You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Guest post’ category.

Have you see The Human trial, the documentary film about searching for a cure for type 1 diabetes? I saw it a while ago, and then again last week. It’s remarkable viewing.

I’m delighted to publish this guest post from Elizabeth Snouffer, freelance writer, diabetes advocate and a remarkable woman I’m fortunate to call a friend. Elizabeth wrote this review of The Human Trail just after it was released to US audiences, but I wanted to wait to share it until it could be viewed by people from around the world. Thanks, Elizabeth, for sharing your thoughts.

___________________________________________

The Human Trial documentary film is an intimate look at the overwhelming, messy, and unpredictable nature of living with type 1 diabetes alongside a similarly defined clinical trial seeking to fund and find a cure for the disease. Directors, Lisa Hepner and Guy Mossman, have painstakingly worked on their documentary film for more than a decade as Producer and Writer, and Director of Photography respectively. Abramorama released the film in theaters on June 24, 2022.

Diagnosed with type 1 diabetes at age 21, Hepner, who narrates the film, represents millions of people in the diabetes community – including families, physicians, advocates and more – who would do anything to put an end to the auto-immune condition that leads to terrible complications and early mortality.

Mossman calls his documentary an observational film and it is hard to disagree. The cinéma vérité approach allows the audience to experience the relentless burden diabetes exacts on the people it touches. In the first scene, we watch Hepner prick her finger for blood while her 3-year-old son Jack looks after the test strip in the glucose meter. He is excited but turns quiet while we observe the countdown and Jack tells his mom the result—2-9-4. Hepner brushes off her disappointment and Jack quickly moves on asking Dad to test his glucose. Mossman complies with the child’s request, but the result, 96 mg/dL is startling. The health gap between Jack’s parents is a poignant reminder of the difficult impact disease has on a family. “I’ve spent the last 30 years trying to outrun diabetes, but it’s not working,” says Hepner as she prepares for an appointment with her nurse practitioner, expressing hope to stave off retinopathy and blindness. Without adequate care for blood glucose stability, what will tomorrow bring for this young family? When the well-meaning public questions prioritizing a diabetes cure because insulin is often misrepresented as the answer, The Human Trial offers a strong rationale for funding diabetes cure research.

The film is always on the move, symbolic of the stamina it takes to both manage a chronic illness and fight for cures. From her car, Hepner asks “Why is the cure for diabetes taking so long?” and we wonder, too. Viacyte, a California Bio-tech company, gives Hepner and Mossman real-time access to film various aspects of their first clinical trial – only the sixth-ever embryonic stem cell trial in the world. It’s clear the film has moved away from the personal sphere into medical science and in a sense, the business of diabetes. We become onlookers to an employee filled conference room celebration and listen to former Viacyte CEO, Paul Laikind, announce FDA approval for the biotech’s first human clinical trial with a bio-artificial pancreas. We feel the impact of their excitement and anxiety. Will our methods work? Will we run out of money?

Trials take place across the world but Hepner and Mossman’s camera lands at the University of Minnesota where the first participants, who are high risk for acute life-threatening complications, are implanted with multiple small-format cell-filled devices called sentinels to evaluate safety and viability. Maren, aka Patient 1, suffers from hypoglycemic unawareness and seizures, and Gregory, Patient 2, is concerned about vision loss. Their ability to deal with adversity is uncanny, and their fortitude as pioneers on a surgical journey to the unknown is inspiring to watch. We observe the operating room from above as Maren and Gregory are implanted and witness the risks associated with the new therapeutic approach. They have similar questions to the Viacyte team, but the stakes are higher.

Could I be cured?

Participants in clinical trials aren’t usually given any indication of outcomes before trial completion which is understandably excruciating for Maren and Gregory during the trial. The countless surgeries and tests are grueling, and we are gripped by their resilience on the screen and our mutual desire for a positive outcome.

The Human Trial gives visibility to the invisible—the often-hidden and challenged lives of people with type 1 diabetes and the thousands of scientists and researchers working arduously to fund and discover cures. The film’s subjects are not just fighters; they have accepted how obstacles, even failures, are a part of the journey to success. I call that courage.

Please click here to see where you can watch.

Elizabeth Snouffer is a freelance writer living in New York City.

Edwin Pascoe, who works as a registered nurse and credentialled diabetes educator, has explored the uniqueness of sexual orientation (gay) among men with type 2 diabetes in his PhD thesis with Victoria University.

