Last week I was in Geneva for the 78th World Health Assembly (WHA78). It’s always interesting being at a health event that is not diabetes specific. It means that I get to learn from others working in the broader health space and see how common themes play out in different health conditions.

It’s also useful to see where there are synergies and opportunities to learn from the experiences of other health communities, and my particular focus is always on issues such as language and communications, lived experience and community-led advocacy.

What I was reminded of last week is that is that stigma is not siloed. It permeates across health conditions and is often fuelled by the same problematic assumptions and biases that I am very familiar with in the diabetes landscape.

I eagerly attended a breakfast session titled ‘Better adherence, better control, better health’ presented by the World Heart Federation and sponsored by Servier. I say eagerly, because I was keen to understand just how and why the term ‘adherence’ continues to be the dominant framing when talking about treatment uptake (and medication taking). And I wanted to understand just how this language was acceptable that this was being used so determinately in one health space when it is so unaccepted in others. This was a follow on from the event at the IDF Congress last month and built on the World Heart Foundation’s World Adherence Day.

While the diabetes #LanguageMatters movement is well established, it is by no means the only one pushing back on unhelpful terminology. There has been research into communication and language for a number of health conditions and published guidance statements for other conditions such as HIV, obesity, mental health, and reproductive health, all challenging language that places blame on individuals instead of acknowledging broader systemic barriers.

I want to say from the outset that I believe that the speakers on the panel genuinely care about improving outcomes for people. But words matter as does the meaning behind those words. And when those words are delivered through paternalistic language it sends very contradictory messages. The focus of the event was very much heart conditions, although there was a representative from the IDF on the panel (more about that later). But regardless the health condition, the messaging was stigmatising.

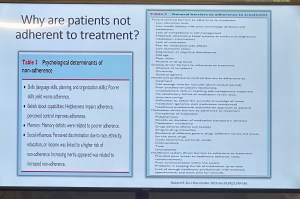

The barriers to people following treatment plans and taking medications as prescribed were clearly outlined by the speakers – and they are not insignificant. In fact, each speaker took time to highlight these barriers and emphasise how substantial they are. I’m wary to share any of the slides because honestly, the language is so problematic, but I am going to share this one because it shows that the speakers were very aware and transparent about the myriad reasons that someone may not be able to start, continue with or consistently follow a treatment plan.

You’ll see that all the usual suspects are there: unaffordable pricing, patchy supply chains, unpleasant side effects, lack of culturally relevant options, varying levels of health literacy and limited engagement from healthcare professionals because working under conditions don’t allow the time they need.

And yet, despite the acknowledgement there is still an air of finger pointing and blaming that accompanies the messaging. This makes absolutely no sense to me. How is it possible to consider personal responsibility as a key reason for lack of engagement with treatment when the reasons are often way beyond the control of the individual?

The question should not be: Why are people not taking their medications? Especially as in so many situations medications are too expensive, not available, too complicated to manage, require unreasonable or inflexible time to take the meds, or come with side effects that significant impact quality of life. Being told to ‘push through’ those side effects without support or alternatives isn’t a solution. It is dismissive and is not in any way person-centred care.

The questions that should be asked are: How do we make meds more affordable, easier to take, and accessible? What are the opportunities to co-design treatment and medication plans with the people who are going to be following them? How do we remove the systemic barriers that make following these plans out of reach?

One of the slides presented showed the percentage people with different chronic conditions not following treatment. Have a look:

My initial thought was not ‘Look at those naughty people not doing what they’re told’. It was this: if 90% of people with a specific condition are not following the prescribed treatment plan, I would suggest – in fact, I did suggest when I took the microphone – the problem is not with the people.

It is with the treatment. Of course it is with the treatment.

The problem with the language of adherence is that it frames outcomes through the lens of personal responsibility. It absolves policy makers of any duty to act and address the structural, economic and systemic barriers that prevent people from accessing and maintaining treatment. Why would they intervene and develop policy if the issue is seen as people being lazy or not committing to their health?

And it means the healthcare professionals are let off the hook. It assumes they are the holders of all knowledge, the giver of treatment and medications, and the person in front of them is there do what they are told.

There is no room in that model for questions, preferences, or complexity. There is no room for lived experience. There are no opportunities for co-design, meaningful engagement or developing plans that are likely to result in better outcomes.

When the room was opened up to questions, I raised these concerns, and the response from the emcee was somewhat dismissive. In fact, she tried to shut me down before I had a chance to make my (short) comment and ask a question. I’ve been in this game long enough to know when to push through, so I did. I also don’t take kindly to anyone shutting down someone with lived experience, especially in a session where our perspective was seriously lacking. Her response was to suggest that diabetes is different. I suggest (actually, I know) she is wrong.

And I will also add: while there was a person with lived experience on the panel, they were given two questions and had minimal space to contribute beyond that. I understand that there were delays that meant they arrived just in time for their session, but they were not included in the list of speakers on the flyer for the event while all the health professionals and those with organisation affiliation were. There comments were at the very end of the session, and I was reminded of this piece I wrote back in 2016 where health blogger and activist Britt Johnson was expected to feel grateful that the emcee, who had ignored her throughout a panel discussion, gave her the last five minutes to contribute.

Collectively this all points to a bigger issue, and we should name that for what it is: tokenism.

