You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Real life’ category.

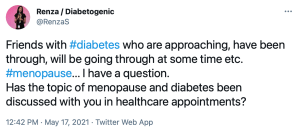

I searched for this blog post the other day after a Zoom catch up with a diabetes friend who mentioned that they were feeling really guilty because diabetes seemed to impact so much on those around her.

It’s hard to not feel that guilt, and when we feel guilty we often apologise. Apologising for diabetes is like apologising for lousy weather on a day we planned a garden party. We didn’t cause the rain. We didn’t cause our diabetes, or the parts of it that interrupt our day and mess up our plans.

I sent this post to my friend and she called me straight away to say that it helped her understand that she doesn’t need to constantly say sorry when diabetes throws a spanner into the works. It’s a hard habit to break. I realised that it was four years ago I resolutely wrote this post, mostly as a reminder to myself. I wish I could say that I’ve managed to nail it and have stopped apologising for diabetes being an inconvenience. But I’d be lying if I suggested I get it right all the time – perhaps I just need a prompt every now and then.

And if anyone else needs a reminder too, here it is for you…

________________________________________________

Recently, I heard myself saying to a friend with diabetes that she really didn’t need to – and shouldn’t – apologise for diabetes, specifically, for needing to stop to check her BGL while we were mid-conversation.

‘Don’t apologise,’ I said to her. ‘It’s just part and parcel of diabetes.’

And then, I heard how often I do it.

‘Sorry – I just need to treat this low.’

‘Sorry, darling. Would you mind just grabbing me a juice box from over there?’

‘Sorry – I had a lousy night with crap high BGLs and hardly slept. Would you mind repeating what you said? I missed it. Sorry.’

‘Sorry – my pump is wailing at me. Let me just see what it wants.’

‘Sorry – my CGM is alarming. I need to calibrate…hang on a sec…’

‘Damn. I’m out of insulin. Sorry. I just need to refill my pump.’

‘Sorry for munching on these glucose tabs. I’m okay – just trying to ward of a low.’

‘Sorry. My brain is foggy! I think I might be low….’

Sorry. Sorry. Sorry. Sorry. Sorry. Sorry. Sorry. Sorry…

Why am I apologising for my messed up beta cells? I didn’t destroy them. (Actually – technically I guess that’s not true. My own body did kill them off. But it wasn’t deliberate on my part…This is all getting rather confusing, so let’s just agree that it’s not my fault that I have diabetes.)

Why do I say sorry for having to treat or manage or address the health condition I live with all day, every day, and do things that I only do to keep me well…and alive?

I’m not alone here. Many others do the same. I’ve sat in rooms with friends having nasty lows and heard them apologise over and over again as they treat and will their glucose levels to rise. We do it amongst ‘friends’ – others from our pancreatically challenged tribe who get it better than anyone else, and we do it with those who are not living with it.

When I apologise for my diabetes, I am making it sound like I have done something wrong – intentionally or accidentally. And that is never the case. I’ve never intentionally been low or high. And even if it could be considered an accident or something I could have prevented – perhaps over- or under-bolusing or forgetting to refill my reservoir before leaving home – it was never done with the aim of being disruptive to others. Or myself for that matter.

What I am also doing is apologising for diabetes inconveniencing others. And I am also saying it is something shameful. But I can’t do anything about having diabetes. And it is not shameful. I am certainly not ashamed of having diabetes.

I wonder if it is a case of good manners going too far. Manners are very important to me – I have instilled this in our kidlet who is frequently complimented for her beautiful manners. But manners are about courtesy and respect – and that respect is for yourself as much as others. I think I am actually being quite disrespectful to myself when I apologise for having to ‘do diabetes’.

My body, which really doesn’t like itself, is not a reason for me to say sorry. I do enough managing diabetes without having to feel the need to repent all the time. So I’m not saying sorry anymore. Well, I’m going to try, anyway!

