You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Healthcare team’ category.

This post was first published in 2011. Sometimes, I think that there is progress being made when it comes to consulting people with diabetes in the development of programs, services and resources for us. Other times, I’m not so sure. Some groups and organisations are incredibly tuned in to people with diabetes (I’m talking about you, Australian Centre for Behavioural Research in Diabetes) and I cannot express enough my gratitude for the high regard of the ideas and thoughts of people with diabetes this group regularly demonstrates.

I stand by what I have written in this post: We are the experts in living with diabetes and we want to work with those who are working to help us. Please, please let us.

——————————

There seem to be a lot of people who like to be the voice of people living with diabetes. Strangely enough, a lot of the time, these voices don’t actually have diabetes themselves.

As far as I am concerned, every single person out there who wants to advocate and support people living with diabetes is terrific. Continue doing it! But make sure that if you are speaking for us you have first heard what we want to say.

Any time an advisory panel or steering committee looking at anything to do with people living with diabetes is formed, the first people invited should be consumers. How can other people possibly advise or steer for us unless they hear what we need and what we want?

If government wants to improve our lot, ask us how to do it.

Experts in diabetes are not the people who care for us. I know how blunt and arrogant that sounds, but it’s true. I have a brilliant team of health professionals around me – I have written of this on several occasions; hell, I even named my daughter after one of them. But these outstanding, talented, exceptionally smart people do not speak for people with diabetes.

I struggle regularly with the way that we are not considered in the planning and development of new resources, activities, devices and technology designed to ‘help us’. When we pipe up and say ‘hey we’re here’, we often get told that we’ll be consulted ‘later’ – often too late when changes cannot, or will not, be made. That sort of consultation is, I’m afraid, tokenistic. It doesn’t count for anything and those doing this shouldn’t get to then say that they did work with the community.

The experts when it comes to making lives better for people with diabetes are us. The people with diabetes. We’re the ones who live with it, love with it, scream at it and want to turn our backs on it in disgust. We’re the ones who agonise, cry, laugh and celebrate it.

Don’t speak for us. Don’t assume. It should always be nothing about me without me. Always. Listen to us. Ask us. Take cues from what we say. Believe me, we’ll tell you what we need.

Am I being too harsh with this? I wonder what others with diabetes have to say and if they feel the same way.

Do a Google search of the term ‘empowered patient’ and you will be inundated with thousands and thousands of links defining the empowered patient, instructing how to be an empowered patient or advising how to deal with an empowered patient (run for the hills and refer them on to another HCP). Health conferences have sessions dedicated to patient empowerment, there are countless social media sites and blogs on the topic, and there are many journal articles – written from the perspective of both the patient and HCPs about what patient empowerment means in healthcare. It could be considered a buzz term, even though it’s been around for some time.

Health organisations for conditions from diabetes to Sjögren’s syndrome(look it up!) dedicate pages of their websites, events and resources to guiding people to become empowered and ‘own’ their condition. It’s not a new thing, and while embraced my many, is still treated with some scepticism and nervousness by some and dismissed by others.

I am what I (and most) would call an ‘empowered patient’. Whilst, I acknowledge that the term is widely understood, I’m not sure that it really is a term with which I’m comfortable. Perhaps because the empowered patient can be considered difficult and annoying – a know-it-all who is there to try to take over the expertise of their HCP. That’s absolutely not what I am trying to do with my healthcare. When it comes to diabetes, I am the first to say I know nothing about diabetes – that’s why I see an incredible endo. But MY diabetes? I am the Universe’s leading expert in that!

For me, being an empowered patient simply means that I am in the driving seat as well as being navigator of my health issues– primarily diabetes, but also other things as well. (Last year, I demanded that I have a D&C following a miscarriage despite the OB wanting to just ‘wait and see’. Waiting and seeing for me would involve horrible pain; excessive bleeding and dealing with the miscarriage whilst on a long haul flight back home from NYC. Previous experience told me that. So I made sure that my wishes were not only known, but also carried out.)

In sixteen years managing diabetes there have been very few instances where I have blindly followed medical advice without asking questions, weighing up all possibilities and talking with others about their experiences.

