You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Stigma’ category.

Last week I was in Geneva for the 78th World Health Assembly (WHA78). It’s always interesting being at a health event that is not diabetes specific. It means that I get to learn from others working in the broader health space and see how common themes play out in different health conditions.

It’s also useful to see where there are synergies and opportunities to learn from the experiences of other health communities, and my particular focus is always on issues such as language and communications, lived experience and community-led advocacy.

What I was reminded of last week is that is that stigma is not siloed. It permeates across health conditions and is often fuelled by the same problematic assumptions and biases that I am very familiar with in the diabetes landscape.

I eagerly attended a breakfast session titled ‘Better adherence, better control, better health’ presented by the World Heart Federation and sponsored by Servier. I say eagerly, because I was keen to understand just how and why the term ‘adherence’ continues to be the dominant framing when talking about treatment uptake (and medication taking). And I wanted to understand just how this language was acceptable that this was being used so determinately in one health space when it is so unaccepted in others. This was a follow on from the event at the IDF Congress last month and built on the World Heart Foundation’s World Adherence Day.

While the diabetes #LanguageMatters movement is well established, it is by no means the only one pushing back on unhelpful terminology. There has been research into communication and language for a number of health conditions and published guidance statements for other conditions such as HIV, obesity, mental health, and reproductive health, all challenging language that places blame on individuals instead of acknowledging broader systemic barriers.

I want to say from the outset that I believe that the speakers on the panel genuinely care about improving outcomes for people. But words matter as does the meaning behind those words. And when those words are delivered through paternalistic language it sends very contradictory messages. The focus of the event was very much heart conditions, although there was a representative from the IDF on the panel (more about that later). But regardless the health condition, the messaging was stigmatising.

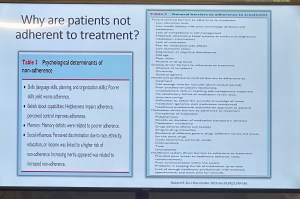

The barriers to people following treatment plans and taking medications as prescribed were clearly outlined by the speakers – and they are not insignificant. In fact, each speaker took time to highlight these barriers and emphasise how substantial they are. I’m wary to share any of the slides because honestly, the language is so problematic, but I am going to share this one because it shows that the speakers were very aware and transparent about the myriad reasons that someone may not be able to start, continue with or consistently follow a treatment plan.

You’ll see that all the usual suspects are there: unaffordable pricing, patchy supply chains, unpleasant side effects, lack of culturally relevant options, varying levels of health literacy and limited engagement from healthcare professionals because working under conditions don’t allow the time they need.

And yet, despite the acknowledgement there is still an air of finger pointing and blaming that accompanies the messaging. This makes absolutely no sense to me. How is it possible to consider personal responsibility as a key reason for lack of engagement with treatment when the reasons are often way beyond the control of the individual?

The question should not be: Why are people not taking their medications? Especially as in so many situations medications are too expensive, not available, too complicated to manage, require unreasonable or inflexible time to take the meds, or come with side effects that significant impact quality of life. Being told to ‘push through’ those side effects without support or alternatives isn’t a solution. It is dismissive and is not in any way person-centred care.

The questions that should be asked are: How do we make meds more affordable, easier to take, and accessible? What are the opportunities to co-design treatment and medication plans with the people who are going to be following them? How do we remove the systemic barriers that make following these plans out of reach?

One of the slides presented showed the percentage people with different chronic conditions not following treatment. Have a look:

My initial thought was not ‘Look at those naughty people not doing what they’re told’. It was this: if 90% of people with a specific condition are not following the prescribed treatment plan, I would suggest – in fact, I did suggest when I took the microphone – the problem is not with the people.

It is with the treatment. Of course it is with the treatment.

The problem with the language of adherence is that it frames outcomes through the lens of personal responsibility. It absolves policy makers of any duty to act and address the structural, economic and systemic barriers that prevent people from accessing and maintaining treatment. Why would they intervene and develop policy if the issue is seen as people being lazy or not committing to their health?

And it means the healthcare professionals are let off the hook. It assumes they are the holders of all knowledge, the giver of treatment and medications, and the person in front of them is there do what they are told.

There is no room in that model for questions, preferences, or complexity. There is no room for lived experience. There are no opportunities for co-design, meaningful engagement or developing plans that are likely to result in better outcomes.