I can’t believe I wrote this piece almost seven years ago. I had turned 40 the year before and as often happens around the occasion of ‘big’ birthdays, I’d started to think about just what getting older means. I didn’t seem to have any feelings of regret or stress that I was ageing though, I was fully embracing just where I was going, the wisdom that I felt, and the absolute excitement of what was coming next. Seven years later, I can see that I was right to feel that way.

At the moment, I’m spending time thinking and reading about menopause and I’m lost in language that is tied up with this ‘next stage’. There seems to be so much loss, regret, and looking back, and feeling scared about what people are losing and leaving behind as the next stage of life hits. But I don’t feel that way. I feel that I can look back with pride and achievement and happiness and pain and love and hurt and longing. There are things I wish I had done differently, but nothing I wish I hadn’t done. I don’t want do-overs. Looking ahead, there is just more to look forward to, possibilities that I have no idea about yet.

This year, with so much about insulin’s centenary, thinking about getting older seems more poignant. Because a short century ago, diabetes was a death sentence. Ageing was only something we could even dream about. What a privilege to wear my age in years alongside my age in diabetes!

And so today, I’m sharing these words from 14 October 2014 (with a few edits) because they still ring true for me. They still feel real. And in seven years time, I’m hoping I revisit this post again, and feel the same way.

______________________________________________

I really should be careful what I read and where I read it! The other day I sat at a gate lounge at Sydney Airport crying as I read an incredibly candid piece on the Huffington Post that inexplicably told my story so honestly and accurately that I wondered if I had written it and not remembered.

And then I read this piece by Rebecca Sparrow and again, floods of tears as I nodded at everything she wrote.

I remember one day sitting with a group of other women all around the same age and we were speaking about skin care products (and then we giggled about boys, plaited each other’s hair and painted our toe nails). I was the only one who had not been using so-called anti-ageing products for a number of years. Because that’s the thing – we’re meant to be anti-ageing and do things to turn back the clock.

I am forty years old. (EDIT: forty-seven) This is not something I feel the need to hide nor be ashamed of. I celebrated last year with a week of parties and lovely gifts. I wanted to celebrate this milestone – just as I do every milestone. Next month, I turn 41 and have every intention of celebrating that too.

Rebecca Sparrow writes that ageing and getting older is a privilege as she tells the story of a friend of hers who, at 22 years has been diagnosed with terminal cancer. This young woman is not going to be afforded the opportunity to age and get wrinkly and turn grey. She is going to die at an age where most of us feel completely immortal.

Ageing is a privilege – I understand that more and more every day. With our daughter growing up – she’s going to be 10 next month – I can easily measure time. We see how she has changed and how, with each passing month, she is becoming an incredible young girl we are so proud of. And we are so lucky to be able to watch this.

I am over the idea that ageing is something that we should hide from and do everything in our power to avoid. I am forty years old. I look older than I did when I was 17 and doing year 12, or when I was 25, or when I was 30 and pregnant, or even than I did a couple of years ago. Of course I do. And if truth be known, I really don’t want to turn back the clock – on how I look physically or how I feel emotionally. With age comes wisdom – it may be a cliché, but it is true. But even more – with age comes experiences and confidence and a sense of self that only seems to grow each year.

Ageing is a privilege. It is normal. And devastatingly, for some, they never will age.

Less than 100 years ago, being diagnosed with type 1 diabetes was a death sentence. Think about that for a moment. If I had have been diagnosed prior to insulin being available, I would have died before I was 25 years old. I never would have travelled, worked in a job that gives me incredible joy, spent so much time with friends and family, seen Tony Bennett live, learnt what an octothorpe is, watched the West Wing, attended my 20 year school reunion – or my 10 year school reunion for that matter, danced on the turf of the MCG as The Police sang, seen the Book of Mormon, read Harry Potter, gone to (and fallen in love with) New York City, met Oliver Jeffers, used an iPhone, gotten married or had a daughter. (2021 EDIT: AND …revisited and revisited and revisited New York, watched my girl turn into the most amazing almost-adult, stood on the stage at conferences around the world, extolling the value of the lived experience, stood alongside three amazing women as we put together the fantastic programme for the 2019 IDF Congress, Living with Diabetes stream, celebrated 20 years of marriage, road tripped across the US with Aaron, visited Graceland, sat in ABBA’s Arrival helicopter, ‘built’ my own pancreas, gone back to Paris another few times, and finally been able to sit on the grass at Place des Vosges, taken my family to Friends for Life, seen the language matters movement grow from the seed we planted into a global movement, lived through (and continue to…) a pandemic…)