This is Edwin’s second post for Diabetogenic (read the first one here).

This weekend, the Mid-summa Pride March marks its 25th year of the LGBTQIA+ community and this year diabetes will be represented. Edwin invites you to participate and march in what appears to be the first-time diabetes has been represented at such an event in the world.

To get involved in this historic event and support LGBTQIA+ people with diabetes, please contact Edwin Pascoe on diabetes-education@hotmail.com.

But first, read Edwin’s post.

They say that you can’t really know what it’s like to experience a particular-group of people’s world, unless you have been there yourself. The reason is that your vantage point restricts your line of sight. You only get to see certain things and while people can explain these things to you, their gravity may remain elusive.

This line of sight is often further obscured by well-meaning comments directed at members of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Asexual, Intersex plus (LGBTQIA+)

community, such as ‘aren’t we all the same’, which are often offered up when a person makes that leap of faith to come out as non-heterosexual to their health care practitioner.

In a sense LGBTQIA+ people are shut down in these conversations by such comments and blended into some kind of homogenised one size fits all approach: a far cry from patient centred care. To put it crudely, it’s nice not to stick out like dogs’ balls but there are times when its important, and even pivotal to explain your truth when speaking about matters as important as your health.

However, the influences among LGBTQIA+ people are so subtle and varied that they escape detection, by even the people who are affected by them – these are often described as incognizant social influences.

For many, the idea of sexual orientation having an influence on diabetes management does not make sense, so when this idea is challenged cognitive dissonance comes into play.

Cognitive dissonance is an internal psychological self-talk that serve to maintain some sort of order when beliefs are inconsistent. Internal beliefs shared by many HCPs are:

- They treat all patients equally

- Being gay (sexual orientation) is about sex practices, hence the word sexual orientation.

- Psychosocial factors influence people’s management of diabetes and so need to be considered in diabetes education.

However, these 3 factors clash and have, to this date, resulted in silence when it comes to talking about sexual orientation and diabetes as evidenced by a lack of research in the diabetes space within Australia and indeed the world. Silence, however, only serves to further perpetuate this silence.

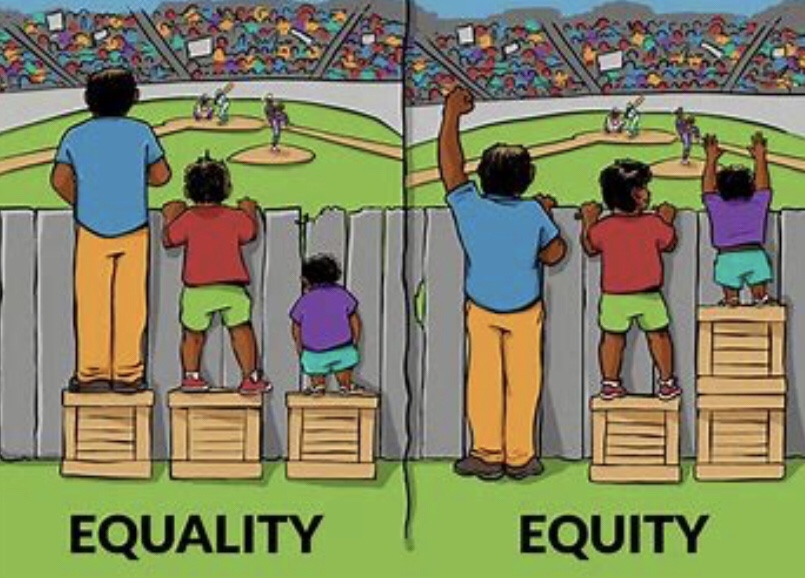

While point 3 is true, point 1 and 2 may not be the case. In point 1, many people in my study expressed that they treat all people the same which is probably true, but does that mean the people they care for receive equitable care or equal chance of access? Review this famous picture which makes it abundantly clear that we must do different things to achieve the same outcome.

There are myriad psychosocial factors that are unique to LGBTQIA+ people with diabetes, e.g. homophobia in sport, eating disorders such as binge eating disorder found to be at higher rates in gay men and stress (including depression and anxiety) and stress related behaviour (smoking, drugs e.g. amyl nitrate effecting eye health, alcohol).