When the room was opened up to questions, I raised these concerns, and the response from the emcee was somewhat dismissive. In fact, she tried to shut me down before I had a chance to make my (short) comment and ask a question. I’ve been in this game long enough to know when to push through, so I did. I also don’t take kindly to anyone shutting down someone with lived experience, especially in a session where our perspective was seriously lacking. Her response was to suggest that diabetes is different. I suggest (actually, I know) she is wrong.

And I will also add: while there was a person with lived experience on the panel, they were given two questions and had minimal space to contribute beyond that. I understand that there were delays that meant they arrived just in time for their session, but they were not included in the list of speakers on the flyer for the event while all the health professionals and those with organisation affiliation were. There comments were at the very end of the session, and I was reminded of this piece I wrote back in 2016 where health blogger and activist Britt Johnson was expected to feel grateful that the emcee, who had ignored her throughout a panel discussion, gave her the last five minutes to contribute.

Collectively this all points to a bigger issue, and we should name that for what it is: tokenism.

I didn’t point this out at the time, but here is a free tip for all health event organisers: getting someone to emcee who is a journalist or on-air reporter does not necessarily a good emcee make. Because when you have someone with a superficial understanding of the nuance and complexity involved in living with a chronic health condition, or understand the power dynamics and sensitivities required when facilitating a conversation about long-term health conditions, you wind up with a presenter who may be able to introduce speakers, but you miss out on meaningful and empathetic framing of the situation. There are people with lived experience who are excellent emcees and moderators, and bring that authenticity to the role. Use them. (Or get someone like Femi Oke who moderated the Helmsley + Access to Medicine Foundation session later in the day. She had obviously done her homework and was absolutely brilliant.)