My life would have ended before any of these things. Just because I’d been diagnosed with type 1 diabetes. Which makes me understand and feel the privilege of ageing more and more. Every diaversary, every diabetes milestone is worth celebrating.

I want to look forty (EDIT: forty-seven) – I want every battle scar I’ve earned to be visible; every success – and every failure – to be shown on my face; the story of every victory and disappointment to be told. Because these are part of who I am and I am so, so lucky to be here to keep telling my story.

And Zooming. So fucking much Zooming.

Today, there was an article in online publication, The Limbic, which reported on a recent study conducted out of Westmead Hospital Young Adult Diabetes Clinic

The top line news from this research was that there is a high discontinuation rate of CGM in young people (aged 15 to 21 years).

Let me start by saying I know that CGM is not for everyone. I don’t believe everyone should use it, have to use or even necessarily be encouraged to use it. As with everything, your diabetes technology wishes and dreams may vary (#YDTWADMV really isn’t a catchy hashtag, is it?), and there is a lot to consider, including accessibility and affordability. In Australia, affordability is not such an issue for the age group that was studied in this research. Our NDSS CGM initiative means that access to CGM and Flash is fully taxpayer funded (with no out-of-pocket expenses) for pretty much all kids, adolescents and young people up to the age of 21, provided a healthcare professional fills in the relevant form.

The top-level findings from this research are that within the first week of starting to use CGM, almost 60% of study participants stopped. The decision to start CGM was made after a one-hour education program that was offered to 151 young people with diabetes, and 44 of them decided to start CGM. Of those 44, 18 young people continued using it. They happened to be the 18 young people who were more connected with their HCP team (i.e., had more frequent clinic appointments) and had a lower A1c, which the researchers suggested meant that they were struggling less with their diabetes management. The 26 young people who chose not to continue cited reasons for stopping such as discomfort, and inconvenience.

I had a lot of questions after I read about this research. (These questions arose after reading the Limbic’s short article and the research abstract. I will follow up and read the whole article when I can get access.)

If the young people who chose to not continue were already struggling with their diabetes management, is adding a noisy, somewhat obvious (as in – it’s stuck to the body 24/7), data-heavy device necessarily a good idea? Was this discussed with them?

Was any psychological support offered to those young people having a tough time with their diabetes?

Was it explained to the young people how to customise alarms to work for them? If diabetes management was already struggling and resulting in out-of-range numbers, high glucose alarms could have been turned off to begin with. Was this explained?

What education and support had been offered in the immediate period after they commenced CGM therapy? Was there follow up? Was there assistance with doing their first sensor change (which can be daunting for some)?

In that one-hour education they were offered before deciding to start on a CGM, did they hear from others with diabetes – others their own age (i.e., their peers) – to have conversations about the pros and cons of this therapy, and learn tips and tricks for overcoming some typical concerns and frustrations?

What was in that one-hour education program? Apparently, 151 young people did the program. And only 44 people chose to start CGM. Now, as I’ve already said, I don’t think CGM is for everyone, but 29% seems like a pretty low uptake to me, especially considering there is no cost to use CGM. Did anyone ask if the education program was fit for purpose, or addressed all the issues that this cohort may have? Why did so few young people want to start CGM after doing the program?

Were they using the share function? Did they have the opportunity to turn that off if they felt insecure about others being able to see their glucose data every minute of every day?

What frustrates me so much about this sort of research and the way it is reported is that there is a narrative that the devices are problematic, and that the people who have stopped using them have somehow failed.