Likewise support structures among gay men are generally quite different. For straight people their family will often be there to support them when required (e.g. taking them to an appointment, motivating them to take medicines and monitor or seek help and assisting them in an emergency.) For LGBTQAI+ seeking support can be problematic as they may be estranged from their family to varying degrees; provision by religious groups are absent for many gay men; and they may disengage from the gay community if they don’t meet image ideals that can exist.

Loneliness and isolation is a problem in the LGBTQIA+ community. In point 2, the belief that the discussion of ‘gay’ is synonymous with a discussion of sex, is quite pervasive but only represents one aspect of a person’s life. This obsession with sex of gay men has been represented in a multiplicity of discourses, from different powerful institutions in society throughout history like law, religion and medicine, that have directed that conversation, including endocrinology.

A German doctor by the name of Eugen Steinach in the speciality of endocrinology performed orchidectomies on gay males in the 1920s and transplanted them with those of straight males, in the belief that homosexual tendencies were rooted in the testicles. Various barbaric gay conversion practices were carried out up until recently; while time-lines are unclear due to wide spread secrecy, we know homosexuality was removed as a mental illness in 1992 in the WHO ICD classification system.

However, 28 years on, the legacy effect of this cruel regime remains ever present in medicine as reported by various Australian studies and case reports of homophobia. There is a paucity of education within healthcare on matters of LGBQIA+ people and this is in part leading to ongoing ignorance.

In addition to this specialisation within medicine has meant that those who are well informed on LGBTQIA+ issues are usually far removed from mainstream medicine e.g. sexual health and mental health clinics, meaning possibilities for mentoring by colleagues and upskilling is reduced.

Again, LGBTQIA+ remain invisible as we don’t tend to record this information due to sensitivities around this topic. Generally, we use labels to denote difference but leave them out if they are part of the ‘norm’. This is problematic as the so-called norm is that which other things are compared to, while those labelled are counted as second to the norm – but at least they are counted. However even more frightful are those that don’t receive the reward of that label – they are the invisible.

To put it in religious terms we could refer to this last group as the dammed. Therefore, it is those of the ‘norm’ that get to decide who gets counted and who do not. For example, we talk about women in cricket, why? to denote they exist and are unique as compared to the norm which are men. However, what would it mean if we didn’t label women in cricket? Would it render them invisible and we didn’t get to see their contribution? We don’t say men in cricket.

It is common to talk about men in nursing to denote they bring a difference to nursing, normally a female dominated profession. Of course, these labels are artificial but speak to power of words in healthcare and why LANGUAGE MATTERS.

Sexual orientation labels are however judiciously applied in medicine as there is a lot of anxiety around this. Anxiety arises from HCP who fear causing offence and LGBQIA+ people themselves who fear discrimination by HCP. Anxiety is often attributed to the sexual factors and as such attempt to adjust this medical gaze must be challenged and adjusted to above the waist to encapsulate the entire person because maybe only then, the laser sharp focus on sex and the judgment that goes with this may start to dissipate? It doesn’t mean we forget sex but that this only becomes part of the whole. This is important, as both the sexual practices and the non-sexual practices of people contribute to health in diabetes.

Sexual health education in diabetes for all people e.g. male, female, LGBTQIA+ and HIV is presently only rudimentary and for some non-existent. Our sensitivities in this are harming people with diabetes.

Straight people are spared the need to come out with a label as this is the norm. They have the freedom to flow casually into and out of conversations which encapsulate topics such as relationships and sex, which gay men must first censor or even disguise if it means coming out, if they want an answer to their question.

While the topics such as erectile dysfunction may be similar between gay and straight men, the psychosocial context of these are different which HCP must be attuned to if they are to develop a therapeutic relationship, but are they? While it is clear that there are some homophobic HCPs out there, for the most it’s a lack of awareness and nervousness about how to navigate this field.

Although it’s unclear why, in my study, gay men with type 2 diabetes attended allied health services 50% less than the general population in Australia e.g. diabetes educators, dieticians and endocrinologist. In addition to this those who didn’t attend, displayed an increase in complications and a trend towards glucose levels outside the range. This highlights 2 things here, one is that multidisciplinary care works and secondly that gay men disengage from these services that can help. Allied health needs to explore ways to better engage LGBTQIA+ people through education and further research.

As National Diabetes Week activities began, I kept a close eye on the Twittersphere to see just how the week was being received. Pleasingly, there were a lot of mentions of the #ItsAboutTime campaign, and I set about retweeting and sharing activities by others involved in the week.

