and medications, and the person in front of them is there do what they are told.

There is no room in that model for questions, preferences, or complexity. There is no room for lived experience. There are no opportunities for co-design, meaningful engagement or developing plans that are likely to result in better outcomes.

When the room was opened up to questions, I raised these concerns, and the response from the emcee was somewhat dismissive. In fact, she tried to shut me down before I had a chance to make my (short) comment and ask a question. I’ve been in this game long enough to know when to push through, so I did. I also don’t take kindly to anyone shutting down someone with lived experience, especially in a session where our perspective was seriously lacking. Her response was to suggest that diabetes is different. I suggest (actually, I know) she is wrong.

And I will also add: while there was a person with lived experience on the panel, they were given two questions and had minimal space to contribute beyond that. I understand that there were delays that meant they arrived just in time for their session, but they were not included in the list of speakers on the flyer for the event while all the health professionals and those with organisation affiliation were. There comments were at the very end of the session, and I was reminded of this piece I wrote back in 2016 where health blogger and activist Britt Johnson was expected to feel grateful that the emcee, who had ignored her throughout a panel discussion, gave her the last five minutes to contribute.

Collectively this all points to a bigger issue, and we should name that for what it is: tokenism.

I didn’t point this out at the time, but here is a free tip for all health event organisers: getting someone to emcee who is a journalist or on-air reporter does not necessarily a good emcee make. Because when you have someone with a superficial understanding of the nuance and complexity involved in living with a chronic health condition, or understand the power dynamics and sensitivities required when facilitating a conversation about long-term health conditions, you wind up with a presenter who may be able to introduce speakers, but you miss out on meaningful and empathetic framing of the situation. There are people with lived experience who are excellent emcees and moderators, and bring that authenticity to the role. Use them. (Or get someone like Femi Oke who moderated the Helmsley + Access to Medicine Foundation session later in the day. She had obviously done her homework and was absolutely brilliant.)

I know that there has been a lot of attention to language in the diabetes space. But we are not alone. In fact, so much of my understanding has come from the work done by those in the HIV/AIDS community who led the way for language reform. There are also language movements in cancer care, obesity, mental health and more. And even if there are not official guidelines, it takes nothing to listen to community voices to understand how words and communication impact us.

So where to from here? In my comment to the panel, I urged the World Heart Foundation to reconsider the name of their campaign. Rather than framing their activities around adherence, I encouraged them to look for ways to support engagement and work with communities to find a balance in their communications. I asked that they continue to focus on naming the barriers that were outlined in the presentations, and shift from ‘How to we get people to follow?’ to ‘How do we work with people to understand what it is that they can and want to follow?’.

Finally, it was great to see International Diabetes Federation VP Jackie Malouf on the program on the panel. She was there to represent the IDF, but also brought loved experience as the mother of a child with diabetes. The IDF had endorsed World Adherence Day and perhaps had seen some of the public backlash about the campaign and the IDF’s support. Jackie eloquently made the point about how the use of the word was problematic and reinforced stigma and exclusion, and that there needs to be better engagement with the community before continuing with the initiative.

One of the things of which I am most proud is seeing how the language matters movement has really made people stop and think about how we communicate about diabetes. Of course, there’s still a long way to go, but it is very clear that there have been great strides made to improve the framing of diabetes.

One area where there has been a noticeable difference is at diabetes conferences. I’m not for a moment suggesting that there is never negative language used at conferences and meetings, but the clangers stand out now and are likely to be highlighted by someone (i.e. #dedoc° voices) in the audience.

Earlier this month, the 75th IDF World Congress was held in Bangkok. Sadly, there was no livestream of the Congress, but it’s a funny thing when you have a lot of friends and colleagues (i.e. #dedoc° voices) in attendance. It meant that I had my own livestream. Sadly, the majority of what I was being sent were the language clangers.

But let’s step back a week or so to before the Congress even started. I was feeling horrendous and my brain was in a foggy, virus haze, yet I still managed to be indignant and vent at the horrendously titled ‘World Adherence Day’ which was being ‘celebrated’ on 27 March. Here is my post from LinkedIn, which has been viewed close to 12,000 times:

What I didn’t say in my post was that the IDF had eagerly endorsed the day with a media release and social media posts. My LinkedIn post took all my energy for that day, and I didn’t get a chance to follow up with the IDF. Plus, I assumed their attention would have been focused very much on the upcoming Congress.