CGM may not be for everyone, but it’s not problematic or terrible technology. I remember how long it took me to learn how to live with CGM and understand the value of it. It took me time and a lot of trial and error. I didn’t want to wear CGM, not because it was lousy tech, or because I was ‘failing’, but because I hadn’t been shown how to get it to work with and for me. I had to work that out myself – with the guidance of others with diabetes who explained that I could change the parameters for the alarms, or turn them off completely.

And these young people are YOUNG PEOPLE – with so much more going on, already struggling with their diabetes management, and not connected with their diabetes healthcare team as much as the young people who continued using CGM. Do we have any information about why they don’t want to connect with healthcare professionals? Could that be part of the reason that they didn’t want to continue using CGM?

I don’t think we should attribute blame in diabetes, but it happens all the time. And when it does, blame is usually targeted at the person with diabetes, but rarely the healthcare professional working in diabetes. If a person with diabetes is not provided adequate, relevant education and support for using a new piece of tech, there should not be any surprise if they make the decision to not keep going with it.

The positives here is that there is data to show that young people who are already struggling with their diabetes management may need other things before slapping a CGM on them. Cool tech can only do so much; it’s the warm hands of understanding HCPs that might be needed first here. Someone to sit with them and understand what those struggles and challenges are, and find a way to work through them. And if CGM is decided as a way forward, work out a gently, gently approach rather than going from zero to every single bell and whistle switched on.

I am a huge supporter and believer in research and I am involved in a number of research projects as an associate investigator or advisor. I’m an even bigger supporter in involving people with diabetes as part of research teams to remind other researchers of the real-life implications that could be considered as part of the study, offering a far richer research results. Growing an evidence base about diabetes technologies is how we get to put forward a strong case for funding and reimbursement, increased education programs and more research. But sometimes there seems to be a lot of gaps that need filling before we get a decent idea of what is going on because the findings only tell one very small chapter in the diabetes story.

Imagine if the only emotion we felt when we ate something was joy. How different that would be.

A more detailed post about language a food can be found here.

Diabetes is an invisible illness. Except, of course, it’s not.

If you look – carefully – around our home you will notice diabetes is everywhere.

Open the fridge and you will see insulin vials and the paper prescriptions for next time I am running low, housed in a blue box on the lowest shelf.

The pantry is stacked with juice boxes, fruit pastilles and other easy to digest sources of glucose.

Tell-tale signs on my bedside table include a jar of jellybeans, a half empty glass of orange juice and a BGL meter.

In the bathroom is the cannula I pulled out this morning before I stepped into the shower – so that I could enjoy the water on my body with one less piece of equipment taped to my skin.

My bag is a veritable treasure trove – if the treasure you seek is quick-acting glucose, old blood glucose monitoring strips and diabetes supplies…

In the bedroom there are the empty packages from pump lines and cartridges and CGM sensors, waiting to be disposed of appropriately.

A beautiful old cupboard housed in the corner of that same room look as though it should hold family heirlooms, but instead is dedicated to housing neatly stacked diabetes supplies.

In my study, on the bookshelf, you will see shelves dedicated to diabetes-related titles: books by friends and colleagues about how to live well with diabetes.

On my desk is a half-empty bottle of glucose tabs and glucose tab dust liberally sprinkled around.

My phone alarms and warns throughout the day, the volume turned low so as not to startle me while on a Zoom call.

There are pathology slips on the fridge, magnets holding them in place, reminding me to make time to get those checks done.

There is a pattern of red dots on the bed linen from the ‘splurter’ last night when I calibrated my CGM. Running late this morning I didn’t have time to change the sheets.

On the kitchen bench, where items for recycling sit before being taken to the bin, you’ll frequently see one, two, three empty juice boxes.

Tied around the rose bushes in the front garden you’ll find used pump lines, holding the branches to the fence.

On the fridge are messages and cards and silly notes from DOC friends from nearby and faraway, reminding me that I have support around the globe.

And everywhere, but everywhere, you’ll see an odd BGL strips, glittering (littering) the ground.

Diabetes is invisible until you look for it. And when you do – and when you see it – you realise that diabetes lives here.