One tweet, from Edwin Pascoe, caught my attention:

Edwin Pascoe is a registered nurse and credentialled diabetes educator in Victoria. He is currently undertaking a qualitative study as part of a PhD at Victoria University into the lives of gay men and type 2 diabetes in the Australian context. Data is collected but analysis is underway.

I read Edwin’s tweet a few times and realised that he is absolutely right. I can’t think of ever seeing anything to do with any diabetes campaign that addresses the specific issues faced by LGBTI people with diabetes. So, I reached out to Edwin and asked if he would like to write something for Diabetogenic. I’m so pleased he did.

One of the criticisms of diabetes representation in the media is that it lacks diversity. I completely agree with that sentiment. Because while we certainly may share stories, we also need more voices and more perspectives, and come to understand that there are different, unique and varied experiences and issues faced by different groups.

I’m thrilled to feature Edwin’s post today, and am so grateful that he took the time to write it.

__________________________________________________

CDE, Edwin Pascoe

Diabetes is a chronic condition that is managed in the context of people’s lives and this fact has been increasingly recognised by peak bodies in diabetes within Australia such as Diabetes Australia, Australian Diabetes Society, Endocrinology Society of Australia and The Australian Diabetes Educators Association.

Diabetes education has therefore become not just about defining diabetes and treatment for people but exploring how people with diabetes manage these things in context. Creating the freedom and space for people to speak their truth will allow health practitioners to explore appropriate solutions that are congruent with the person with diabetes needs.

The following will cover some of this context and how sexual orientation may influence diabetes.

Context is everything

The context of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) persons has not been recognised formally by these same peak bodies in diabetes specifically. Arguments shared informally have suggested that what people do in bed does not affect diabetes and considering we have full equality under the law why would it matter. Further to this health care professionals (HCPs) have suggested none of this worries them as all people are treated the same, but herein lies the problem as:

- Not all people are the same.

- LGBTI people are still not fully recognised under the law in Australia despite the recent success in Marriage Equality. For example religious health care services and schools are permitted under law to fire or expel anyone that does not follow their doctrines. In some states gay conversion (reparative therapy) is still legal despite the practice having been shown to cause significant psychological harm. It is also important to note that it was only quite recently that the last state Tasmania decriminalised homosexuality in 1997 so this is in living memory.

- The law is not the only determinant of social acceptability but is entrenched in culture (we know this from numerous surveys that have seen the up to 30% believe that homosexuality as immoral (Roy Morgan Research Ltd, 2016)). Law changes have only meant that in part hostilities have gone underground.

- The focus on sex or what people do in bed fails to see people as whole and often lead to false claims of promiscuity in LGBTI people. There are also assumptions in relation to what people do in bed for example anal sex is one of these stigmatised practices. In reality not all gay men practice this and a significant percentage of heterosexual people do engage in anal sex.

Reports from the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention in the USA identified that 44% heterosexual men and 36% of heterosexual women have engaged in anal sex (Chandra, 2011). Mild displays of affection such as holding hands and leaning into each other engaged routinely by heterosexual couples are heavily criticized when observed in same sex attracted people causing LGBTI people to self-monitor their behaviour. If they choose to engage in this behaviour it is often considered and calculated rather than conducted freely.

The result of this is that there is a lot of awkwardness around the topic of sexual orientation for both the HCP and LGBTI person, something not talked about in polite company. This means that rather than talking about their health condition in context there is tendency to talk in general terms if they are recognised as LGBTI, or they are assumed heterosexual until the person outs themselves during the consultation.

However outing oneself can be an extremely stressful experience as, despite good intentions by HPCs, LGBTI people may still be fearful and remain silent to the point of even creating a false context (a white lie to keep themselves safe). It has been a known practice among some LGBTI people that some engage in the practice of ‘straightening up’ the house if they know HPCs or biological family members are coming to their homes, to again keep themselves safe. This is not to say that all situations are this bleak but that for some at least it is. Does this prevent people from seeking help in the first place when required?

Studies on rates

In the USA Nurses’ Health Study, it was noted that the rates of diabetes in lesbian and bisexual women was 27% higher (Corliss et al., 2018). Anderson et al. (2015)examined electronic records for 9,948 people from hospitals, clinics and doctors’ offices in all 50 states (USA). Data collected included vital signs, prescription medications and reported ailments, categorised according to the International Classification of Diseases diagnostic codes (ICDs). They found that having any diagnosis of sexual and gender identity disorders increased the risk for type 2 diabetes by roughly 130 percent which carried the same risk as hypertension. Wallace, Cochran, Durazo, and Ford (2011), Beach, Elasy, and Gonzales (2018)also looked at sexual orientation in the USA and found similar results.