But I wonder how much being empowered about my health condition and active in decision making is simply because that’s the sort of person I am. When planning for anything, I am organised and informed. I seek out the right people to speak with, I consider options, I ask a lot of questions. I make decisions based on what I have learnt and what I think will be best for me. Whether it is planning a holiday, choosing a contractor or looking after my health, I empower, educate myself. It’s my personality; it’s how I roll.

So does it mean that people who are not naturally like this miss out on the choices and options afforded to people who seek them? Does it mean that if someone is unable to empower themselves (perhaps because of language or cultural barriers, their personality or a lack of understanding of, or an inability to navigate the system) they wind up with substandard care?

Being an empowered patient isn’t at the expense of the expertise and knowledge of the HCP experts we’re working with. It helps form a partnership. I honestly do believe that it is because of our empowerment – our demands and expectations – that we receive better care, better options and, possible, achieve better outcomes. We make our HCPs accountable and answerable, but more than that, we make ourselves accountable and answerable. Sharing in the decision making means we also have to take responsibility when a medical treatment doesn’t necessarily work out the way we hoped. But I’m willing to take on that responsibility.

I was recently sent an article from Medscape that was written by Svetlana Katsnelson MD, endocrinology fellow at Stony Brook University Medical Center in New York.

The gist of the piece is that for a week as part of her endocrine fellowship training, Dr Katsnelson wore an insulin pump and checked her BGLs, and now believes she knows about living with diabetes. She also considers herself non-compliant because she didn’t bolus for an apple.

This may be oversimplifying the article a little and I honestly do believe that the intention here is good. But a little perspective is needed, I think. It was this comment that really upset me:

‘The experience provided me with a better understanding of how to use the devices that many of our patients use every day, but it gave me much more than that. I truly began to understand how difficult it is to live with diabetes.’

No, Dr Katsnelson, no. You do not truly understand how difficult it is to live with diabetes.

What you have is an idea of what it is like to walk around with a device delivering non-life saving saline into your system. You also have an idea of how it sometimes hurts when a sharp object pierces the skin on your finger. You probably could have deduced that anyway because, you know, sharp object, skin, nerve endings etc. You know how the buttons of these devices feel under your fingers and the weight of the devices in your hands.

You may have an idea of how tricky it can be to accommodate a pager-like device if you are wearing a pretty, flowing dress to work (if that is your want). You may now understand how annoying it is to have to stop what you are doing because it’s time to do a BGL check.

But what you don’t understand is that diabetes is about so very much more than that.

Here is what you don’t have any idea about.

You don’t understand the feeling of ‘this is forever’ or ‘I never get a holiday from this crap’. I know that this was acknowledged in the article, but really, you don’t know how it feels to never be able to escape diabetes.

You have no concept of the boredom of living with a chronic health condition, or the monotony of doing the same tasks each and every day over and over and over again!

You don’t understand the fear that overtakes your whole being as you imagine all the terrible complications that have been threatened and promised as result of diabetes.

You have no notion of the frustration of living with a condition that doesn’t have a rule book – and in fact changes the rules all the time!

You haven’t any perception of the fear I sometimes feel that I’ve passed my faulty genetic matter onto my beautiful daughter; or that I am a burden to my family and friends.

You will never feel the judgement from healthcare professionals because numbers are too high or too low – or that there are not enough of them.

You will never be called non-compliant by a doctor or made to feel guilty because you are eating a cupcake – all because your beta cells decided to go AWOL.

While I really do commend the notion of HCPs trying the ‘day in the life’ (or ‘week in the life’) idea, I think that being realistic about what this experience provides is important. It does not give any insight into the emotional aspects of living with a chronic health condition. It doesn’t explain the dark place we sometimes go when we are feeling particularly vulnerable or ‘over it’.

I have to say that all in all, this article left a sour taste in my mouth and I don’t like to feel that way because it sounds like I am being Grouchy McGrouch. I’m not. And as I said, I think that the intention here is good.

I just don’t want Dr Katsnelson to think that she now knows what is going on in my head when I wake up at 4am and every terrible scenario plays out leaves me feeling a pressure on my chest and a blackness in my mind that threatens to overtake me.

But I also want Dr Katsnelson to know that I really don’t expect healthcare professionals to know and understand all of these things. I expect them to treat me with respect and dignity. If this exercise has helped that, then great, but please, call it for what it is.