Today is about numbers.

I am celebrating 23 years of living with diabetes.

8539 days of living with diabetes.

1,537,020* diabetes decisions.

It’s no wonder diabetes is so exhausting.

Today is also about the number 98, because 98 years ago, diabetes became commercially available for the first time. This was all very much in my mind in the middle of last night when I was wide awake, not because I was dealing with my own diabetes, but rather because I was speaking at the World Health Organisation launch of its new Global Diabetes Compact.

This year is all about the number 100, celebrating the centenary of insulin…100 years since 4 scientists, Banting, Best, Macleod and Collip, discovered insulin – the reason I am alive today.

There is a lot to celebrate, but at the same time, there is a lot we need to acknowledge that isn’t so great. People with diabetes are still dying because they cannot access insulin and other drugs, diabetes consumables and healthcare. The number 12 is also relevant, because it remains the average number of months that a child born in sub-Saharan Africa will live once diagnosed with type 1 diabetes.

I don’t know the number of diabetes friends I have, but, damn, that number, and the people included in there, is one of the most important for me. The 4 diabetes friends who continue to keep a diabetes group chat alive every single day give me life, even if we are so many miles away.

The numbers 1 and 2 are important, but they are not the only numbers that refer to the different types of diabetes.

As I type, the number 5.4 is showing on my Loop app, and so is 3, representing how much insulin remains in my pump which means I’ll need to take 5 minutes to refill my cannula.

My husband and daughter are the 2 people in my world who see my diabetes all the time, support me through it, love with despite it. There is no numerical way I can define how much their love means to me. (And the 2 dogs and 1 cat couldn’t care less about it…!)

Today is also about the number 1. Me. This year isn’t a particularly monumental diaversary number – it’s not one that ends in a 0 or a 5 which seem to be the ones that I celebrate more. And yet, I do feel that it is worth acknowledging and celebrating. Which I’ll do – in between the 180 diabetes-related decisions I’ll be making.

*When I calculated the number of diabetes-related decisions I have made over the last 23 years, I automatically started singing ‘Seasons of Love’. Here is my beautiful friend, Melissa Lee’s stunning diabetes version of this song. (I cry every time I watch it, so I advise having some tissues handy!)

Non-Aussie friends may not get the reference in the heading to today’s post. Our Prime Minister loves to pretend to be at one with the people by excitedly declaring ‘How good is Australia’. But right now, in reference to the global COVID vaccine rollout, Australia is not good at all. In fact, I’d say we’re pretty bloody hopeless. My heart breaks for the sacrifices we all made last year that have resulted in us being pretty much at zero COVID – something the PM can take no credit for considering he wanted us to ‘learn to live with the virus’.

But to answer the question posed in my post title literally: COVID vaccines are fucking amazing. A well-vaccinated population is the only way we get out of this pandemic, and the data on the vaccines is very promising.

What is not good is the complete and utter bungling of the rollout that we are dealing with here in Australia. We started late; accessing a vaccine is proving impossible for many people; quarantine and front-line workers have not all been vaccinated as a priority, GPs don’t have vaccines available for their clinics; there remains a risk of the vaccine escaping hotel quarantine settings into a largely unvaccinated community, and, it seems, that we have limited quantities of vaccines available. Plus, the decision to effectively put too many vaccine eggs in one basket has backfired due to the changing advice regarding the AstraZeneca vaccine. To top it all off, the comms plan has been a debacle – and continues to be, most recently with the PM having decided that Facebook will be the channel he uses to update the public on our now non-existent vaccine targets. (He also told us to not use Facebook as a source of information, but I guess that was a few weeks ago, and we need to keep up with the merry-go-round.)

Unsurprisingly, a lot of people are concerned, confused and unsure of what they should be doing. While the information that was released in a hastily organised presser at 7.30pm last Thursday night wasn’t all that much of a surprise, considering what was unfolding in other countries, some people started to feel a lot of unease. There has been a plenty of discussion in online diabetes groups about what the best course forward is. While the Pfizer vaccine is the preferred choice for anyone under 50 years (here in Australia – it’s different ages in other countries), there is very limited Pfizer available. If you are under 50 years, you can still choose to have the AZ vaccine if that is all that is available to you, however both NSW and Vic have currently stopped giving AZ to anyone under 50 until there is revised informed consent materials available.