However one must consider the country in which this data was collected as acceptability of diverse sexualities and differences in health care systems do make a difference. In a study within Britain the risk for type 2 diabetes was found to be lower than the national level (Guasp, 2013). In Australia the rates of diabetes in a national survey came out as 3.9% in gay men in 2011 (Leonard et al., 2012)and this was the same as data collected by Australian Bureau of Statistics (2013)for that year (they did not differentiate between types).

Life style factors

Life style factors such as exercise and food consumption are important to consider as these are tools used to manage diabetes. Studies have found significant level of homophobia in Australian sport that prevents participation(Erik Denison, 2015; Gough, 2007)and that there are elevated levels of eating disorders including binge eating disorder in LGBTI people (Cohn, Murray, Walen, & Wooldridge, 2016; Feldman & Meyer, 2007).

Qualitatively, a study was conducted in the UK/USA by Jowett, Peel, and Shaw (2012)exploring sex and diabetes, and in this study one theme noted was that equipment such as an insulin pumps put participants in a position to have to explain and the fear they were being accused of having HIV.

Stories

The following two stories may help give context to how sexual orientation has influenced these two people’s lives.

The first story is regarding a gentleman who came to see me for diabetes education for the first time who had lived the majority of his life hiding his sexual orientation due to it being illegal. During the consultation I was trying to explore ways to increase his activity levels in order to improve blood glucose levels, strength and mental health. He advised he didn’t like going for walks even if it was during the day in a built-up area as it was dangerous. When asked to explain this he said he feared being attacked due to his sexuality as he felt he looked obviously gay, but I didn’t see that.

A second story later on was from an elderly lesbian woman who was showing me her blood glucose levels. I noted her levels were higher on Mother’s Day, so I obviously asked what was going on there. She bought out a picture of her granddaughter from her purse which immediately bought a tear to her eye. She said her daughter had a problem with her sexual orientation and so stopped her from seeing her granddaughter, and that it had been two years since she had seen her.

It’s only the start

It is important to note that each letter of the LGBTI acronym has their own unique issues with regard to diabetes. I have mainly talked about gay men here as this is what my study covers but there are studies on transgender people (P. Kapsner, 2017), increased rates of diabetes in people with HIV (Hove-Skovsgaard et al., 2017)and of course many others. In Australia we don’t routinely record sexual orientation, only in areas of mental health and sexually transmitted diseases, and as such data is lacking in this area. It’s time to be counted and there is a need to learn new ways to improve engagement for LGBTI people with diabetes.

References

Anderson, A. E., Kerr, W. T., Thames, A., Li, T., Xiao, J., & Cohen, M. S. (2015). Electronic health record phenotyping improves detection and screening of type 2 diabetes in the general United States population: A cross-sectional, unselected, retrospective study.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2013). Australian Health Survey: Updated Results, 2011-12. from http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by%20Subject/4338.0~2011-13~Main%20Features~Diabetes~10004

Beach, L. B., Elasy, T. A., & Gonzales, G. (2018). Prevalence of Self-Reported Diabetes by Sexual Orientation: Results from the 2014 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. LGBT Health, 5(2), 121-130. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2017.0091

Chandra, A. (2011). Sexual behavior, sexual attraction, and sexual identity in the United States [electronic resource] : data from the 2006-2008 National Survey of Family Growth / by Anjani Chandra … [et al.]: [Hyattsville, Md.] : U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, [2011].

Cohn, L., Murray, S. B., Walen, A., & Wooldridge, T. (2016). Including the excluded: Males and gender minorities in eating disorder prevention. Eating Disorders, 24(1), 114-120. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2015.1118958

Corliss, H., VanKim, N., Jun, H., Austin, S., Hong, B., Wang, M., & Hu, F. (2018). Risk of Type 2 Diabetes Among Lesbian, Bisexual, and Heterosexual Women: Findings From the Nurses’ Health Study II. Diabetes care, 41(7). doi: https://doi.org/10.2337/dc17-2656

Erik Denison, A. K. (2015). Out on the fields.

Feldman, M. B., & Meyer, I. H. (2007). Eating disorders in diverse lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 40(3), 218-226. doi: 10.1002/eat.20360

Gough, B. (2007). Coming Out in the Heterosexist World of Sport: A Qualitative Analysis of Web Postings by Gay Athletes. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Psychotherapy, 11(1/2), 153.