The article discussed in this post (Svetlana Katsnelson. Becoming the Patient: Not as Easy as It Looks. Medscape. May 12, 2014.) can be accessed here by first creating a free login.

Last Friday I attended a couple of sessions of the Health Professional Symposium coordinated by Diabetes Australia – Vic and Baker IDI. The packed program covered a variety of topics including cognitive function in children with type 1 diabetes,musculoskeletal complications of diabetes and a panel discussion about whether lifestyle interventions are an effective approach in diabetes management.

The two sessions of particular interest to me were around diabetes in the hospital setting. The first, from DNE Sue Wyatt (Alfred Hospital), focussed on improving diabetes management in hospitals (including discussions about outcomes, policies and procedures) and the second was from dietitian Anita Wilton who discussed food services in hospitals.

To me, both sessions highlighted the problems faced by many people with diabetes when we are admitted to hospital – whether it be for a planned stay or emergency visit. The outlined policies and procedures do not take into account that people with diabetes have different levels of understanding, knowledge and self-management, and the ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach is, I believe, actually detrimental to diabetes care (indeed, diabetes self-care), emphasising the artificial environment experienced when in a hospital setting.

There needs to be a balance between what we as people living with diabetes need when we are in hospital and how we fit into the ‘rules’ and regulations enforced in hospital.

And one issue of particular concern is what happens to our insulin (and other medications), delivery devices and other management tools (BGL meters etc.). At the Alfred Hospital, insulin and delivery devices are taken from the patient. Obviously, this isn’t the case with pumps, but pens and syringes are removed from the person with diabetes and locked away. This is the policy and according to Sue Wyatt, in only one case has this been challenged to the point where the patient was allowed to hold on to their medications.

Unsurprisingly, this doesn’t sit well with me at all.

I raised my hand during question time to ask about how we manage the different needs of the person living with diabetes and hospital policies and procedures that, in this case, go against everything I believe in when it comes to patient empowerment. The answer I received was all about protecting the nurses in the hospital setting and whilst I completely understand and respect the need for that, where was the discussion about protecting the rights of the patient? At no point, when I am a patient, do I give up those rights. I understand that there will be times that people with diabetes are unable to administer their own insulin, but for many, that is not the case. As they are recovering from surgery or sitting in A&E dealing with whatever they are dealing with, managing their own medication is not only possible, but frequently the best option.

In my case, I have never been an inpatient and unable to administer insulin (after calculating doses and entering the correct information into my pump). Being able to address high BGLs and correct accordingly, bolus at the exact time I am eating or treat a low immediately have actually meant smoother management whilst in the hospital setting rather than relying on an already-far-too-busy nurse.

Obviously, it is essential that hospitals have policies and procedures in place, but at the same time, the primary concern should be what is best for the patient. If the talk around patient-centred care is to be taken seriously (and not just perfunctory jargon to make people believe they are talking the politically correct language and saying the right things) then we need to make sure that the patient and their best interests are actually being contemplated.

At no time are my best interests being considered if I am asked to hand over all the things that I need to manage my condition, whatever the setting.

I am employed by Diabetes Australia – Vic. I was not involved in the planning or presenting of any sessions at this event.

Yesterday’s post about waiting to see my GP for 90 minutes past my scheduled appointment received some interesting comments and feedback both here on the blog and on Facebook and Twitter. Most people seemed to agree that the GP clinic displayed a lack of courtesy in not calling to let me know of the significant delay I was about to experience because my doctor was running so behind schedule. There is a great comment from a doctor providing the ‘other side’ of the story which makes for some interesting reading.

When I eventually was seen by my doctor, he apologised for the wait. He was incredibly sincere and said that it was ‘just one of those days’. I asked him what was the clinic’s policy when doctors were running considerably behind and he said that reception staff should call patients to let them know that there would be a wait, and inform the patient of the time they should show up to avoid sitting in the waiting room for too long.

He was upset – and very apologetic – that this had not happened in my case, and said that, quite simply, it was not good enough to expect people to wait for so long. He followed it up with the reception staff after my visit. And I spoke with the receptionist too as I was settling my bill. She said that they had been calling some doctors’ patients that morning, but not my GP’s. She also apologised.