Also, I hoped that it was a one-off misstep. I mean, surely the organisation had learnt its lesson after the Congress in South Korea when I boldly challenged incoming-president Andrew Boulton for his suggestion that people with diabetes need some ‘fear arousal’ to understand how serious diabetes is. You can see the video of my response to that at the end of this post and read the article I co-authored (Boulton was another co-author) about language here.

Alas, I was wrong. Just days before the Congress started, I saw flyers for this session shared online:

I was horrified and commented on a couple of the posts I saw. I was surprised to see some responses from advocates which amounted to ‘We can deal with it when we get there.’ Here are reasons that isn’t good enough. Firstly – not everyone is there, so all they see is the promotional of an event, comfortably using stigmatising language. It suggests that this language and the meaning behind it is okay. The discussion shouldn’t be happening after the fact. In fact, the question we should be asking is: HOW did this even happen? Where were the people with lived experience on the organising committee of the Congress speaking up about this? Did they get to see it before it was publicised? And how did the IDF miss it? This is, after all, the organisation that launched a ‘Language Philosophy’ document in 2014 (which sadly seems to be unavailable online today). It’s also the organisation that has invited me to give a number of talks about the importance of using appropriate and effective communication to IDF staff, attendees of the Young Leaders Program and as an invited speaker at a number of Congresses.

A major sponsor at the IDF Congress seemed to be very excited about the word adherence. In fact, it appeared over and over in their materials at the Congress. Here is just a couple of their questionable messaging sent to me by people (i.e. #dedoc° voices) attending the Congress:

I will point out that the IDF obviously understands the impact of stigma on people with diabetes and the harm it causes. There were sessions at the Congress dedicated to diabetes-related stigma and how to address it. In fact, I had been invited to give one of those talks. But what is disappointing is that despite this, terminology that contributes to stigma is being used without question.

I wasn’t at the Congress but from what I saw there was indeed a vibrant lived experience cohort there. #dedoc° had a scholarship program, and, as usual, there was a Living with Diabetes stream. However, I will point out that the LWD stream was not chaired by a grassroots advocate as has been the case for all previous LWD streams. It was chaired by a doctor with diabetes and while I am in no way trying to delegitimise his lived experience, I am unapologetically saying that this is a backwards step by the IDF. When there is an opportunity for a person with diabetes who is not also a health professional is given to a health professional or a researcher, that’s a missed opportunity for a person with diabetes. There were seven streams at the IDF Congress. All except for one are 100% chaired by clinicians and researchers. Only the LWD stream is open to PWD. I know that when I chaired the stream, the four members of the committee were diligent about looking through the entire and identifying any sessions that could be considered problematic for people with diabetes. It appears that didn’t happen this time.

All of this points to a persistent disconnect. It is undeniable that the language matters movement is growing, but it is still not embedded across the board—even within organisations that should know better. If we are serious about addressing stigma and centring lived experience in diabetes care, then language can’t be an afterthought or a debate to have after the posters are printed and the sessions are underway. It must be part of the planning and the review process. The easiest way to connect the dots is to ensure the lived experience community is not only present, but also listened to, respected, and in positions to influence and lead. We are long past the point where being in the room or offered a solitary seat is enough – the room is ours; we are the table.

Postscript:

I have written extensively on why language – and in particular the word ‘adherence’ – is problematic. It’s old news to me and to many others as well. This piece isn’t about that. But if you want to know why it’s problematic, here’s an old post you can read.

Disclosures:

I was an invited to give a talk about diabetes-related stigma at the IDF Congress in Bangkok, but disappointingly, had to cancel my attendance due to illness. The invitation included flights and accommodation as well as Congress registration. I was also on the program for two other sessions and was due to present to the YLD Program.

Other IDF disclosures: I have been faculty for the YLD Program for the last 10 years; I chaired the LWD Stream at the 2019 Congress and was deputy chair of the 2017 Congress.