Guasp, A. (2013). 2013Gay and Bisexual Men’s Health Survey. Retrieved 09/07/2018, 2018, from https://www.stonewall.org.uk/sites/default/files/Gay_and_Bisexual_Men_s_Health_Survey__2013_.pdf

Hove-Skovsgaard, M., Gaardbo, J. C., Kolte, L., Winding, K., Seljeflot, I., Svardal, A., . . . Nielsen, S. D. (2017). HIV-infected persons with type 2 diabetes show evidence of endothelial dysfunction and increased inflammation. BMC Infectious Diseases, 17(1), 234-234. doi: 10.1186/s12879-017-2334-8

Jowett, A., Peel, E., & Shaw, R. L. (2012). Sex and diabetes: A thematic analysis of gay and bisexual men’s accounts. Journal of Health Psychology, 17(3), 409-418. doi: 10.1177/1359105311412838

Leonard, W., Pitts, M., Mitchell, A., Lyons, A., Smith, A., Patel, S., . . . Barrett, A. (2012). Private Lives 2: The second national survey of the health and wellbeing of gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender (GLBT) Australians.

- Kapsner, S. B., J. Conklin, N. Sharon, L. Colip; . (2017). Care of transgender patients with diabetes. Paper presented at the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, Lisbon Portugal http://www.abstractsonline.com/pp8/#!/4294/presentation/4612

Roy Morgan Research Ltd. (2016). “Homosexuality is immoral,” say almost 3 in 10 Coalition voters [Press release]

Wallace, S. P., Cochran, S. D., Durazo, E. M., & Ford, C. L. (2011). The Health of Aging Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual Adults in California. Policy brief (UCLA Center for Health Policy Research)(0), 1-8.

I get to meet some pretty awesome people with diabetes around the globe. At EASD I caught up with Cathy Van de Moortele who has lived with diabetes for fifteen years. She lives in Belgium and, according to her Instagram feed, spends a lot of time baking and cooking. Her photos of her culinary creations look straight out of a cookbook…She really should write one!

I get to meet some pretty awesome people with diabetes around the globe. At EASD I caught up with Cathy Van de Moortele who has lived with diabetes for fifteen years. She lives in Belgium and, according to her Instagram feed, spends a lot of time baking and cooking. Her photos of her culinary creations look straight out of a cookbook…She really should write one!

Cathy and I were messaging last week and she told me about an awful experience she had when she was in hospital recently. While she wasn’t the target of the unpleasantness, she took it upon herself to stand up to the hospital staff, in the hope that other people would not need to go through the same thing. She has kindly written it out for me to share here. Thanks, Cathy!

______________

‘Good day sir. Unfortunately we were not able to save your toes. There’s no need to worry though. We’ll bring you back into surgery tomorrow and we’ll amputate your foot. It won’t bother you much. We’ll put some sort of prosthetic in your shoe and you’ll barely notice…’

I’m shocked. Still waking up from my own surgery, I’m in the recovery room. Between myself and my neighbour, there’s no more than a curtain on a rail separating us. I feel his pain and anxiety. He is just waking up from a surgery that couldn’t save his toes. This man, who is facing surgery again, leaving him without his foot. How is he gonna get through this day? How will he have to go on?

The nurse besides my bed, is prepping me to go back to my room. I tell him I’m shocked. He doesn’t understand. I ask him if he didn’t hear the conversation? His reaction makes me burst into tears.

‘Oh well, it’s probably one of those type 2 diabetics, who could not care less about taking care of himself.’

I’m angry, disappointed, sad and confounded. I ask him if he knows this person. Does he know his background? Did this man get the education he deserves and does he have a doctor who has the best interest in his patient? Is he being provided with the right medication? Did he have bad luck? Does he, as a nurse, have any idea how hard diabetes is?

The nurse can tell I’m angry. He takes me upstairs in silence. My eyes are wet with tears and I can only feel for this man and for anyone who is facing prejudice day in day out. I’m afraid to face him when we pass his bed. All I can see is the white sheet over his feet. Over his foot, without toes. Over his foot, that will no longer be there tomorrow. I want to wish him all the best, but no words can express how I feel.

What am I supposed to do about this? Not care? Where did respect go? How is this even possible? Why do we accept this as normal? Have we become immune for other people’s misery?