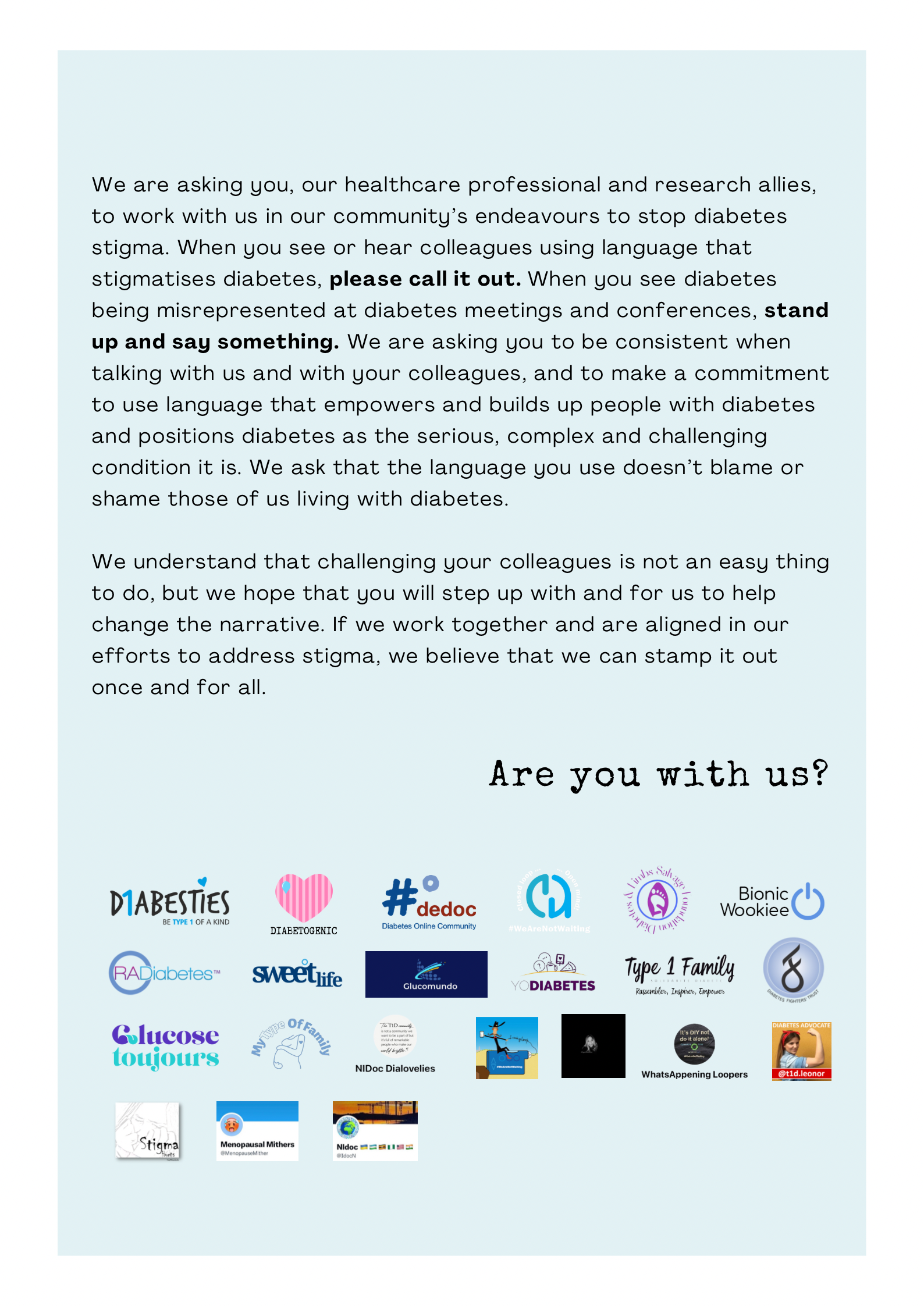

I know that there has been a lot of attention to language in the diabetes space. But we are not alone. In fact, so much of my understanding has come from the work done by those in the HIV/AIDS community who led the way for language reform. There are also language movements in cancer care, obesity, mental health and more. And even if there are not official guidelines, it takes nothing to listen to community voices to understand how words and communication impact us.

So where to from here? In my comment to the panel, I urged the World Heart Foundation to reconsider the name of their campaign. Rather than framing their activities around adherence, I encouraged them to look for ways to support engagement and work with communities to find a balance in their communications. I asked that they continue to focus on naming the barriers that were outlined in the presentations, and shift from ‘How to we get people to follow?’ to ‘How do we work with people to understand what it is that they can and want to follow?’.

Finally, it was great to see International Diabetes Federation VP Jackie Malouf on the program on the panel. She was there to represent the IDF, but also brought loved experience as the mother of a child with diabetes. The IDF had endorsed World Adherence Day and perhaps had seen some of the public backlash about the campaign and the IDF’s support. Jackie eloquently made the point about how the use of the word was problematic and reinforced stigma and exclusion, and that there needs to be better engagement with the community before continuing with the initiative.

One of the things of which I am most proud is seeing how the language matters movement has really made people stop and think about how we communicate about diabetes. Of course, there’s still a long way to go, but it is very clear that there have been great strides made to improve the framing of diabetes.

One area where there has been a noticeable difference is at diabetes conferences. I’m not for a moment suggesting that there is never negative language used at conferences and meetings, but the clangers stand out now and are likely to be highlighted by someone (i.e. #dedoc° voices) in the audience.

Earlier this month, the 75th IDF World Congress was held in Bangkok. Sadly, there was no livestream of the Congress, but it’s a funny thing when you have a lot of friends and colleagues (i.e. #dedoc° voices) in attendance. It meant that I had my own livestream. Sadly, the majority of what I was being sent were the language clangers.

But let’s step back a week or so to before the Congress even started. I was feeling horrendous and my brain was in a foggy, virus haze, yet I still managed to be indignant and vent at the horrendously titled ‘World Adherence Day’ which was being ‘celebrated’ on 27 March. Here is my post from LinkedIn, which has been viewed close to 12,000 times:

What I didn’t say in my post was that the IDF had eagerly endorsed the day with a media release and social media posts. My LinkedIn post took all my energy for that day, and I didn’t get a chance to follow up with the IDF. Plus, I assumed their attention would have been focused very much on the upcoming Congress.

Also, I hoped that it was a one-off misstep. I mean, surely the organisation had learnt its lesson after the Congress in South Korea when I boldly challenged incoming-president Andrew Boulton for his suggestion that people with diabetes need some ‘fear arousal’ to understand how serious diabetes is. You can see the video of my response to that at the end of this post and read the article I co-authored (Boulton was another co-author) about language here.