So often, there is amazing work being done in the diabetes world that is driven by or involves people with lived experience. Often, this is done in a volunteer capacity – although when we are working with organisations, I hope (and expect) that community members are remunerated for their time and expertise. Of course, there are a lot of organisations also doing some great work – especially those that link closely with people with diabetes through deliberate and meaningful community engagement.

Here are just a few things that involve community members that you can get involved in!

AID access – the time is now!

It’s National Diabetes Week in Australia and if you’ve been following along, you’ll have seen that technology access is very much on the agenda. I’m thrilled that the work I’ve been involved in around AID access (in particular fixing access to insulin pumps in Australia) has gained momentum and put the issue very firmly on the national advocacy agenda, which was one of the aims of the group when we first started working together. Now, we have a Consensus Statement endorsed by community members and all major Australian diabetes organisations, a key recommendation in the recently released Parliamentary Diabetes Inquiry and widening awareness of the issue. But we’re not done – there’s still more to do. Last week I wrote about how now we need the community to continue their involvement and make some noise about the issue. This update provides details of what to do next.

And to quickly show your support, sign the petition here.

Language Matters pregnancy

Earlier this week we saw the launch of a new online survey about the experiences of people with diabetes before, during and after pregnancy, specifically the language and communication used around and to them. Language ALWAYS matters and it doesn’t take much effort to learn from people with diabetes just how much it matters during the especially vulnerable time when pregnancy is on the discussion agenda. And so, this work has been very much powered by community, bringing together lots of people to establish just how people with diabetes can be better supported during this time.

Congratulations to Niki Breslin-Brooker for driving this initiative, and to the team of mainly community members along with HCPs. This has all been done by volunteers, out of hours, in between caring for family, managing work and dealing with diabetes. It’s an honour to work with you all, and a delight to share details of what we’ve been up to!

Have a look at some of the artwork that has been developed to accompany the work. What we know is that it isn’t difficult to make a change that makes a big difference. The phrases you’ll see in the artworks that are being rolled out will be familiar to many people with diabetes. I know I certainly heard most of them back when I was planning for pregnancy – two decades ago. As it turns out, people are still hearing them today. We can, and need to change that!

You can be a part of this important work by filling in this survey which asks for your experiences. It’s for people with diabetes and partners, family members and support people. They survey will be open until the end of September and will inform the next stage of this work – a position statement about language and communication to support people with diabetes.

How do I get involved in research?

One of the things I am frequently asked by PWD is how to learn about and get involved in research studies. Some ideas for Aussies with diabetes: JDRF Australia remains a driving force in type 1 diabetes research across the country, and a quick glance at their website provides a great overview. All trials are neatly located on one page to make it easy to see what’s on the go at the moment and to see if there is anything you can enrol in.

Another great central place to learn about current studies is the Diabetes Technology Research Group website.

ATIC is the Australasian Type 1 Diabetes Immunotherapy Collaboration and is a clinical trials network of adult and paediatric endocrinologists, immunologists, clinical trialists, and members of the T1Dcommunity across Australia and New Zealand, working together to accelerate the development and delivery of immunotherapy treatments for people with type 1 diabetes. More details of current research studies at the centre here.

HypoPAST

HypoPAST stands for Hypoglycaemia Prevention, Awareness of Symptoms and Treatment, and is an innovative online program designed to assist adults with type 1 diabetes in managing their fear of hypoglycaemia. The program focuses on hypoglycaemia prevention, awareness of symptoms, and treatment, offering a comprehensive range of resources, including information, activities, and videos. Study participants access HypoPAST on their computers, tablets, or smartphones.

This study is essential as it harnesses technology to provide practical tools for better diabetes management, addressing a critical need in the diabetes community. By reducing the anxiety associated with hypoglycaemia and improving symptom awareness and treatment strategies, HypoPAST has the potential to enhance the quality of life for individuals with type 1 diabetes.

The study is being conducted by the ACBRD and is currently recruiting participants. It’s almost been fully recruited for, but there are still places. More information here about how to get involved.