I had my first AZ vaccine three weeks ago after spending three hours on the phone finding a GP clinic that had available doses and would see me if I hadn’t already been to the clinic. I had no side effects at all. Both my parents and parents-in-law have had the AZ vaccine and I know a lot of people in the diabetes community both here in Australia and overseas who have had it with, at worst, typical side effects. At a breakfast the other day with some Loopers, three of us had already had the AZ jab and none of us had reactions. I will be very confidently and happily rolling my sleeves up for my second jab in June, so that I can be fully vaccinated.

For me there is a simple equation that I used to make my decision, and for the assurance I feel. As a person living with diabetes, the risk of complications from COVID if I were to catch it are far greater than the risks of an adverse event from having the vaccine. It’s that simple. Plus, I have a responsibility to get the vaccine because there will be people in the community who cannot, due to (real) medical reasons.

The question for people with diabetes now – especially those under 50 years of age – is what does that equation look like for them. What is their risk assessment? The likelihood of a blood clot after an AZ jab is tiny, but there are some people who are at an increased risk. How does that weigh up to the chance of getting COVID – and the complications that may follow – if there is another wave?

Right now, it’s understandable that there are people with diabetes who are feeling very anxious about that possiblity of another wave as we head into colder months, and also not being able to get vaccinated, or being very unsure about whether they should have the AZ vaccine. Diabetes Australia has offered this advice for people with diabetes, and at least one thing that is consistent from all reputable sources, is that the chance of a clot is very, very small.

For anyone minimising the concerns that some people may be feeling, just remember that it is people with diabetes who were included in the ‘Everyone will be fine as long as you’re not old or unwell’ statements that were common when COVID started over twelve months ago. The impact on the mental health of people who started to feel disposable is very real. Those statements are still around, although some people added ‘Well YOU can stay home until you can get a vaccine and let the rest of us get on with things.’ That’s all good and well…if the vaccine rollout was working. It is not.

This is a troubling time. Australia’s record with COVID has been excellent, thanks to outstanding leadership from our state governments. It is a shame that, according to this article from The Monthly, we are now faced with the likelihood of another wave of the virus, more lockdowns, and travel restrictions for a number of years to come. How good are COVID vaccines? They’re bloody brilliant. But only if they’re in the arms of people.

More musings on vaccines

This about how vaccines don’t cause type 1 diabetes.

When I was planning for pregnancy, and while I was pregnant, I read everything I could about how pregnancy might impact on diabetes (and vice versa). There is a lot of information out there about pregnancy and diabetes (especially pregnancy and type 1 diabetes) I wrote this online diary sixteen years ago, with weekly updates throughout my pregnancy. Heaps of new parents with diabetes share their early parenting stories – with great tips about managing glucose levels during those new days of having a small person completely reliant upon you, while having to manage a health condition that is also reliant upon you!

But what happens when your kid is older and the impact of diabetes on a daily basis seems to be less? It doesn’t seem all that relevant really, but I do wonder if there is a long-lasting impact that I don’t consider. Just how has diabetes influenced the way I parent? Indeed, has it impacted at all? And has diabetes affected my relationship with my daughter? What does it mean for her to have a parent with diabetes?

It’s not my story to tell from the perspective of my 16-year-old daughter. I have asked her many times what it’s like having a mum with diabetes; what it’s like having been around diabetes all her life. One day, she might like to share her feelings with others, but they are her feelings and experiences and I completely respect that it is not my job to share her thoughts. Plus, my interpretation will always be clouded by my own version of events, and my own fears and biases.

