You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘DIYAPS’ category.

Do you remember life before diabetes? It’s getting harder and harder for me to. I had 24 years without diabetes, and occasionally, I’ll look at a photo from the BD years and think about how much simpler my days were.

Today, I’m wondering how much I remember diabetes before I started using automated insulin delivery (AID). It’s been eight years. Eight years of Loop. Happy loopiversary to me! Diabetes BL (before Loop) felt heavier. And scarier. I remember those months just after I started looping and how different things felt. I remember the better sleep and the increased energy. I remember a lightness that I hadn’t experienced since I was diagnosed.

That’s now my “diabetes normal”. Life with Loop is simply easier than life BL. On the very rare occasions I’ve had to DIY diabetes, it’s been a jolt as I’ve realised just how truly bad I am at diabetes. Embarrassingly bad.

While there was a stark difference back then between people who were using DIYAPS and those who were using interoperable devices on the market, today that difference is less. AID systems are not just for people who choose to build one for themselves. These days, it’s so great to know that there are commercial systems available which means more people have access to AID. We can debate which algorithm is better or whether a commercial or an open-source system is better, but I think that’s a little pointless. If people are doing less diabetes and feeling happier, better and less burdened, it doesn’t matter what they’re using. Your diabetes; your rules!

Eight years on, and despite there being commercial systems I could access, I’ve decided to keep using Loop – the same system I started on 8 years ago. The changes I’ve made are the devices with which I am using Loop. My pink Medtronic pump has been retired, along with the Orange Link (which was obviously in a pink case). Instead, I now use Omnipod, a single device instead of two which has further simplified my diabetes. It’s also meant not worrying about a working back up Medtronic pump, and it means carrying less bulky supplies when travelling.

These may all seem like little things, but they add up.

My decision to not move to a commercial system has been based on a couple of different reasons. I always said that I wouldn’t move to something that required a trade-off whereby any of the convenience of Loop was compromised. I’ve been blousing from my iPhone or Apple watch since 2017, and I refused to let that go. In my mind, having to wrangle my pump from my bra or carry an additional PDM to bolus was a step backwards. Of course, this is now available on some commercial systems, and it’s been super cool to see diabetes friends have access to something that does make diabetes a little less intrusive.

The customisability of Loop has meant that my target levels are set by me and me alone. The lower limit on commercial systems is not what I like mine set at. I wasn’t prepared to sacrifice the flexibility of personalised settings fora one-size-fits-all approach.

I do understand that there are pros to having a commercial system. Having helplines to trouble shoot and customer support on call is certainly a positive. Knowing that an annual Loop rebuild (always anxiety inducing because …well, technology?) is upcoming is stressful. And the worry that the update will break something that’s been working perfectly.

And yet, measure for measure, the decision to continue to use Loop has been very easy.

I still thank the magicians behind open-source technologies for their brilliance and generosity every single day. I’m grateful for the algorithm developers, the people who have written step by step instructions that even I can follow, and I am so thankful for the people who have tried to make devices more affordable. I believe that device makers do genuinely want to make diabetes simpler and help ease the load of diabetes. But in my mind, it’s undeniable that user-led developments have been more successful in actually making diabetes easier. These magicians know firsthand just what it means to claw back from diabetes.

In the end, the goal for me has always been clear: I want diabetes to intrude in my life as little as possible, and I will avail myself of anything that helps. It’s why I continue to use an Anubis even though there is no out of pocket cost for G6 transmitters. Using an Anubis means I change my sensor when it’s getting spotty, not when the factory setting insists, and the transmitter last six instead of three months. See? Fewer diabetes tasks. Less diabetes. That’s the whole point. (And it’s also why I’m hesitant about moving to G7)

When I try to quantify how much less diabetes, I just come back to Justin Walker and his presentation at Diabetes Mine’s DData back in 2018 when he said ‘By wearing Open APS, I save myself about an hour a day not doing diabetes’. Eight years down the track, that’s 2,922 hours I’ve gained back. That’s almost 122 days. It may be thirty seconds here, a minute there. But it adds up. And that time is better in my pocket than in diabetes’.

And so, here I am. Eight years on. With diabetes in the background as much as it can be with the tools I have available to me. I still really don’t like diabetes. I still really resent it takes up the time and brain space it does, and I still want a cure for all of us. Damn, we deserve that.

But in the meantime, I’m going to keep leaning into what the community has done for the community and know how lucky I am to benefit from that knowledge and expertise. Never bet against the T1D community. We know exactly what diabetes takes from us every day. And exactly what it takes to give some of it back.

More on my experiences with Loop

That time I scared the hell out of healthcare professionals

What looping on holidays looks like

A list of how Looped changed my diabetes life (and all of it is still relevant today!)

Postscript

As ever, I’m very aware of my privilege. Access to AID is nowhere near where it should be. If we look at the Australian context, insulin pumps remain out of range for so many people with T1D thanks to outdated funding models. Remember the consensus statement developed last year? And beyond our borders, technology access varies significantly. As a diabetes community, we are not all beneficiaries from this tech until every single person with diabetes has access. And that starts with affordable, uninterrupted access to insulin, right through to the most sophisticated AID systems, to preventative treatments, to cell therapies.