So the wash up in all of this isn’t really that I had to sit around for 90 minutes. It’s that as a person who, unfortunately, has to spend far more time than I’d like to scheduling and attending doctors’ appointments, I do all I can to streamline the process as much as possible. I also understand the system – just like many other high-users do and try to manage it as best I can.

I was more than satisfied by how my GP dealt with the situation yesterday. There is a great comment on the blog from Rosie Walker who said if ….everyone’s time is considered equally valuable…. there will be acknowledgement, explanation and apology for people who are waiting and effort made to try to address the situation, invite suggestions or comment on how things could be improved. Really, that is all that I am asking for.

Last week, I attended a workshop given by Rosie Walker who is a UK-based diabetes and education specialist. You can read more about Rosie and her independent company Successful Diabetes here. The focus of the session was diabetes consultations and I was eager to go along as the ‘consultee’ as opposed to the consultant (most of the other participants).

One of the topics was how consulting rooms can be more ‘patient-friendly’. After this discussion, I asked if we could, for a moment, steer the conversation to waiting rooms.

I see my endo in private rooms and there is nothing particularly offensive about the room I wait in until she calls me in. It’s quiet, there are plenty of chairs and some out of date magazines on the table. I’m always pleased that there are travel mags, so I can do a little armchair travel as I while away the time.

My GP’s waiting room is a little more bustling. It’s larger, the phone doesn’t stop ringing and, because it is a very busy practise, people come and go constantly. There are signs on the walls asking people to not use their mobile phones while waiting to see the doctor in an endeavour to keep some of the noise down. The magazines are about health and wellbeing or home renovation. And golf. Someone in the clinic is a golfer and recycles their mags in the waiting room. Again, pretty innocuous and not an unpleasant way to spend some (often considerable) time waiting for my name to be called.

But I have seen some slightly terrifying things in waiting rooms that have made me want to turn around and walk out. Once, in a presentation I was giving in the waiting room of a diabetes clinic, I did actually draw attention to the horrendous poster which depicted graphic images of amputated toes.

I am not sure who thinks that it is a good idea to put up scary photos of ‘what will happen if you defy me’ in waiting rooms. Is there any logic in showing photos of amputated limbs, eyes with diabetic retinopathy or terrifying slogans of ‘diabetes is deadly serious’? Does this make people skip into see their doctor eagerly, or fear they may be threatened? At its worst, it’s akin to bullying. At best, it’s thoughtless and unnecessary.

Often, people sitting in waiting rooms are already anxious and scared about what is waiting for them. Will there be results from tests that could be bad news? Will the HCP be cross because diabetes hasn’t really been a priority lately? I know that I am often apprehensive about what is waiting for me behind the doctor’s doors and I don’t do HCPs who do judgement.

Waiting rooms need to be a safe haven, free of judgement, nastiness and fear. They need to calm us down and make us feel that we can be open and honest once we get to see the doctor.

For me, my dream waiting room would look like this:

Lots of natural light so I can see outside; not too much noise, but equally not so silent that I’m afraid to speak; details about relevant information events coming up; a barista in the corner making the perfect coffee (I said DREAM waiting room); comfortable chairs; free wi-fi; no TV blaring health messages (although, one of my HCPs does have Bold and the Beautiful on loop, so I get to catch up on that when I’m in their waiting room once every 12 months); gorgeous prints on the walls (absolutely no scary photos); a pin board with research news.

In lieu of perfection, however, I’d just be happy with a comfortable chair, some architecture and house porn and a water station. And a lovely, non-judgemental HCP on the other side of the door.

What do the waiting rooms you’ve spent time in look like? What would you like to see?

When I was growing up, our family GP was a crotchety, tiny man who seemed old to me when I was a kid. Given that he is still working today, he can’t have been much older than I am now (eeek!). The main things I remember about him is that he prescribed antibiotics at pretty much every visit, wore lifts in his clunky shoes to make himself taller and chain smoked during appointments.

As soon as I was old enough to choose my own doctor, I found a GP who I was comfortable with. She was the doctor I saw that April in 1998 when I told her my symptoms and asked to be tested for diabetes. She was the doctor I saw the day after Easter to get my blood test results. And she was the doctor who diagnosed me with type 1 diabetes with the words ‘Fuck. You’ve got diabetes.’ She was a good GP, but had an unhealthy interest in anti-ageing medicine and plastic surgery. I let her go after a consultation where she had to kneel on a seat for the entire visit because she’d just had liposuction and couldn’t sit down. Dealing with my own body image issues, I wasn’t sure that having a GP who was so focused on improving her body using surgery was sending me the right message.