I didn’t point this out at the time, but here is a free tip for all health event organisers: getting someone to emcee who is a journalist or on-air reporter does not necessarily a good emcee make. Because when you have someone with a superficial understanding of the nuance and complexity involved in living with a chronic health condition, or understand the power dynamics and sensitivities required when facilitating a conversation about long-term health conditions, you wind up with a presenter who may be able to introduce speakers, but you miss out on meaningful and empathetic framing of the situation. There are people with lived experience who are excellent emcees and moderators, and bring that authenticity to the role. Use them. (Or get someone like Femi Oke who moderated the Helmsley + Access to Medicine Foundation session later in the day. She had obviously done her homework and was absolutely brilliant.)

I know that there has been a lot of attention to language in the diabetes space. But we are not alone. In fact, so much of my understanding has come from the work done by those in the HIV/AIDS community who led the way for language reform. There are also language movements in cancer care, obesity, mental health and more. And even if there are not official guidelines, it takes nothing to listen to community voices to understand how words and communication impact us.

So where to from here? In my comment to the panel, I urged the World Heart Foundation to reconsider the name of their campaign. Rather than framing their activities around adherence, I encouraged them to look for ways to support engagement and work with communities to find a balance in their communications. I asked that they continue to focus on naming the barriers that were outlined in the presentations, and shift from ‘How to we get people to follow?’ to ‘How do we work with people to understand what it is that they can and want to follow?’.

Finally, it was great to see International Diabetes Federation VP Jackie Malouf on the program on the panel. She was there to represent the IDF, but also brought loved experience as the mother of a child with diabetes. The IDF had endorsed World Adherence Day and perhaps had seen some of the public backlash about the campaign and the IDF’s support. Jackie eloquently made the point about how the use of the word was problematic and reinforced stigma and exclusion, and that there needs to be better engagement with the community before continuing with the initiative.

4 comments

Comments feed for this article

May 28, 2025 at 5:26 pm

Tim Brown

Excellent blog on an important topic for all of those who live with health challenges

LikeLike

May 28, 2025 at 6:13 pm

Rick Phillips

The graphic you shared is compelling. I could not read the top middle condition, but I do not think it is arthritis. Whatever it is, one has to look at the reasons behind not achieving this 100% goal. Cost is number one for many condiitons. But that is not an overwhelming issue like with heart failure or coronary artery disease. The number one issue in those cases is that the medications are rudimentary at best. You cannot separate success or ‘compliance’ from the fact that unless the medications work, people will not use them. Why should they?

I am a co-author on a paper that will be presented at EULAR this year. It is about preferences for arthritis medication delivery methods. Turns out people prefer pills over injections. Yet most of the inflammatory arthritis medications are delivered via injection. This method reduces medication adherence substantially. So here is the question: what is needed? Is it turning more medications into pill delivery? That would help. But in the short run, maybe injection training like we people with diabetes undergo when first diagnosed.,

Turning advanced biologics into pills is not possible. So we can complain about “adherence,” or we can do something about it. The first is acknowledging that we can coach people into using injections if we give them support and training. Yet, it is so much easier to sit back and complain. After all, complaining is much easier.

LikeLike

May 29, 2025 at 2:48 pm

Colleen Goos

I think, too that professionals, as well as family, need to take a step back and see that even when two people have the same condition, they experience it very differently. I know *my* T1D, Arthritis, spinal condition, etc. I don’t know anyone else’s. I get so angry when someone tells me “well this person who also has T1D drives and lives a perfectly normal life.” I’m sorry but I don’t think there’s anything normal about diabetes and its treatment, but that’s beside the point.

There are multiple reasons besides diabetes that I don’t drive, i.e. as a Little Person, we would have to have 2 cars, with one that could be adjusted specifically for my stature and spine. This is something we can’t afford.

I also experienced my daughter being hit by a car and was waved across the road. Being a teen she trusted an adult driver waving her across The only reason she survived a 50MPH hit was that the driver was not impaired. It was truly accidental and he attempted to avoid her. My blood sugar is volatile even with CGM and pump therapy because of my *hypersensitivity* to dosing insulin in either direction so I have very rapid highs and lows. Since I saw what a car can do to a human body, I am not comfortable with driving and trying to manage diabetes, arthritis pain, and spinal pain at the same time.

C-PTSD from childhood traumas led to problems with my diabetes and whole outlook on life in general, so “adherence” is a word that would make me ill at ease with someone, especially a doctor.

LikeLike

May 30, 2025 at 6:58 pm

rainley

Hi Renza,

How are you and your family going?

First of all, I want to say I’m so sorry to hear about the way the emcee treated you and the person with lived experience on the panel. It’s so frustrating to know this keeps happening so good on you for continuing to push back against it.

I also want to thank you for all your blogs and this one in particular. I’m currently writing some content on common psoriasis comorbidities and am up to the section on metabolic disorders. I thought I’d been super careful about avoiding “blaming” language when summarising common causes of these conditions. After all, I live with steroid-induced type 2 diabetes, so I should know better. However, I hadn’t thought to include broader barriers to care as contributing factors. Thanks to you, I’ve fixed that.

On a separate note, I must have signed up for your emails twice as I get two each time. Can you fix that when you get a chance? Thanks.

As always, let me know if I can help you in any way.

Regards,

Rosemary Ainley

LikeLike