‘Why would you bet against the type 1 community?’ That was a question asked in a session at the ISPAD conference a couple years ago. It wasn’t someone with T1D drawing attention to the community. Instead, it was said by someone working in global health who had seen the remarkable efforts such as the #WeAreNotWaiting movement and grassroots, peer-led education initiatives in low-income countries. These efforts have driven change and improved lives of people with diabetes. They have been led by those with lived experience and supported by other diabetes stakeholders. But the starting point is people directly affected by diabetes identifying a problem, solving it and leading the way. In the history of diabetes – from the first home glucose meters, to building systems leveraging off existing technologies, to global advocacy movements – community powered initiatives have been a driving force for change.

And so, here we are today, coming together once again to advocate for better equity and fairness for all people with type 1 diabetes, this time in Australia, and this time advancing access to automated insulin delivery devices (AID).

Insulin pump funding is broken. AID is standard care and yet far too many people are left unable to use the tech because of how pumps are funded in Australia. Right now, unless a person with T1D has the right level of private health insurance, or meets the criteria for the Insulin Pump Program, they must find the funding for an insulin pump. That needs to change.

We know how to do this in Australia. The reason that pump consumables are on the NDSS is thanks to community advocacy efforts back in the early 2000. And more recently massive community noise helped to get CGM onto the NDSS for all Australians. Of course, these wins worked because everyone was involved in advocacy: people with lived experience of diabetes, healthcare professionals and HCP professional groups, researchers, diabetes community groups and organisations and industry. What a lot of noise we can make when we’re singing from the same song sheet!

Right now, attentions are razor focused on improving access to automated insulin delivery systems because the evidence is clear: AID reduces diabetes distress, improves quality of life, and (for those who like numbers!), help with glucose levels. And as an added bonus for the bean counters – it’s a smart, cost-effective investment for our health system.

If AID is standard care, financial barriers preventing people from accessing it need to be eliminated.

And that’s where we would love your help.

Please sign and share the petition that has been started by Dr Ben Nash and supported by a group of people with T1D (including me). Petitions are a great way to get people talking and interested in a topic. It builds momentum and helps contribute to whole of community conversations. While we know the T1D community is already on board, we’ve now seen a number of HCPs, community groups and diabetes organisations share and promote the petition and are keen to get involved with broader advocacy efforts. That’s pretty cool!

Postscipt:

Understandably, there are questions about why this work is specific to T1D technology access. That’s a fair question and I think that our very own Bionic Wookiee provided an excellent explanation of that when he said this in a social media post earlier this week:

‘AID systems were developed for T1D (where they can track all the insulin going into the system without having to cope with the body’s variable insulin generation). So right now they mainly apply to T1D…

Expanding CGM and pump access to people with other forms of diabetes than just T1D is important for the future. Having wider access to AID for the T1D population will be a beach-head for that.‘

And in a conversation I had about this with UK diabetologist Partha Kar yesterday he cautions that there needs to be a starting point because the sheer numbers of diabetes can be daunting and tend to scare policy makers. He also points out that when it comes to outcome modifying interventions, technology is THE thing in T1D, whereas in other types of diabetes there are other options. I’ll add that those other options often have stronger evidence which is why they already have funding.

Throughout ATTD I got to repeatedly tell an origin story that led us to this year’s #dedoc° symposium. I’ve told the story here before, but I’m going to again for anyone new, or anyone who is after a refresher.

It’s 2015 and EASD in Stockholm. A group of people with diabetes are crowded together in the overheated backroom of a cafe in the centre of the city. Organising and leading this catch up is Bastian Hauck who, just a few years earlier, brought people from the german-based diabetes community together online (in tweet chats) and for in person events. His idea here was that anyone with diabetes, or connected to the conference, from anywhere in the world, could pop in and share what they were up to that was benefitting their corner of the diabetes world. I’ll add that this was a slightly turbulent time in some parts of the DOC in Europe. Local online communities were feeling the effects of some bitter rifts. #docday° wasn’t about that, and it wasn’t about where you were from either. It was about providing a platform for people with diabetes to network and share and give and get support.

And that’s exactly what happened. Honestly, I can’t remember all that much of what was spoken about. I do remember diabetes advocate from Sweden, Josephine, unabashedly stripping down to her underwear to show off the latest AnnaPS designs – a range of clothing created especially to comfortably and conveniently house diabetes devices. It won’t come as a surprise to many people that I spoke about language and communication, and the work Diabetes Australia was doing in this space and how it was the diabetes community that was helping spread the word.

I also remember the cardamom buns speckled with sugar pearls, but this is not relevant to the story, and purely serving as a reminder to find a recipe and make some.

So there we were, far away from the actual conference (because most of the advocates who were there didn’t have registration badges to get in), and very separate from where the HCPs were talking about … well … talking about us.