After that, I spent some time drifting from clinic to clinic, rarely seeing the same doctor. It wasn’t ideal, but it did the trick.

A couple of years after I got married and a couple of years into my diabetes journey (the never-ever-ever-ending journey of diabetes) I was living across town and thought it time to find a local GP. Dr H had been recommended by a few people, so struck down with a virus that wouldn’t quit, I called to make an appointment.

‘Dr H is not taking new patients at the moment,’ said his incredibly officious gatekeeper. ‘We’re one doctor down for the next month. He won’t be seeing new patients until then.’

‘Great! I’ll take his first free appointment he has next month,’ I said.

‘And what will you be seeing Dr H about?’

‘Well, probably nothing then. But I want to get my name on the books. Plus, I have an exciting (i.e. senseless and convoluted) medical history. I’ll need some time to explain it to him’.

The next month, with absolutely nothing wrong with me, I sat in the waiting room avoiding the sniffling, coughing masses as I waited to see him.

I was pleasantly surprised to meet a doctor who understood that his role in my diabetes was not to manage it in any way. After providing satisfactory answers to his questions about the HCPs I worked with to help me with my diabetes, he explained that he saw himself as the traffic cop of my general health who could direct me in the right direction if I needed to see someone other than him.

I showed him my insulin pump – it was the first time he’d seen one. (This was 13 years ago now and pumps were still quite uncommon.) He asked me lots of questions about it and my other medical things and I left feeling that I now had a GP who would understand what I needed.

About eight months later, I made an appointment to see him. He called me in and followed me into the waiting room. Before I’d even had a chance to sit down he said ‘Where’s your insulin pump? Don’t you wear it anymore?’ The first time I’d seen him, it was strapped to the belt of my jeans. Since then, I’d started wearing it down my top, hidden from view. ‘Oh, good! I have a lot more questions,’ he said. ‘I’ve done some reading up and I was wondering if you could explain a few things to me.’ At that point, I realised he was a keeper!

I see Dr H only a couple of times a year. He always asks general questions about any correspondence he’s received from my endo or other HCPs. I am sure next time I see him, he will ask me about my recent cataract surgeries. But he knows that in my case, diabetes is not his concern – I have that taken care of.

I frequently hear stories of GPs who simply don’t understand diabetes. I hear of misdiagnosis after misdiagnosis and, quite frighteningly, of GPs who have such minimal understand of type 1 diabetes that it puts their patients in danger. Dr H has enough understanding of type 1 diabetes to know that it’s not his place to manage it. He says he always refers people with type 1 to an endocrinologist as they, along with the PWD, are the ‘content experts’. He doesn’t ‘blame’ diabetes for every medical complaint I present with. As I said, he’s a keeper. If only it wasn’t so bloody hard to get an appointment with him!

On Saturday night, before delving into the craziness that was White Night, I attended the launch of a terribly exciting new resource. Enhancing Your Consulting Skills; supporting self-management and optimising mental health in people with type 1 diabetes is described as an ‘education resource for advanced trainees in endocrinology and other interested health professionals’. That’s right. It’s written for health professionals who will be working with and for people with type 1 diabetes.

I attended with a dear friend who shares my pancreatically-challenged state. We also share the same endocrinologist – one of the collaborators on the resource – and were there at her invitation. We know just how lucky we are to see an endo who understands self-management, ‘gets’ the fact that burnout happens and doesn’t have a judgemental gene in her body. We know that having an endo who we can email in between appointments is a privilege we would never abuse. And we know that living in the inner city means that we have access to healthcare that many others can only hope for.

Hopefully, this resource will mean better education of new endo trainees and that the care we are so fortunate to receive will be available to many more people with diabetes.

This resource is a huge step forward in medical education. It is the first time that the needs of people with type 1 diabetes have been directly addressed with a strong focus on self-management and mental health. As Professor Alicia Jenkins highlighted in her speech, people with type 1 diabetes spend, on average, three hours per year with their healthcare team. The remainder of the time we’re doing it alone. There is no treatment option other than self-management and an understanding of how HCPs can support that is critically important.