Alas, I was wrong. Just days before the Congress started, I saw flyers for this session shared online:

I was horrified and commented on a couple of the posts I saw. I was surprised to see some responses from advocates which amounted to ‘We can deal with it when we get there.’ Here are reasons that isn’t good enough. Firstly – not everyone is there, so all they see is the promotional of an event, comfortably using stigmatising language. It suggests that this language and the meaning behind it is okay. The discussion shouldn’t be happening after the fact. In fact, the question we should be asking is: HOW did this even happen? Where were the people with lived experience on the organising committee of the Congress speaking up about this? Did they get to see it before it was publicised? And how did the IDF miss it? This is, after all, the organisation that launched a ‘Language Philosophy’ document in 2014 (which sadly seems to be unavailable online today). It’s also the organisation that has invited me to give a number of talks about the importance of using appropriate and effective communication to IDF staff, attendees of the Young Leaders Program and as an invited speaker at a number of Congresses.

A major sponsor at the IDF Congress seemed to be very excited about the word adherence. In fact, it appeared over and over in their materials at the Congress. Here is just a couple of their questionable messaging sent to me by people (i.e. #dedoc° voices) attending the Congress:

I will point out that the IDF obviously understands the impact of stigma on people with diabetes and the harm it causes. There were sessions at the Congress dedicated to diabetes-related stigma and how to address it. In fact, I had been invited to give one of those talks. But what is disappointing is that despite this, terminology that contributes to stigma is being used without question.

I wasn’t at the Congress but from what I saw there was indeed a vibrant lived experience cohort there. #dedoc° had a scholarship program, and, as usual, there was a Living with Diabetes stream. However, I will point out that the LWD stream was not chaired by a grassroots advocate as has been the case for all previous LWD streams. It was chaired by a doctor with diabetes and while I am in no way trying to delegitimise his lived experience, I am unapologetically saying that this is a backwards step by the IDF. When there is an opportunity for a person with diabetes who is not also a health professional is given to a health professional or a researcher, that’s a missed opportunity for a person with diabetes. There were seven streams at the IDF Congress. All except for one are 100% chaired by clinicians and researchers. Only the LWD stream is open to PWD. I know that when I chaired the stream, the four members of the committee were diligent about looking through the entire and identifying any sessions that could be considered problematic for people with diabetes. It appears that didn’t happen this time.

All of this points to a persistent disconnect. It is undeniable that the language matters movement is growing, but it is still not embedded across the board—even within organisations that should know better. If we are serious about addressing stigma and centring lived experience in diabetes care, then language can’t be an afterthought or a debate to have after the posters are printed and the sessions are underway. It must be part of the planning and the review process. The easiest way to connect the dots is to ensure the lived experience community is not only present, but also listened to, respected, and in positions to influence and lead. We are long past the point where being in the room or offered a solitary seat is enough – the room is ours; we are the table.

Postscript:

I have written extensively on why language – and in particular the word ‘adherence’ – is problematic. It’s old news to me and to many others as well. This piece isn’t about that. But if you want to know why it’s problematic, here’s an old post you can read.

Disclosures:

I was an invited to give a talk about diabetes-related stigma at the IDF Congress in Bangkok, but disappointingly, had to cancel my attendance due to illness. The invitation included flights and accommodation as well as Congress registration. I was also on the program for two other sessions and was due to present to the YLD Program.

Other IDF disclosures: I have been faculty for the YLD Program for the last 10 years; I chaired the LWD Stream at the 2019 Congress and was deputy chair of the 2017 Congress.

It’s never hard to find a source of diabetes stigma. Because sadly, it’s all around us. And right now, the source seems to be much of the discussion about the report from the Australian Parliamentary Inquiry into Diabetes.

Yes, I was very excited about the report last week when I was writing about the recommendations and accompanying content about increasing access to pumps and AID systems. That was incredible news, and it was terrific to see that the community-led efforts were met with such a positive outcome.

But the messaging more broadly hasn’t been so great and it’s very disappointing.

Disappointing, but not surprising really. After all, the inquiry was for diabetes and obesity. Last week, I said that people with T2D deserve the same attention as people with T1D when it comes to advocacy efforts and campaigns. Well, so do people living with obesity. When the inquiry was first announced, I remember reading through its terms of reference and feeling my heart sink. These are two separate and equally important health issues that need focused attention. And within that, diabetes itself comprises different types; again, all equally important and requiring specific attention.

But instead of giving diabetes the attention it deserved with an inquiry purely focused on highlighting what is needed to improve outcomes for those of us living with the condition and enhancing the health system to better serve us, we were given an inquiry that conflated two separate and significant health conditions. Something was going to get lost in this. And it seems that is diabetes.