Twelve months later EASD moved to Munich. This time, Bastian had managed to negotiate with the event organisers for a room at the conference centre. Most of the advocates who were there for other satellite events had secured registrations badges, and could easily access all spaces. Now, instead of needing to schlep across town to meet, we had a dedicated space for a couple of hours. It also means that HCPs could pop into the event in between sessions. And a few did!

This has been the model for #docday° at EASD and, more recently, ATTD as well. The meetups were held at the conference centre and each time the number of HCPs would grow. It worked! Until, of course COVID threw a spanner in all the diabetes conference works. And so, we moved online to virtual gatherings which turned out to be quite amazing as it opened up the floor to a lot of advocates who ordinarily might not be able to access the meetings in Europe.

And that brings us to this year. The first large international diabetes conference was back on – after a couple of reschedules and location changes. And with it would, of course, be the global #dedoc° community, but this time, rather than a satellite or adjacent session, it would be part of the scientific program. There on the website was the first ever #dedoc° symposium. This was (is!) HUGE! It marks a real change in how and where people with diabetes, our stories and our position is considered at what has in the past been the domain of health professionals and researchers.

When you live by the motto ‘Nothing about us without us’ this is a very comfortable place to be. Bastian and the #dedoc° team and supporters had moved the needle, and shown that people with diabetes can be incorporated into these conferences with ease. The program for the session was determined by what have been key discussions in the diabetes community for some time: access, stigma and DIY technologies. And guess what? Those very topics were also mentioned by HCPs in other sessions.

There have been well over a dozen #docday° events now. There has been conversation after conversation after conversation about how to better include people with diabetes in these sorts of events in a meaningful way. There has been community working together to make it happen. And here we are.

For the record, the room was full to overflowing. And the vast majority of the people there were not people with diabetes. Healthcare professionals and researchers made the conscious decision to walk into Hall 118 at 3pm on Wednesday 27 April to hear from the diabetes community; to learn from the diabetes community.

If you missed it, here it is! The other amazing thing about this Symposium was that, unlike all other sessions, it wasn’t only open to people who had registered for ATTD. It was live streamed across #dedoc° socials and is available now for anyone to watch on demand. So, watch now! It was such an honour to be asked to moderate this session and to be able to present the three incredibly speakers from the diabetes community. Right where they – where we – belong.

DISCLOSURE

My flights and accommodation have been covered by #dedoc°, where I have been an advisor for a number of years, and am now working with them as Head of Advocacy.

Thanks to ATTD for providing me with a press pass to attend the conference.

I frequently say that these days, I do hardly anything when it comes to diabetes. I credit the technology behind LOOP for making the last four-and-a-half years of diabetes a lot less labour intensive and emotionally draining than the nineteen-and-a-half years that came before.

It’s true. Justin Walker’s assessment that his DIYAPS has given him back an hour a day rings true. (He said that in a presentation at Diabetes Mine’s DData back in 2018.)

The risk that comes with speaking about the benefits of amazing newer tech or drugs is that we, unintentionally, start to minimise what we still must do. I think in our eagerness to talk about how much better things are – and they often are markedly better – we lose the thread of the work we still put in. But our personal stories are just that, and we should speak about our experiences and the direct effect tech has in a way that feels authentic and true to us.

And that’s why accuracy in reporting beyond those personal accounts is important. Critical even.

Yesterday, the inimitable Jacq Allen (if you are not following her on Twitter, please start now), tweeted a fabulous thread about the importance of getting terminology right when reporting diabetes tech.

She was referring to a tweet sharing a BBC news article which repeatedly labelled a hybrid-closed loop system as an ‘artificial pancreas’. Jacq eloquently pointed out that the label was incorrect, and that even with this technology, the wearer still is required to put in a significant amount of work. She said: ‘…Calling it an ‘artificial pancreas’ makes it sound like a cure, like a plug and play, it makes diabetes sound easy, and while this makes diabetes less dangerous for me, adopting a term that makes it sound like it can magically emulate a WHOLE ORGAN is disingenuous and minimises the amount of time and effort it still takes to keep yourself well and safe.’

Jacq’s right. And after reading her thread, I started to think about the time and effort I had dedicated to diabetes over the previous week.

This weekend, I spent time dealing with all the different components of Loop. For some reason my Dexcom was being a shit and all of a sudden decided to throw out the ‘signal loss’ alert. After doing all the trouble shooting things, I ended up deleting the app and reinstalling it, which necessitated having to pair the transmitter with the app. This happened twice. I also decided it would be a good time to recharge my Fenix (Dexcom G5 transmitter) and reset it.

I ran out of insulin while at a family lunch, necessitating some pretty nifty calculations about how much IOB was floating around, and what that meant in terms of what I could eat from the table laden with an incredible spread of Italian food.