Type 1 Screen

Screening for T1D has been very much a focus of scientific conferences this year. At the recent American Diabetes Association Scientific Sessions, screening and information about the stages of T1D were covered in a number of sessions and symposia. Here in Australia. For more details about what’s being done in Australia in this space, check out Type 1 Screen.

And something to read

This article was published in The Lancet earlier in the year, but just sharing here for the first time. The article is about the importance of genuine consumer and community involvement in diabetes care, emphasising the benefits and challenges of ensuring diverse and representative participation to meet the community’s needs effectively.

I spend a lot of time thinking a lot about genuine community involvement in diabetes care and how people with diabetes can contribute to that ‘from the inside’. And by ‘inside’ I mean diabetes organisations, industry, healthcare settings and in research. I may be biased, but I think we add something. I’m grateful that others think that too. But not always. Sometimes, our impact is dismissed or minimised, as are the challenges we face when we act in these roles. I don’t speak for anyone else, but in my own personal instance, I start and end as a person with diabetes. I may work for diabetes organisations, have my own health consultancy, and spend a lot of time volunteering in the diabetes world, but what matters at the end of the day and what never leaves me is that I am a person living with diabetes. And I would expect that is how others would regard me too, or at least would remember that. It’s been somewhat shocking this year to see that some people seem to forget that.

Final thoughts…

Recently when I was in New York at Breakthrough T1D headquarters, I realised just how many people there are in the organisation living with the condition. It’s somewhat confronting – in a good way! – to realise that there are so many people with lived experience working with – very much with – the community. And it’s absolutely delightful to be surrounded by people with diabetes at all levels of the organisation – including the CEO. But you don’t have to have diabetes to work in diabetes. Some of the most impactful people I’ve worked with didn’t live with the condition. But being around people with diabetes as much as possible was important to them. It’s really easy to do when people with diabetes are on staff! I first visited the organisation’s office years ago – long before working with them – to give a talk about language and diabetes. One of the things that stood out for me back then was just how integral lived experience was at that organisation. From the hypo station (clearly put together by PWD who knew they would probably need to use the supplies!) to the conversations with the team, community was in the DNA of the place. As staff, I’ve now visited HQs a few times, and I’ve felt that even more keenly. Walking through the office a couple of weeks ago, I saw this on the desk of one of my colleagues and I couldn’t stop laughing when I saw it. IYKYK – and we completely knew!

DISCLOSURES (So many!)

I was part of the group working on the AID Consensus Statement, and the National AID Access Summit that led to the statement.

I am on the team working on the Language Matters Diabetes and Pregnancy initiative.

I was a co-author on the article, Living between two worlds: lessons for community involvement.

I am an investigator on the HypoPAST study.

My contribution to all these initiatives has been voluntary

I am a representative on the ATIC community group, for which I receive a gift voucher honorarium after attending meetings.

I work for Breakthrough T1D (formerly JDRF).

Imagine a community where people come together to make things happen. You don’t have to look far, really. Just look at the diabetes community!

Here’s something new from some folks (Jazz Sethi, me and Partha Kar) who are desperately trying to reshape the way diabetes is spoken about, and how fortunate I feel to have been involved in this project!

The thinking behind these particular language resources is to truly centre the person with diabetes when thinking about communication about the condition. In this series, we’ve highlighted three groups where we know (because these are the discussions we see in the diabetes community) language can sometimes be stigmatising and judgemental. This isn’t a finger-pointing exercise. Rather it’s an opportunity to highlight how to make sure that the words, images, body language – all communication – doesn’t impact negatively on people with diabetes.

A massive thanks to Jazz and Partha. Working together, and with the community, to create and get these out there has been a joy. (As was sneaking into the ATTD Exhibition Hall before opening time so we could get a coffee and find a comfortable seat to work before the crowds made their way in!) And a super extra special nod to Jazz who pulled together the design and made our words look so bright pretty! And a super, super, super special thanks to Jazz for designing my new logo which is getting its first run on the back of these guides.

You can access these and share directly from the Language Matters Diabetes website. These don’t belong to anyone other than the diabetes community, so please reach out if you would like to provide any commentary or be involved in future efforts. There’s always more to do!