Since the report was launched on Wednesday, a lot of media coverage has focused on one specific recommendation: the sugar tax. That was what was on the front page of The Australian, a segment on the Project and in a number of radio interviews. Also mentioned in this coverage was the recommendation about junk food advertising to children. As you can imagine, the commentary from the community has been pretty horrid and completely misinformed. If ever there was a time for not reading the comments, this is it.

I completely agree that a sugar tax is a good idea and have been saying so for years. I also believe that junk good advertising should be banned completely, especially for children, starting with TV and online advertising and extending to sponsorship of children’s sporting activities. Again, I have been involved in initiatives involving this for years. One of the reasons these measures are important is that they make healthier choices more accessible, which can reduce the risk of people developing obesity. And yes, obesity is a risk factor for T2D. However not everyone who is obese will develop T2D and not everyone who has T2D is obese. Yet this nuance is missed completely with simplistic messaging and grouping the two together.

And this nuance is important. As is pointing out that obesity is also a risk factor for many other conditions as well such as several types of cancer, liver disease, heart attack and stroke, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, osteoarthritis, sleep apnoea, mental health conditions, fertility problems and pregnancy problems. Not only T2D, so why is it included in an Inquiry about diabetes?

I shouldn’t be surprised by the media missing the mark completely, but that doesn’t mean that it doesn’t anger and upset me. Because efforts can be made to try to minimise harm and stigma from misreporting. I was asked to contribute to a media release this week about the AID work and I made it very clear that I would not be involved in anything where messaging could be seen as stigmatising. I provided a copy of language position statements and asked to see the release before it went out to make sure that it all aligned. I pointed out to the PR agency that I would publicly call out any media that came from this release if it was in any way stigmatising about any type of diabetes. Sadly, I don’t think there has been that level of care across PR and media groups. Without that care and attention the stigmatising tropes about diabetes, in particular T2D, are in overdrive.

But it’s not just the media. In the report itself, there is this statement: ‘There is a huge burden being placed on health resources by people with Type 2 diabetes’, a statement that clearly blames people with T2D for needing to use our underfunded, under-resourced, understaffed healthcare system. Absolutely no recognition of non-modifiable risk facts or social determinants of health. More stigma. More misinformation. More throwing people with T2D under the bus. And this impacts on all types of diabetes, whether we like it or not.

I really wish that as we are all tripping over ourselves to highlight this Inquiry report, we also stop to think about the messages about diabetes we are setting free into the world. So far, very little of what I have seen hasn’t made me cringe. Far too much has been stigmatising and harmful. We all have a role to play in ensuring that we do not contribute to diabetes stigma, especially when participating in commentary about and the media circus of a new shiny report being launched.

On November 14, the world will literally light up in blue to celebrate World Diabetes Day. And here in Melbourne, an event highlighting one of the most important issues in diabetes today will be held. The entire event will be dedicated to how the global diabetes community is coming together to work to #EndDiabetesStigma. And you can be there!

I’m delighted to be sharing the hosting seat with Dr Norman Swan, physician, journalist and host of Radio National’s Health Report. A veritable A-Team of people from the international diabetes community will be part of the event, sharing their experiences of diabetes stigma and why efforts to end it are so necessary and timely. There will be representatives from the global lived experience community, diabetes organisations and health professionals and researchers. You really don’t want to miss it!

For those able to attend in person, you’ll have a chance to catch up with diabetes mates. Any chance for opportunistic peer support is a great thing and I’m so pleased that I’ll be seeing diabetes friends that I’ve not seen for a very long time.

This isn’t only for Melbourne locals. There will be a livestream for people around the world to watch, share and be part of on social media. It’s free to attend and will be a great opportunity to see the diabetes world come together on a day dedicated to us!

All too frequently, when talking about meaningful lived experience engagement, I hear about ‘Hard to Reach Communities’. A number of years ago, I called rubbish on that, putting a stop to any discussion that used the term as a get out of jail free card to excuse lack of diversity in lived experience perspectives.

‘People with type 2 diabetes don’t want to be case studies’ or ‘Young people with diabetes don’t respond to our call outs for surveys’ or ‘People from culturally and linguistically diverse communities won’t share their stories’ or ‘Folks in rural areas don’t come to our events’. These are just some real life examples I heard when asking why there was no diversity in the stories I was seeing.