Saturday night, Aaron surprised me with tickets to the Melbourne Theatre Company and in our usual shambolic fashion, we were running late, which meant a little jog (don’t laugh) from the car park to the theatre. I was in high-heeled boots and a skirt that scraped the ground. The degree of difficulty WITHOUT diabetes was high. As I less-than-daintily plunked myself in my seat, I looked at my CGM trace, trying to decide if the 5.5mmol/l with a straight arrow was perfect or perilous, and did a bit of advanced calculus to work out if the audience would be serenaded by the Dexcom alarm at some point in during the 90-minute performance. I snuck in a couple of fruit pastilles under my mask, and surreptitiously glanced down at my watch every ten minutes or so to see if further action was needed. It was. Because that straight arrow turned into double arrows up towards the end of the play.

I spent two hours out of my day off last week for a HCP appointment, as well as several hours dispersed throughout the week trying to work out if there would be any way at all that I might be able to access a fourth COVID boosted prior to flying to Barcelona at the end of the month.

And that doesn’t include the time spent on daily calibrations required because I’m still using up G5 sensors, the pump lines that need replacing every three days (and checked on other days), reservoirs that need refilling (when I remember…) and batteries that need replacing. Or the time set allocated to daily games of ‘Where is my Orange Link’. And the brain power needed to guess calculate carbs in whatever I am eating. (And you bet there are clever people who no longer need to ‘announce’ carbs on the systems they’re using, but the other tasks still have to happen.) It doesn’t include the time out I had to take for a couple of so-called mild hypos that still necessitated time and effort to manage.

Short of a cure, the holy grail for me in diabetes is each and every incremental step we take that means diabetes intrudes less in my life. I will acknowledge with gratitude and amazement and relief at how much less disturbance and interruption there is today, thanks to LOOP, but it would be misleading for me to say that diabetes doesn’t still interfere and take time.

Plus, I’ve not even started to mention the emotional labour involved in living with diabetes. It is constant, it is more intense some days. There are moments of deep and dark despair that terrify me. It is exhausting, and no amount of tech has eliminated it for me.

The risk we face when there is exaggeration about the functionality and cleverness of diabetes tech is that those not directly affected by diabetes start to think that it’s easy. In the same way that insulin is not a cure, diabetes tech is not a panacea. Setting aside the critical issue about access, availability, and affordability, even those of us who are privileged to be able to use what we need, still probably find a significant burden placed on us by diabetes.

This isn’t new. Back in 2015 when Australia was the launch market for Medtronic’s 640G, it was touted as an artificial pancreas, and I wrote about how troubling it was. I stand by what I wrote then:

‘Whilst this technology is a step in the right direction, it is not an artificial pancreas. It is not the holy grail.

Diabetes still needs attention, still needs research, still needs funding, still needs donations. We are not there yet, and any report that even suggests that is, I believe, detrimental to continued efforts looking to further improve diabetes management.

All of us who are communicating in any way about diabetes have a responsibility to be truthful, honest and, as much as possible, devoid of sensationalism.’

It’s why I frequently plead that anyone who refers to CGM or Flash GM as ‘non-invasive’ stops and stops now. There is nothing non-invasive about a sensor being permanently under my skin and being placed there by a large introducer needle. Tech advances may mean we don’t see those needles anymore, and we may even feel them less, but they are still there!

We still need further advancements. We still need research dollars. We still need politicians to fight for policy reform to ensure access is easy and fast and broad. We still need healthcare professionals to understand the failings of technology, so they don’t think that we are failing when we don’t reach arbitrary targets.

We still need the public to understand how serious diabetes is and that even with the cool tech, we need warm hands to help us through. We still need the media to report accurately. And we still need whoever is writing media releases to be honest in their assessments of just what it is they are writing about.

Keep it real. That’s all I am asking. Because overstating diabetes technology understates the efforts of people with diabetes. And that is never, ever a good thing.

What’s the holy grail when it comes to diabetes technology? I suspect the answer may change depending on who you ask. Different people with diabetes, different ideas of burden, different priorities. But one thing that seems to be quite universal is that people with diabetes want to do less when it comes to their diabetes, and they want tech to help with that.

Each and every week, I get asked to review or promote new apps, devices and other types of technology. Or I am asked if I can provide some feedback on an idea which has the aim of improving the life of people with diabetes.

When time permits, I’ll spend some time with developers, and I always start by asking ‘What’s your point of difference?’. I want to know that because there’s so much out there already, and if it’s just another app or program to add to the noise, why bother?

The point of difference I am always searching for is the bit that means doing less. Anything that requires more input or thought process than what is currently available, without offering benefit elsewhere seems to be a waste of time.

I want to do less for more. Surely that’s not asking too much…

For me these days, if I want to check my glucose level, I glance down at my watch. I don’t need to do anything more. Or I swipe right on my iPhone to see a little extra: the header of my Loop app (which shows current glucose level, predicted graph, IOB and battery volume).

To bolus, I either open the Loop app on my phone (two taps after waking my phone), or on my watch and go from there (one tap after waking my watch).