I file a complaint against the policy of this hospital. A meeting is scheduled. They don’t understand how I feel about the lack of respect for this patient. They tell me to shake if off. Am I even sure this patient overheard the conversation? Well, I heard it… it was disrespectful and totally unacceptable.

Medical staff need to get the opportunity to vent, I totally agree. They have a hard job and they face misery and pain on a daily basis. They take care of their patients and do whatever is in their power to assist when needed. They need a way to vent in order to go home and relax. I get that. This was not the right place. It was wrong and it still is wrong. This is NOT OKAY!

Today, I am so pleased to have Jane Reid guest blog for me. I’ve never met Jane in real life (I hope to one day!), but we are friends on Facebook and seem to have very similar interests. We share a lot of posts about books, libraries, grammar and punctuation. Jane often posts really thoughtful and honest comments to my blog posts and I am always so interested to hear her opinion and experiences. Thanks for sharing today, Jane.

I have lived with T1 for 50 years – well, almost, but who’s counting?

It seems like a long time, but it has whizzed by. From diagnosis, (diabetic ketoacidosis and coma), to now, (pump, some hypo unawareness and some complications), I have lived it all with the help of my parents, my friends, my HCPs, and most of all, my husband who has put up with nearly 43 years of type 1. He told me yesterday that any sort of illness or set back that affects one of us is OUR problem. That is true love.

For the first few years I lived through what I call the ‘dark ages’. Glass syringes, horrible, large needles that went blunt quickly and testing (if you can call it that) with tablets dropped into a mixture of urine and water. If the result was blue, you were probably hypo; if the result was orange-brown you were high. My first specialist-physician (did they even have endos in 1965?) did me the greatest favour he could have. He told me that I would be the person who knew most about my diabetes, and he was correct. Thank you, Tom Robertson!

When I look back, I now realise that I had gastroparesis from quite early on, although it was only diagnosed ten years ago. Maybe I just didn’t want to know at that time, and I certainly never told any HCPs. I could probably have saved myself a lot of grief if I had.

The complication I really feared was retinopathy. I am a voracious reader, and I had heard gruesome tales of people going blind. Well, it wasn’t as bad as that, and it took over twenty years to develop. The treatment was worse than the fear, and the waiting around to see the ophthalmologist was worse than the treatment. I was treated by an ophthalmologist whom I can only describe as arrogant, and patronising. He did, however, save the majority of my sight, although I have almost no peripheral vision and can no longer drive.

I have had no treatment for over twenty years, so I guess he knew what he was doing. Losing my driving licence was the worst thing for me, although it was not until ten years ago. It has, to a certain extent, taken away my autonomy and independence, although every time I get into the car I know why I no longer drive. Believe me; everyone else on the road is safer because I’m not behind the wheel!

My latest complication is diabetic nephropathy (CKD). I was, to put it mildly, surprised and depressed when I found out. Luckily, the specialist I was sent to in the ACT, put me at ease, told me all about it, and arranged for a kidney biopsy. That showed that the disease was not nearly as bad as first thought, and was only at the very first stage. His comment to me was ‘I’m the same age as you, and I’ll look after you for the next seven years, and then I’ll hand you onto someone else when I retire’. That was reassuring!

I’d prefer not to have type 1 diabetes, but I can live with it. I’ve found out that I can live with complications; sure, I’d prefer not to, but they just become part of life. The worry and the fear are worse than the reality. I just do the best I can. None of us can do more than that.

Jane Reid is a proud member of the Newcastle Knights Rugby League Club and early next year will be eligible to receive a Kellion Medal for living with type 1 diabetes for 50 years – congratulations Jane!

Last month, my mate Mike Hoskins asked me to write something for Diabetes Mine. So I did.

It’s called A Word From Down Under, and I’m a little annoyed I didn’t add some commentary about throwing shrimps on the barbie, riding my ‘roo to work, or eating vegemite sangas. Missed opportunity.

This is the story of Hypo Boy who, when not being a superhero, is the fabulous Spike Beecroft. I’ve known Spike for quite some time, and his incredibly amusing anecdotes about his life with diabetes never fail to have me in fits of laughter. This is a classic Hypo Boy tale that has been shared many times before. Recently, it appeared again on my Facebook page, and I asked Spike to guest blog and write about it here so you could all enjoy. Take it away, Hypo Boy…

People with diabetes are super human in lots of ways. We do the little bit extra that others just can’t do. Sure it’s not flying or shooting laser beams but it is a little extraordinary, and when you’re in hypo zone, that ‘super-ness’ can overwhelm your brain and give you powers you didn’t know you had; in fact it can give you powers you don’t actually have but you become convinced they’re there. My inner and very confused superhero is Hypo-Boy.