How are two separate Twitter incidents in the DOC related when one was started after someone without diabetes made some pretty horrid comments about diabetes and the other was a conversation diminishing the whole language matters movement to something far less significant and important than what it is truly about.

Let’s examine the two.

EXHIBIT A

Sometime over the weekend, someone I’d never heard of came out with some pretty stigmatising commentary about diabetes. This person doesn’t have diabetes. But hey – joking about diabetes is perfectly okay because, why not? Everyone else does it. Jump on the bandwagon!

She deleted her original tweet after several folks with diabetes pointed out just how and why she was wrong. And also, how stigmatising she was being.

In lands where all is good and happy, that would have been the end of it. We would have moved on, lived happily for a bit, until the next person decided to use diabetes as a punchline.

But no. She decided to double down and keep going. It was all bizarre and so out of touch with what the reality of diabetes is, but perhaps the most bizarre and startling of all was her declaration that there is no stigma associated with diabetes. Well, knock me down with a feather because I’m pretty sure that not only is diabetes stigma very real, but I’ve been working on different projects addressing this stigma for well over a decade now.

EXHIBIT B

At the same time this mess was happening, there was a discussion by others in the DOC about being called a person with diabetes versus being called (a) diabetic. I’m pretty sure it was a new conversation, but it may have been the same one that played out last month. And the month before that, and a dozen times last year. Honestly, to me, this conversation is the very definition of bashing my head against a brick wall. If you’ve played in the DOC Twitter playground you would have seen it. It goes something like this:

‘I want to be called diabetic.’

‘I don’t care what others say, I like person with diabetes.’

‘Why should I be told what to call myself?’

‘I am more than my diabetes which is why I like PWD.’

‘My diabetes does define me in some ways, which is why I like diabetic.’

(And a million variations on this. Rinse. Repeat.)

I have no idea why it keeps happening, because I’m pretty sure that at no time has anyone said that people with diabetes should align their language with guidance or position statements to do with language. I’m also pretty sure that at no point in those statements does it say that people with diabetes/diabetics (whatever floats your boat) must refer to themselves in a certain way. And it’s always been pretty clear that those adjacent to (but not living with) diabetes should be guided by what those with lived experience want.

AND it’s also been pointed out countless times that it’s not about single words. It’s about changing attitudes and behaviours and addressing the misconceptions about diabetes. And yet, for some, it keeps coming back to this binary discussion that fails to advance any thinking, or change anything at all.

Is there a great discussion to be had about person-first versus identity-first language? Absolutely. And looking at long-term discussions in the community there are some truly fascinating insights about how language has changed and how people have changed with it. But does it serve anyone to continue with the untrue rhetoric that people interested in language are forcing people with diabetes / diabetics (your choice!) to think one way? Nope. Not at all. It’s untrue, and completely disingenuous.

These two seemingly separate situations are connected. And that is completely apparent to people who are able to step back and step above the PWD / diabetic thing. People who know nothing about diabetes keep punching down because they think diabetes is fair game. And people with diabetes are the ones who are left to deal with these stigmatising and nasty attitudes.

I woke this morning to this tweet from Partha Kar.

I was grateful for the tag here because the frustration Partha has expressed mirrors the frustration I am feeling on the other side of the world.

I don’t know why this keeps coming up, I really don’t. I honestly do think that most people understand that we talk language in relation to stigma and to discrimination and to access. That was how it was addressed at the WHO diabetes focus groups earlier this year. That is how it was addressed at the #dedoc° symposium at ATTD. It is how the discussion flowed in last year’s Global Diabetes Language Matters Summit. Most understand that these issues are far more pressing.

If people want to keep banging a drum about the diabetes versus diabetic thing, that’s fine. But I reckon that many of us have moved well beyond that now as we seek to address ways to change the way people think and behave about diabetes so that we stop being the butt of jokes or collateral of people punching down on Twitter.

Advocacy is a slow burn. I say those words every day. Usually multiple times. I say it to people with diabetes who are interested in getting into advocacy, not to scare them off, but so they understand that things take time. I say it to established advocates. I say it to people I work with. I say it to people in the diabetes world who want to know why it takes so long for change to happen. I say it to healthcare professionals I’m working with to change policy. I mutter it to myself as a mantra.