It takes very little effort. I don’t in any way have to stop what I am doing. And it is super inconspicuous. No one knows what I’m doing – not that I’d care. But it’s nice not to have to do something that often draws attention, or questions from others.

I have often wondered if I’ll try a Tandem t:slim pump once Control IQ is finally launched into Australia, and the one thing that is stopping me is knowing that I’d have to give up bolusing from my phone or watch.

New devices or technologies that demand more seem to be in direct contrast to PWD demanding to do less. I wrote this piece after a conference presentation about the (first gen) Medtronic hybrid-closed loop system that showed added burden from users because the system required so much extra input. The very idea that a device developed to increase automation needed users to think about it more was baffling.

DIY systems are developed by people with diabetes, or loved ones of people with diabetes. Having that skin in the game means that there is a determination to deliver not only a product that does more, better, but one that doesn’t add to diabetes burden. You will never hear the idea of ‘it’s good enough’ because to us, it never is!

But even with these goals, there still is a user burden. Cartridges don’t fill themselves; infusion sets don’t change themselves; sensors don’t insert themselves; batteries don’t replace or recharge themselves.

Which brings me to the latest toy I’ve started using, which has managed to cut a few tasks from my diabetes job list.

The diabetes DIY world continues to push the envelope with all components of systems. And the latest from a group that has been looking at the use and affordability of CGM has recently been launched (albeit in limited numbers).

Say hello to Anubis, named for the god of death and the afterlife. The group working on Anubis has worked out how to give used G6 transmitters a new life, and, quite frankly, they are far more impressive in their afterlife! Simon Lewinson from the stunning and aptly named Mt Beauty part of Victoria has led on this work. Simon is the bloke who developed a rechargeable G5 transmitter – the Fenix – which has been one of my all time favourite pieces of DTech ever. I used it continually for about three years, only stopping to trial an Anubis.

I realised just how impressive the other day when I checked the settings on my newly inserted sensor using an Anubis transmitter:

That number circled is when my sensor expires – 60 days after the sensor was inserted. What that means is that there is no need for me to do a restart after 10 days. I’m not sure how many of you reading this have tried to restart a G6 sensor, but my experience has required my husband and a butter knife, and ensuring that sensor restarts were only done when there was harmony in the home. As someone who fully self-funds CGM, I will get every single last minute of life out of a sensor, so restarts G6s up to three times.

The spouse-wielding-cutlery step has now been removed, as has the need for a two hour warm up every ten days. Now, a sensor goes in, and it keeps going until it finally just stops working. I’m not really sure how long that will be. It’s day 12 now and there’s not been a blip, and I’m super interested to know just how many days it will tick along, undisturbed and uninterrupted. I certainly don’t expect to get to 60 days, but I’ll give it a red hot go!

My Anubis is the latest device in my arsenal that is helping to chip away at all the things diabetes demands of me – things that, quite honestly, spark no joy at all. I’ve not yet found that holy grail, but compared with what else there is available to me, and what I have used before, this is better. Less work, less burden, better results. Why wouldn’t I want more of that?!

Want more information?

The Bionic Wookiee has written this terrific piece explaining the nitty gritty tech details of Anubis. My eyes usually glaze over when reading this sort of stuff, but David does a stellar job making it interesting. And understandable!

Want an Anubis? Of course you do. This is the FB page to head to. It’s a new page and there’s not much on there just yet, but it is where info will be shared.

Last week, I posted this on Twitter:

I take no credit for these numbers or that straight CGM line, or the first thing in the morning number that pretty much always begins with a 5. Those numbers happen because my pancreas of choice is way smarter than me. Actually, in a perfect world, my pancreas of choice would not be outsourced, but what are you going to do when the one you’re born with decides to stop performing one of its critical functions?

Anyway. I should know by now that any time diabetes thinks I’m getting a little cocky or too comfortable, something will happen to remind me not to get used to those lovely numbers.

And so, we have Tuesday this week. I woke up with a now very unfamiliar feeling. I reached over and looked at my CGM trace which immediately explained the woolly-mouth-extreme-thirst-desperate-to-pee-oh-my-god-I’m-about-to-throw-up thoughts running through my head. I found the culprit for that feeling very quickly – a pump with an infusion set that had somehow been ripped out overnight.

I didn’t get a screenshot of that number in the high 20s to share, because my head was down the loo. Ketone-induced vomiting is always special first thing in the morning, isn’t it?

I put in a new pump line, bolused and waited, all while resisting the urge to rage bolus the high away. Because that’s all there is to do, isn’t there? I hoped that just waiting and allowing Loop to do its thing would work, and that everything would settle neatly – especially my stomach which was still feeling revolting.

And as I lay there, I had another feeling that is somewhat unfamiliar these days: the feeling that I absolutely loathe diabetes. Beautifully mimicking the waves of nausea were the waves of my total hatred for this condition and how it was making me feel and the way it had completely derailed my morning’s plans.