See how the blame there is all on the people with diabetes? They don’t want, don’t respond, won’t share, won’t attends. It’s them. They’re the problem. It’s them.

I stood on stage at EASD in Stockholm last year and challenged the audience to stop using the term ‘hard to reach’. Because that’s not the case at all. The truth is that in most cases, the same old, uninventive methods are always employed. And those methods only work for a very narrow segment of the community.

I recently heard someone begrudge that all applicants who responded to a recent call out for a new committee were the same: white, had type 1 diabetes, city-dwelling. ‘Of course they are,’ I said. ‘That’s the group that loves a community advisory council and responds to an expression of interest call out on socials. They are able to attend meetings when they are scheduled, are confident to speak up and are willing to share their story, because they probably have before and received positive feedback for doing so Plus, they’re expecting everyone else at the table will look and sound just like them.’

But the lack of diversity isn’t the problem of the people who didn’t respond. It’s the problem of whoever is putting out a call and expecting people to reply because that’s how it’s Always Been Done.

This was a discussion at a meeting during last week’s American Diabetes Association Scientific Sessions. The #dedoc° voices were meeting with the ADA’s Chief Scientific Officer, Dr Bob Gabbay, and Vice President in Science & Health Care, Dr Nicole Johnson. The question about how to reach a broad audience was asked. At #dedoc°, efforts have been made to attract a diverse group of people to our scholarship program, and have, to a degree there as been some success. A glance at any one of the #docday° events, or scholarship alumni will see people who had not previously been given a platform within the diabetes community. But there is always more than can be done.

The discussion in that meeting at ADA mirrored many that happened throughout the week. And it’s not surprising that US diabetes advocate Chelcie Rice came up with the perfect way to explain how to do better at engaging with the who have previously been dismissed as ‘hard to reach’. He said: ‘You can’t just put pie in the middle of the table. Deliver the pie to where they are.’ And he’s right. Those tried and true methods that work for only one narrow segment of the community have been all about putting pie in the middle of the table, knowing that there will be some people ready with a plate and a fork. But a lot of people are not already at the table, or comfortable holding out their plate. Or maybe they don’t even like that pie. But we never find out because no effort is really made.

Chelcie once said ‘If you’re not given a seat at the table, bring your own chair‘ and I’ve repeated that quote dozens, if not hundreds of times. And his words ring very true for people like me who have felt very comfortable dragging my own chair, and one for someone else and insisting that others scramble to make room for us. But that metaphorical table isn’t enough anymore. Not everyone wants to sit at a table and we need to stop expecting that. Instead, it’s time to find people where they are – the places, the settings, the environments they feel comfortable and at home. That’s how you do engagement.

Imagine a community where people come together to make things happen. You don’t have to look far, really. Just look at the diabetes community!

Here’s something new from some folks (Jazz Sethi, me and Partha Kar) who are desperately trying to reshape the way diabetes is spoken about, and how fortunate I feel to have been involved in this project!

The thinking behind these particular language resources is to truly centre the person with diabetes when thinking about communication about the condition. In this series, we’ve highlighted three groups where we know (because these are the discussions we see in the diabetes community) language can sometimes be stigmatising and judgemental. This isn’t a finger-pointing exercise. Rather it’s an opportunity to highlight how to make sure that the words, images, body language – all communication – doesn’t impact negatively on people with diabetes.

A massive thanks to Jazz and Partha. Working together, and with the community, to create and get these out there has been a joy. (As was sneaking into the ATTD Exhibition Hall before opening time so we could get a coffee and find a comfortable seat to work before the crowds made their way in!) And a super extra special nod to Jazz who pulled together the design and made our words look so bright pretty! And a super, super, super special thanks to Jazz for designing my new logo which is getting its first run on the back of these guides.

You can access these and share directly from the Language Matters Diabetes website. These don’t belong to anyone other than the diabetes community, so please reach out if you would like to provide any commentary or be involved in future efforts. There’s always more to do!

On Sunday, one of those annoying diabetes things happened – a kinked insulin pump cannula, subsequent high glucose levels followed by a little glucose wrangling tango where, instead of rage blousing, I tried to gently guide my numbers back in-range. I thought about how frustrating diabetes can be – unfairly throwing curve balls at us even when we are doing ‘all the right things’. And so, I used this little story for a post on LinkedIn to illustrate why I am so dedicated to making sure that stories like this are heard and lived experience is centred in all diabetes conversations.