When she was younger, my diabetes and its impact on my daughter caused me a lot of unease. I have never stopped worrying that I have passed on my messed-up DNA to my daughter, but it was more of a regular concern (panic?) when she was small. I spent a lot of time with a psychologist learning how to rein in those feelings because they spilled out a lot into anxiety and fear. I had to understand that those worries were about me and my feelings of guilt, not about her – something she told me without hesitation one day when I wanted to check her glucose (for probably no good reason).

These days, I rarely find myself questioning how much water she is drinking or wondering if she seems to have visited the loo more frequently than usual. Perhaps it’s because I feel confident enough that she knows the four Ts – of course she does – and if she ever were concerned, she would come to me. Or make an appointment to take herself off to the GP. (In those moments when I have noticed that I am starting to get really concerned about this again, I make an appointment to see my psychologist, because sometimes I do need help to keep things in perspective and keep the dread at bay.)

One way that diabetes has definitely clouded the way I parent is how I respond and react to times she is feeling poorly. I am not a sympathetic parent – mostly because diabetes has taught me to just get on with things – even when it is being a royal pain in the arse. I jump to a diagnosis of hypochondria any time she says she’s not feeling well. (To be fair though, that is my diagnosis for anyone claiming to feel unwell, not just my own child).

I was not a parent who, when the kidlet was an accident-prone toddler, jumped at every tumble or scratch. Sympathy is hard to come by with me – a point she made keenly when she was about three years old and tripped as we wandered down the street. She responded to my ‘Oopsie, up you get,’ with a tear-stained, overly dramatic ‘Just once I’d like you to ask me if I’m okay.’ I promised that if there was gushing blood or a visible bone sticking out that I would ask her if she was all good. But otherwise, up you get and off we go to the park.

Living with diabetes and the needles that come with it has meant that she doesn’t even get to voice any nervousness when it’s vaccination time. My ‘toughen up princess’ approach to even the start of a frown because a needle is imminent has taught her to not even go there! That sympathy will need to come from persons who do not jab themselves on a daily basis.

My Italian mamma tendencies do show up with bowls of steaming chicken soup for runny noses, and pastina con burro for tummy aches. But once they are prepared and consumed, there is an expectation that life goes on without moaning or much downtime. I think my own parents find me a little mean, but they more than make up for it by piling on sympathy and compassion, while muttering about what a cruel and indifferent mother she has.

Understanding my need for the right HCPs at the right time has meant that I’m more inclined to outsource than do things myself. I can’t count the number of times I’ve asked if she would like to see a psychologist because surely, the angst of the tween years or the teen years, or any of the obviously nightmarish parenting she has had to deal with is far better dealt with by a professional. But instead, she has seemed mostly happy enough to chat over homemade cookies and a cup of tea when she has needed to talk something out, so I guess that my nasty, unsympathetic ways haven’t resulted in her thinking that she can’t confide in me when she wants.

I write a lot of this very tongue in cheek, but I do believe that it is impossible to live with a chronic health condition like diabetes and not have it somehow impact on all relationships, including those with our children. Having diabetes and getting pregnant – and then holding on to that pregnancy – was probably the hardest thing I have ever done, but it is also the most wonderful, incredible, important and worthwhile thing I have done. Fertility difficulties before and after that one successful pregnancy have made me acutely aware of just how fortunate I am, and not a day goes by where I don’t, at some point, think that, and marvel at the amazing human I have a front row seat watching grow into a truly remarkable person.

Because in amongst it all, I also wonder if diabetes will rob me of some time with my beautiful girl. Will it cut short the number of years I get to be with her? What will I see? How much of how her life turns out will I be witness to?

These days, I think that is probably what scares me most about diabetes – that I won’t get to have as many of those years and see as many successes and struggles as I hope to. Which makes me horribly sad, because the first sixteen years have been nothing but a delight. Of course, I love her – I adore her! But also, I really like her. I want to be around for as long as I can and to see as much of that as possible. I fear that diabetes will be limiting – limit what we can do together, and simply minutes, hours, days, years together. It’s these thoughts that are locked away in the dark parts of my mind and don’t get to see the light of day much. Because when they do, I feel a sadness like no other and a terror far bigger than anything I have ever had to face.