I don’t feel like that most of the time anymore, because diabetes so rarely halts me from taking a moment out to deal with it. Hypos are so infrequent, and so easily managed; hypers that need real attention just don’t happen; sleep is so seldom interrupted because of diabetes anymore. Life just goes on and diabetes drones on in the background – annoyingly, but not too intrusively.

But this morning was completely handed over to diabetes to wait it out for my glucose levels returned to range – thankfully with a gentle landing and no crash – and for my stomach to stop lurching. Ketones were flushed and the feeling of molasses-y textured blood running through my veins subsided.

By the afternoon I was feeling mostly human, with nothing more than a slight hangover from the morning. But the feeling of diabetes hatred had been reignited and was flashing through my mind constantly.

A couple of days later, with a full day of decent numbers behind me, there is no physical aftermath of those few hours of diabetes trauma. But there is a whisper of the absolute contempt I feel towards diabetes. It’s always there, I guess. It just had reason to rear its ugly head.

The OPEN Diabetes Project is currently running a survey to look at the impact of do-it-yourself artificial pancreas systems (DIYAPS) on the health and wellbeing of users. There are stories all over the DOC about how people with diabetes (and parents of kids with diabetes) have taken the leap to Loop. These stories provide wonderful anecdotal tales of just why and how this tech has helped people.

The idea behind this new survey from the OPEN Diabetes team is to continue to build evidence about the effectiveness of this technology as well as take a look into the future to see just what this tech could have in store.

And important part of this new study is that it is not only OPEN (see what I did there?) to people who are using DIYAPS. That means anyone with diabetes can participate.

This project is important on a number of levels. It was conceived by people with diabetes and a significant number of the people involved in the project team (and I am one of them) are living with diabetes. We very much live the day-to-day life of diabetes and that certainly does make a difference when thinking about research. Also critically important is the fact that the ACBRD has recently joined the OPEN Project consortium. Having a team of researchers exclusively looking at the behavioural impact of diabetes technology will offer insights that have not necessarily been previously considered in such a robust way.

All the information you need can be found by clicking on the image below – including who to speak with if you are looking for more information. Please share the link to the survey with any of your diabetes networks, healthcare professionals who can help pass on details and anyone else who may be able to help spread the word.

A reminder – this is open to everyone with diabetes – not just people using DIYAPS. (I’m stating that again because it may not be all that clear as you are reading through the material once you click through to the survey.) You do not need to be Looping or ever tried the technology. Anyone with any type of diabetes, or parents/carers of kids with diabetes can be involved.

DISCLSOURE

At the best of times, I’ll celebrate any kind of anniversary, but it seemed even more important to acknowledge my ‘loopiversary’ this year in what can really only be termed as the most fucked of times. Last week, I clicked over three years of looping, a decision that remains the smartest and most sensible I have ever made when it comes to my own diabetes management.

In reflecting just how Loop has affected my diabetes over the last three years, I’ve learnt a few things and here are some of them:

- The words I wrote in this post not long after I’d started looping are still true today: ‘…this technology has revolutionised every aspect of my diabetes, from the way I sleep, eat and live. I finish [the year] far less burdened by diabetes than I was at the beginning of the year.’

- The #WeAreNotWaiting community is but one part of the DOC, but it has provided the way forward for a lot of PWD to be able to manage their diabetes in ways we never thought possible.

- Even before I began to Loop, the kindness and generosity of people in that community was clear. I took this photo of Dana and Melissa, two women I am now lucky to count amongst my dearest friends, at an event at ADA, just after they had given me a morale boosting pep talk, promising that not only could I build loop for myself, but they would be there to answer any questions I may have. I bet they’re sorry they made that offer!

- Loop’s benefits are far, far beyond just diabetes. Sure, my diabetes is easier to manage, and any clinical measurement will show how much ‘better’ I am doing , but the fact that diabetes intrudes so much less in my life is, for me, the real advantage of using it.

- That, and sleep!

- I get ridiculously excited when other people make the leap to looping! I have watched friends’ loops turn green for the very first time and have wanted to cry with joy because only now will they understand what I’ve been ranting about. And experience the same benefits I keep bleating on about.

- It’s not for everyone. (But then, no one said it was.)

- You get out what you put in. The more effort and time and analysis you put into any aspect of diabetes will yield results. But with Loop, even minimal effort (I call the way I do loop ‘Loop lite’) means far better diabetes management than I could ever achieve without it.

- It took an out of the box solution to do, and excel at, what every piece of commercial diabetes tech promises to do on the box – and almost always falls short.

- It’s amazing how quickly I adapted to walking around all the time with another but of diabetes tech. My trusty pink RL has just been added to the phone/pump/keys/ wallet (and, of course, mask) checklist that runs through my head before I leave the house.

- Travelling with an external pancreas (even one with extra bits) is no big deal.

- I was by no means an early adopter of DIY tech, but I was way ahead pretty much any HCPs (except, of course, those living with diabetes). The first talk I gave about Loop still scars me. But it is pleasing to see that HCPs are becoming much more aware and accepting of the tech, and willing to support PWD who make the choice to use it.