Meanwhile, anyone who has even the barest of little toes dipped in the water of the diabetes community would have heard about Alexander Zverev being told by French Open officials that he was not permitted to take his insulin on court. He was expected to inject off court and, according to Zverev, was told ‘looks weird when I [inject] on court’. Insulin breaks would be considered as toilet breaks.

What’s the connection between this story and my LinkedIn story? Absolutely none. Except there kind of is.

I’m not about to write about sports or try to connect my story with that of a top-ranking tennis player. That would be totally out of my lane. (The couple of years of tennis I took when I was in grades five and six give me no insight into life of a tennis player.)

However, when it comes to discussing diabetes and the stigma surrounding it, I’m definitely in my lane. I understand and am very well-versed when it comes to talking about the image problem diabetes faces and how that fuels the stigma fire.

The response from the diabetes community when the Zverev story broke. Most people were incredibly supportive of the tennis player and rightfully indignant of the incident. JDRF UK responded swiftly with an open letter to the French Open organisers, eloquently highlighting why their ruling needed to be changed. And changed it was.

My LinkedIn post was shared a few times and there were comments from people saying that these stories help others better understand our daily challenges and work to cut through a lot of the misconceptions about diabetes.

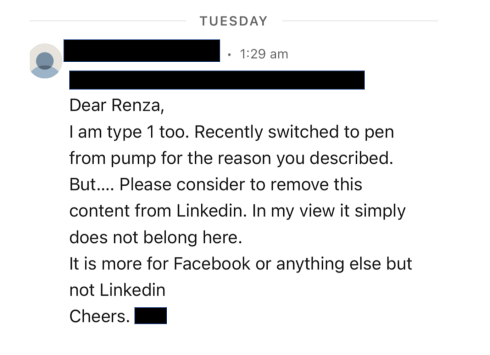

And then there was this direct message:

I bristled as I read it. My initial response was ‘How dare this man try to tell me what I can and can’t post on LinkedIn. Who is he to tell me what I can and can’t share?’ I snapped a reply back to him where I pointed out: ‘…I am a diabetes advocate, working to change attitudes and raise awareness about living with diabetes. My post belongs here on LinkedIn as it very much aligns with the work I do.’

But I haven’t been able to stop thinking about it because as problematic as it is for someone trying to silence what people with diabetes share online, there was more that was troubling me.

The idea that diabetes is a topic only appropriate in certain contexts and should be hidden away from others reinforces shame. Suggesting work settings are not the place to talk diabetes plants that seed that diabetes, and people with diabetes, could be liabilities in the workplace. Talking about diabetes on LinkedIn – a platform for business and workplace networking – is relevant because people with diabetes exist in business and workplaces, and the reality is that diabetes sometimes interferes with our work. Which is perfectly okay. Last week, I needed to refill my pump during a meeting. So, I let others on the call know what I was doing and carried on. On another day, I was recording a short video about a research program and after take 224 realised I needed to treat a hypo and did so. I shouldn’t need to feel that these aspects of daily life with diabetes are only allowed to happen out of view.

Essentially, this is what Alexander Zverev was being asked to do at his workplace: hide away when he needed to perform a task that keeps him alive, as if there is something shameful and disgusting about it. In my mind, this top ranked tennis player playing in a Grand Slam competition should be commended. I mean, any tennis player who does that is remarkable. Zverev does it and then goes about performing the duties of a pancreas. His opponents don’t have to do that! Their pancreas doses out the perfect amount of insulin without any help. Talk about an unfair advantage!

Not everyone wants to talk diabetes with others and that’s fine. But those of us who are happy to speak about and ‘do diabetes’ wherever we are shouldn’t feel that we are doing anything wrong. Diabetes stigma exists because there are so many wrong attitudes about diabetes. It’s insidious and it’s damaging. It erects barriers creating a climate of shame and perpetuates misconceptions that lead to ignorance. And it pressures us to hide away the realities of diabetes, as if there is something to be ashamed of. But there is nothing shameful about living with diabetes. There is nothing shameful about injecting insulin on Centre Court at Roland-Garros, or sharing frustrations on LinkedIn. Or anywhere else. Diabetes has a place wherever your workplace might be. Stigma, however, does not.