Endocrine trainee, Michelle, gave a candid speech how she has come to view people living with diabetes. She said that when she first started attending a young adults with diabetes clinic, she was frustrated and said that she blamed her patients for not getting the results she expected. This honesty was refreshing and it was so pleasing to hear how she now knows to focus on the positives rather than negatives when working with PWD.

Dr Jennifer Conn gave a warming speech about how she never stops learning from her patients. This humble attitude is one of the reasons that this book is so well written. It acknowledges the expertise held by the person who lives with diabetes and knows their condition better than anyone else possible could.

I looked around the room and saw that there with the glitterati of the diabetes HCP world, were some of the pancreati – the people with diabetes who the book was written for. It’s a tribute to the writers and organisers of the launch event that people with diabetes were invited.

I’d like to congratulate the team who have put this together, and the NDSS for supporting the development of the resource. This is a win for people with type 1 diabetes and I can certainly see similar volumes being written for type 2 diabetes and, indeed, other chronic health conditions.

At the end of the event, I wandered back out onto the Melbourne streets, waiting for nightfall when the city would light up and fill up with hundreds of thousands of people. I looked at my friend and thought how lucky we are – a night of Melbourne brilliance kicked off with hope for a better future for people with diabetes.

Disclaimer

One of the collaborating writers involved in this resource is my endocrinologist. I was asked to provide comment on some sections of the book and my photo and a screen shot of this blog are included in the final book. I did not receive any payment for any of this involvement.

The development and printing of this book were funded by the National Diabetes Services Scheme (NDSS) which is administered by Diabetes Australia. I am employed by Diabetes Australia – Vic.

A couple of weeks ago at the ADS ADEA conference, I spoke at one of the Symposia about how healthcare professionals can get involved with diabetes social media. Today, social media has the ability to connect people like never before and is something about which I am passionate. I speak and write regularly about the power of the diabetes online community (DOC) as a way to bring together peers; my presentation at the Doctors 2.0 and You conference in Paris back in June discussed how social media can be used to connect four of the players in healthcare – patients, healthcare professionals, healthcare organisations and industry.

I was a little nervous about discussing this topic because I know how reticent a lot of HCPs are when it comes to social media and its value to people living with diabetes. Because of its very nature, social media is unregulated. There is just so much out there; how is anyone meant to know where to direct people? And equally, what should be given a very wide berth? (For the record – anything claiming that cinnamon cures diabetes is a crock and should be ignored!)

But actually, that wasn’t what my talk was about. My talk was about why people with diabetes turn to social media; what (and who) we look for and what we get from an online community of peers that we can’t necessarily get from our HCPs. I then moved to discuss how HCPs can engage with the very same things we are using.

My presentation was gentle – a lot of the people in the room had never considered using Facebook as a tool to provide support and connect with others living with diabetes. Whilst there is a general understanding about the value of peer support, that view is often out-dated and focuses on a more traditional picture – face-to-face support groups.

I discussed how health professionals around the world use social media as a mechanism to connect with other health professionals and how crowdsourcing diagnoses works. I suggested the audience look up Bertalan (Berci) Meskó and consider enrolling in his online Social MEDia course.

I explained how Twitter is about far more than finding out what Kim Kardashian ate for breakfast and discussed weekly diabetes tweetchats, urging the HCPs to check in, lurk for a week or two and then take part.

Social media works for people with diabetes because it feels like a safe place. I know that idea is completely contrary to what many HCPs believe – they see it as anything but safe! But I know that I can log on to Twitter or Facebook at any time of the day or night and there will be someone there who can say to me ‘I know how you feel’. There will never be judgement; there will never be accusations of not trying hard enough. But there will be support.

And I guess that’s the crux of this. We know our community and we feel safe there. In his TED talk, Berci Meskó discusses how crowdsourcing works when you know your audience and your social media networks.

The final thing I discussed was diabetes blogs. There are two ways HCPs can use blogs. The first is for themselves; they can read them; they can take in what people are saying. Because it’s by reading the blogs of people living with diabetes that the real-life stuff comes through. It’s a way for them to get a good understanding of the things that we don’t talk about in our appointments with them, but the things that are important and impact on how we manage not only our diabetes, but our every day lives.