There are a number of things we all have to do in life that are stressful. Some we can manage to avoid with very little effort, like speaking in public or getting married. One stressful occasion that is difficult to avoid is moving house. Even if you opt to stay with your parents for your life at some point they will move to avoid you.

Stress does strange things to PWD and stressful situations confuse your finely-tuned spider sense of what’s going on with your finely-tuned and gym-trained body. If you’re hypo unaware and under massive stress and your gym routine consists of only riding a bike (you’ve seen those guys – they’re all legs and bits of string from their shoulders instead of arms) then moving house is a disaster waiting to happen.

The fateful day had arrived and I’d started the long and very strenuous task of packing up the house into boxes, loading said boxes into the truck and then transporting them to their next destination. Being an engineer and a logical person with type 1, I decided to start working from the back of the house and move forward. It was a clear and concise plan that involved the placement of items in the truck with regard given to weight, size, ease of load and unload. It was a perfect plan.

Then I started moving stuff.

It was going well – I was ahead of my predetermined plan, boxes where moving, I had a rhythm, I didn’t have time to test, I stumbled occasionally due to the weight/size of the stuff I was moving, the sweat on my brow was what they talked about in VB ads. I was THE MAN.

Hypo Boy knows one thing and he knows it well – Hypo boy knows when he’s low and everyone else are retards of the highest order. In retrospect the stumbling was due to being low and not being super co-ordinated; the sweat was from being low. But I was on schedule and I do like the odd VB.

The last item to be moved from the room was a big white couch. It’s a three person couch – one of those things that’s not super heavy, but is awkward to manoeuvre. It’s really a two-person job, but Hypo Boy can convince you (and himself) of many things including that he is THE MAN and that physics and ergonomics are fantasies. And also that the fuzzy vision and misjudging the size of items is just from the stinging of man-sweat.

Hypo Boy decided that the most efficient way to manoeuvre the couch out of the room was to tip it vertically and slide it on one end through the doorway. Lifting couch vertically and sliding couch on the fabric side across floorboards couldn’t be easier. Hypo Boy’s brain knows its stuff. This was going to work. Perfectly! Or until it’s halfway through the door and perfectly jammed in the door jamb.

Whilst a couch on its side does slide nicely across a polished timber floor, a vertically arranged couch with its back facing you, jammed in a doorframe provides almost nothing to grip on and use to push either forwards or to pull back on to reverse the operation.

After a few tries at various methods to move the couch, the sudden and very real feeling of weakness that comes from realising that you’re low hit. , And I realised I was not just low, but orange-box-NOW kind of low. Hypo boy had deserted me; taking with him his strength and mental clarity and leaving me stuck in a room with no hope of escape because I’d successfully stuck a couch in the only exit.

A real feeling of fear as I desperately tried to un-jam the couch and get to the hypo fix. But when you’re really low the ability to open a Mars Bar can escape you let alone trying to move a couch! And logically working out how to move the thing is way beyond what I capable off. It was looking grim. I could see the news headlines –MAN FOUND DEAD TRAPPED IN OWN ROOM. POLICE BAFFLED.

Fortunately for all of Hypo Boy’s fans an alternative plan hatched. Maybe – just maybe – Hypo Boy’s last vestiges of power would help. Exit the room via the window! And so I did. Then the next challenge: the locked back door. Again Hypo Boy’s brilliance came through: crawl through the dog door. Hypo boy looks good in lycra, but could afford to lose a few kilos. Doggie door needed some minor attention after its use by an animal several sizes larger than the designers ever considered.

Finally the kitchen! Hypo boy could save himself!! Why Hypo Boy had packed the jelly beans first was a question for later. There were slightly stale and not so crisp Ginger nut biscuits that would have to do! Well done Hypo Boy. Well done.

Later forensic investigation would reveal that:

a) the couch was pretty well jammed in

b) trying to grab the couch on the other corner would have made the couch twist nicely and popped it out of the door allowing the move to continue, Hypo Boy is obviously VERY, VERY focused on the right side of the world.

Thank you Spike for guest posting today. Please come back again and share more of your stories!