- The lack of understanding about just what this tech does is astonishing. I surprised to still see people claiming that it is dangerous because users are ‘hacking’ devices. Language matters and you bet that this sort of terminology makes us sound like cowboys rather than having been thoughtful and considered before going down the DIY path.

- The lengths detractors (usually HCPs and industry) will go to when trying to discredit DIYAPS shouldn’t, but does, surprise me. The repeated claims that it is not safe and that people using the tech (for themselves or their kids) are being reckless still get my shackles up.

- Perhaps worst of all are those that claim to be on the side of those using tech, but under the guise of playing ‘devil’s advocate’ do more damage than those who outwardly refuse to support the use of the technology.

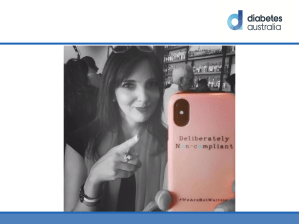

- The irony of being considered deliberately non-compliant when my diabetes is the most compliant it ever has been hurts my pea-sized brain. regularly.

- There is data out there showing the benefits and safety of looping. Hours and hours and hours of it.

- My privilege is on show each and every single time I look at the Loop app on my phone. I am aware every day that the benefits of this sort of technology are not available to most people and that is simply not good enough.

- Despite all the positives, diabetes is still there. And that means that diabetes burnout is still real. But now, I feel guilty when feeling burnt out because honestly, what do I have to complain about?

But perhaps the most startling thing I learnt on this: The most variable – and dangerous – aspect of my diabetes management has always been … me! Loop takes away a lot of what I need to do – and a lot of the mistakes I could, and frequently did, make. Loop for me is safer and so, so much smarter and better at diabetes than I could ever hope to be. I suspect that as better commercial hybrid closed loop systems come onto the market, those who have been wary to try a DIY solution will understand why some people chose to not wait.

And finally, perfect numbers are never going to happen with diabetes. But that’s not the goal, really is it? For me, it’s about diabetes demanding and being given as little physical and emotional time and space in my life. With Loop, sure numbers are better – but not perfect – and I do a lot less to make them that way. It took a system that did more for me, keeps me in range for most of my day, and has reduced the daily impact of diabetes in my life to truly understand that numbers don’t matter.

These days, I usually don’t show my glucose data online. When I first started Looping (about two and a half years ago), I regularly posted the flat CGM lines that amazed and surprised me. I also shared the not-flat lines that showed how hard my Loop app was working as temp basal rates changed almost every five minutes. The technology worked hard so I didn’t need to, and the results were astonishing to me. I shared them with disbelief. (And gratitude.)

I stopped doing that for a number of reasons. It did get boring, and I definitely recognise my privilege when I say that. I also acknowledge my privilege at being able to access the devices required for the technology to work. And there was the consideration that sharing these sorts of stats and data online inevitably lead to comparisons and competition. That was never my intention, but I certainly didn’t want to add to someone having a crappy diabetes day while I blabbed about how easy my day had been.

But today, I’m sharing this:

This was my previous 30-day time in range data from the Dexcom Clarity app on the day I arrived back home in Australia after returning from New York. (My range is set to 3.9mmol/l – 8.1mmol/l.) I’m not sharing it to show off or to boast. I don’t want congratulations or high fives. In fact, if anyone was to see this and pat me on the back, I would respond with the words: ‘I had very little do with it’.

I can’t really take credit for these numbers and would feel a fraud if anyone thought I worked hard to make this happen. Using an automated insulin delivery system full time means that I do so much less diabetes than ever before while yielding time-in-range data that I could once only dream of.

I want to share it, not to focus on the numbers (because it’s NEVER about the numbers!), but to explain what happens when diabetes tools get better and better, and what that means in reality to me.

Those thirty days included the following: End of year break up parties for work and other projects (four of those); ‘We-must-catch-up-before-the-end-of-the-year’ drinks with friends (dozens of those!); actual Xmas family celebrations (three of those over a day and a half– and I’m from an Italian family, so just think of the quantities of food consumed there). Oh, and then there were the three weeks away in NY with my family. Our holiday consisted of long-haul flights from Australia, frightful jet lag (there and back), a lot of food and drink indulgences, out-of-whack schedules, late nights, gallons of coffee, no routine, and more doughnuts than I should admit to consuming.

Add to that some diabetes bloopers of epic proportion that had the potential to completely and utterly railroad any best laid plans: insulin going bad, blocked infusion sets, sensors not lasting the distance, a Dex transmitter disaster.

And yet, despite all of that, my diabetes remained firmly in the background, chugging away, bothering me very little, with the end result being time in range of over eighty per cent.

This graph is only part of the story of why I so appreciate the technology that allowed me to have a carefree and relaxed month. Diabetes intruded so little into our holiday. I bolused from my iPhone or Apple watch, so diabetes devices were rarely even seen. Alarms were few and far between and easily silenced. I was rugged up in the NY cold, so no one even commented on the Dex on my upper arm. The few times I went low, a slug of juice or a few fruit pastilles were all it took, rather than needing to sit out for minutes or hours. Diabetes didn’t make me feel tired or overwhelmed, and my family didn’t need to adapt and adjust to accommodate it.