Also, they can use them for their patients. If ever a patient says ‘I feel so alone’, I suggested that they direct them to a well-known diabetes blog. There will probably be a post somewhere in the diabetes blogosphere that will address the same issues the PWD are experiencing.

The diabetes social media world does not need to be scary and regarded with suspicion. The role of HCPs is not under threat because PWD are using social media – that’s not what it’s for. It is just the 2.0 version of peer support.

DISCLAIMER

The Can Technology Cure Healthcare’s Future symposium was sponsored by Sanofi. My travel costs were covered by Sanofi, however I did not receive any payment from them. Sanofi had no input into my presentation. Good on them for supporting such an important topic!

I attended the ADS/ADEA conference last week in Sydney just for one day to present at a technology and healthcare symposium (more on that soon).

It was one of those crazy days that started long before the sun rose. I can’t be chipper at 6.30am as my travel companion realised as he greeted me in a very cheery manner only to be met with a steely gaze and pronouncement of ‘I’m yet to have coffee’. It sounded like a threat!

After my presentation, I made the most of a couple of hours at the conference and caught up with as many people as possible. I’d arranged about eight ‘we’ll chat at the conference’ meetings and ended up seeing four people.

I only made it to one session apart from my Symposium and it was a debate.

I love a bit of debating. Those who know me won’t be surprised to know that I was in the debating team when I was at school (Renza nerd fact #3569). But the topic at the conference made me a little uncomfortable and that was before anyone even opened their mouths!

‘It’s our fault if our patients’ HbA1cs are too high’

I don’t like the word ‘fault’. Blaming people for being outside their diabetes targets rarely does anyone any good. As the people living with diabetes, we don’t like to be blamed or told off if we’re not meeting targets, so blaming our HCPs doesn’t make much sense to me either.

Nonetheless, I went along to see what was said.

First up for the affirmative – Cheryl Steele. Now, as far as I’m concerned, Cheryl Steele is wonderful. She was one of the first people I saw present about diabetes when I was first diagnosed with diabetes and she has inspired me ever since. She is a favourite speaker of the T1 Team at DA-Vic, not only because she does a brilliant presentation EVERY SINGLE TIME, but also because of her tell-it-like-it-is manner. And the fact that she is living with type 1 makes her even more awesome! She changed hats a few times yesterday whilst giving her presentation –sometimes speaking as a CDNE and other times as a PWD. And the confusion about anagrams was one of her points.

The affirmative team’s argument was that until HCPs stopped moving the goal posts, provided better tools for management and stopped disagreeing on what they were telling people with diabetes, then yes, they had to consider taking the blame for their patients higher than target BGLs.

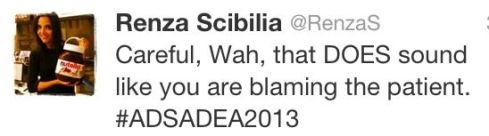

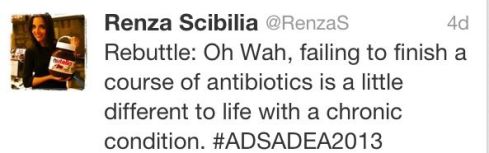

The negative said there was no way that HCPs could be blamed – and were at great pains to point out that they weren’t blaming the PWD. Except there were times that they came pretty damn close – as evidenced by this tweet:

I felt a little uncomfortable at times during the debate. Although it was very tongue in cheek and there was great spirit throughout the session, there were moments that I wondered just how much truth was in the silliness. It is a little like the ‘oh-we’re-just-joking’ comments about patients lying about filling in BGL record books.

I know that by and large the HCPs in the room are there for the PWD (I was sitting next to my endo and I know that’s definitely the case with her), but I do get a little concerned at the lack of understanding about what life with diabetes is all about when the negative team thought that dealing with a life-long chronic health condition is kinda like taking a course of antibiotics.

Was I being a little too sensitive? Possibly. Am I expecting HCPs to get it wrong? Again, possibly. But as a consumer advocate, I am on heightened alert to make sure that there is compassion, understanding and respect being directed towards PWD at all times. I’m not sure that was necessarily the case throughout the debate last week.

Next time, I’d love to see a debate between HCPs and PWD. Now THAT would be worth paying money to see!