Slow. Burn.

But then, there are moments where there is an ignition, and you realise that the slow burn is moving from being nothing more than smouldering embers into something more. And when that happens I can’t wipe the smile of my face and I start jumping up and down. Which is what I was doing in my study at home at 2am, desperately trying to make as little noise as possible so as not to wake my husband and daughter who were sounds asleep in other rooms off the corridor.

The World Health Organisation conducted the first of its two focus group sessions for people with diabetes yesterday (or rather for me, early this morning), and I was honoured to be part of the facilitating team for this event. In the planning for the questions that would be discussed in the small break out groups, the WHO team had gone to great pains to workshop the language in the questions so they were presented in a way that would encourage the most discussion possible. That was the start of those embers being stoked.

I think that the attention to how we framed the discussion points meant that people thought about their responses differently.

The topics last night were about barriers to access of essential diabetes drugs, healthcare and technology. Of course, issues including affordability, health professional workforce, ongoing training and education were highlighted. These are often the most significant barrier that needs to be addressed.

But the discussion went beyond this, and time and time again, people identified stigma and misconceptions about diabetes as a significant barrier to people not being able to get the best for their diabetes. It certainly wasn’t me who mentioned language (at least not first), but communication and language were highlighted as points contributing to that stigma.

This recurring theme came from people from across the globe. It was mentioned as a reason for social exclusion as well as workplace discrimination. There was acknowledgement that perceptions of diabetes as being all about personal responsibility has affected how policy makers as well as community responds to diabetes – how serious they see the condition.

In the discussion about diabetes-related complications, the overall language had been changed from ‘prevention’ to ‘risk reduction’ and this was recognised in many of the discussions as a far better way to frame conversations and education about complications. This isn’t new – it was a recurring theme when a focus in the DOC was the hashtag #TalkAboutComplications. I wrote and co-wrote several articles about it, including this piece I co-authored with the Grumpy Pumper for BMJ.

The direction the discussions took were a revelation. No. It was a revolution!

So often at other events and in online debates when language and communication has been raised, conversation has been stalled by people pushing agendas about wanting to be called ‘diabetic’, as if this is the first and only issue that needs to be resolved. That didn’t even come up last night because the people who were highlighting the implications of language understood that when you look at the issues strategically and at a higher level, those details are not what matters.

What matters is looking at Communication with a capital C and understanding its influence. It elevated the discussion so far above the ‘it’s political correctness and nothing more’ that it would have been ridiculous to drag the discussion back to that level.

For years, there has been push back regarding communication because people have not stood back and looked at impact. That has changed.

When I wrote this four years ago highlighting that diabetes’ image problem diabetes – all those misconceptions and wrong ideas about the condition – has led to fewer research dollars, less understanding and compassion from the community, more blame and shame levelled at individuals … it was to emphasise that the repercussions have been significant.

Thankfully as more people started stepping back and considering big picture – health systems, policy, community education – I could see that there were shifts as some people stopped talking about political correctness and started asking what needed to be done to really move the needle. It seems that’s where the very, vast majority of people were during the WHO focus group

This diabetes #LanguageMatters movement stands on the shoulders not of the people who have elevated the issue in the last ten years (although those contributions have been massive!) or the position papers and guidelines that have been published (although those have certainly aided the discussion in research and HCP spaces), but rather, the people in the diabetes community who, for years, knew that language and communication was a driving factor in our care. People like those in the (Zoom) room yesterday.

Looking for more on #LanguageMatters

Click here for a collection of posts on Diabetogenic.

The Diabetes Australia Language Position Statement (Disclosure: I work at Diabetes Australia and am a co-author on this statement.)

The Diabetes Language Matters website which brings together much of the work that has been done globally on this issue. (Shout out to diabetes advocate Jazz Sethi for her work on this.)

DISCLOSURE

I was invited by the WHO Global Diabetes Compact team to be part of the facilitators at the Focus Group on Advancing the Lived Experience of People Living with Diabetes. I am happily volunteering my time.