That time-in-range graph may be the physical evidence that can point to just how my diabetes behaved, but there is a lot more to it, namely, the lack of diabetes I needed to do!

As I spoke about this with Aaron, he reminded me of my well-worn comments about not waiting around for a diabetes cure. ‘You’ve always said that although you would love a cure, it’s the idea that diabetes is easier to manage that excites you. Ten years ago, when you spoke about what that looked like, you used to talk about diabetes intruding less and being less of a burden to your day. That is what you have now. And it is incredible.’

Two years ago, I walked off the stage at the inaugural ADATS event feeling very shaken. I’m an experienced speaker, and regularly have presented topics that make the audience feel a little uncomfortable. I challenge the status quo and ask people to not accept the idea that something must be right just because ‘that’s how it’s always been done’. Pushing the envelope is something that I am more than happy to do.

But after that very brief talk I gave back in 2017, a mere three months after I started Looping, I swore I would never speak in front of a healthcare professional audience again.

That lasted all of about two months.

In hindsight, I was more than a little naïve at how my enthusiasm about user-led technologies would be received. I can still remember the look of outright horror on the face of one endo when I cheerfully confirmed:‘Yes! Any PWD can access the open source information about how to build their very own system. And isn’t that brilliant?!

Fast forward to last Friday, and what a different two years makes! The level of discomfort was far less, partly because more than just a couple of people in the room knew about DIYAPS. In the intervening years, there have been more talks, interviews and articles about this tech, and I suspect that a number of HCPs now have actually met real-life-walking-talking loopers. Plus, Diabetes Australia launched a position statement over a year ago, which I know has helped shape discussions between HCPs and PWDs.

I’ve gotten smarter too. I have rejigged the words I use, because apparently, #LanguageMatters (who knew?!), and the word ‘hack’ scares the shit out of people, so I don’t use it anymore. (Plus, it’s not really accurate.) And, to protect myself, I’ve added a disclaimer at the beginning of my talk – a slide to reinforce the sentiment that I always express when giving a talk about my own life with diabetes, accentuating that I am speaking about my own personal experiences only and that I don’t in any way, shape or form recommend this for anyone else. (And neither does my employer!)

I framed my talk this time – which had the fabulously alliterative title ‘Benefits, Barriers and Burdens of Diabetes Tech’ by explaining how I had wanted to provide more than just my own perspective of the ‘three B’s’. I am but one voice, so I’d crowd sourced on SoMe for some ideas to accompany my own. Here’s just some of the responses.

(Click to enlarge)

(Click to enlarge)And this:

One of the recurring themes was people’s frustrations at having to wade through the options, keep up with the tech and customise (as much as possible) systems to work. And that is different for all of us. One person’s burden is another person’s benefit. For every person who reported information overload, another celebrated the data.

What’s just right for me is not going to be just right for the next person with diabetes. So, I used this slide:

I felt that the story of Goldilocks and the Three Bears was actually a really great analogy for diabetes tech. Unfortunately, my locks are anything but golden, so I needed a little (basic and pathetic) Photoshop help with that.

In this fairy tale, Goldilocks is presented with things that are meant to help her: porridge for her hunger, a seat to relieve her aching legs and then a bed to rest her head after her busy day. But she has to work through options, dealing with things that are not what she wants, until she finds the one that is just right.

Welcome to diabetes technology.

On top of working out what is just right for us, we have to contend with promises on the box that are rarely what is delivered to us. Hence, this slide:

Apart from the Dex add circled in red, all the other offerings are ‘perfect’ numbers, smack bang in the middle of that 4-8 target that we are urged to stay between. These perfect numbers, obviously belonging to perfect PWD with their perfect BGLs, were always completely alien to me.

A selection of my own glucose levels showed my reality.

I explained that in my search for finding what was ‘just right’, I had to actually look outside the box. In fact, for me to get those numbers promised on the box, I had to build something that didn’t come in one. (Hashtag: irony)

Welcome to Loop! And my next slide.

And that brings us back to two years ago and the first time I spoke about my Looping experience in front of healthcare professionals. It was after that talk, during a debrief with some of my favourite people, that this term was coined:

Funny thing is, that I am now actually the very definition of a ‘compliant’ PWD. I attend all my medical visits; I have an in-range A1c with hardly any hypos; I am not burnt out. And I have adopted a Goldilocks approach in the way I do diabetes: not too much (lest I be called obsessive) and not too little (lest I be called disengaged), but just right.

It turns out that for me to meet all those expectations placed on us by guidelines and our HCPs, I had to do it by moving right away from the things there meant to help us. The best thing I ever did was start Loop. And I will continue to wear my deliberate non-compliance as a badge of honour and explain how it is absolutely just right for me!