In most cases, the answer to the question in the title of today’s blog post would be ‘no’. At best there might be a nod to some sort of involvement of people with lived experience. Most likely, there would have been some avenue for ‘feedback’ and that would be touted as ‘consultation’ and ‘engagement’. Spoiler alert: It’s neither.

The impact of co-design when done well can’t be underestimated. Have a look at D-Coded Diabetes for one example. This brilliant resource brings together PWD, researchers and clinicians to improve access to and understanding of diabetes research. The development of the international consensus statement to bring an end to diabetes stigma is another example – from its conception right through to the launch event. And this article published in BMJ just last week involved researchers, clinicians and people with lived experience to talk about the importance of uninterrupted access to insulin during humanitarian and environmental crises and was supported by the Patient Editor at BMJ.

I so often hear that initiatives are co-designed, but a look under the hood suggests otherwise. The same goes for when we are told that there has been engagement or consultation. The three terms get bandied around a lot when the truth is that there is so very little involvement at all with the very people who the work is for or about. (More for and about, rather than with and by.)

I grow increasingly frustrated at claims that PWD have been involved, because it’s simply not true. But even more worrying is how these claims are used to throw people with diabetes under the bus. Let me explain.

Not too long ago, a diabetes campaign was set free in the wild. It was not received all that well by many people in the community. I remember being alerted to it with messages from a number of advocates, and a quick look on Twitter and on other socials was all it took to see that many in the community were not too impressed, and they had made their feelings known.

I reached out to someone about the campaign and was told that it was ‘extensively tested with people with diabetes’. That response has stuck with me. Pointing to testing with PWD is, in effect, throwing PWD under the bus. The subtext of that is ‘Don’t blame us. We showed it to PWD.’

The plot thickened when I reached out to a couple of people who had allegedly seen the campaign only to be told ‘I saw it on Facebook this morning for the first time’. While that is troubling, it’s actually not the point. The point is that there is a feeling that ‘testing’ a campaign (or anything else) means that if it doesn’t land well, it’s the fault of the PWD who (probably cursorily) glanced at it. Whoever designed and launched it simply washes their hands of any responsibility.

I didn’t respond to the ‘extensively tested’ defence. But if I had this is what I would have liked to say: Just how much involvement did those people who ‘extensively tested’ the campaign have? Were they involved in the development or were they only brought in after the whole thing had conceived, story-boarded, filmed, been through post-production and was ready to launch? Were any of their recommendations, concerns, ideas taken on board? How and where? How many times did they see the campaign materials before launch date? Are they recognised or acknowledged anywhere as co-designers? Were they paid for their time and expertise? Getting answers to these types of questions forms a pretty good picture of how much engagement truly happened.

It shouldn’t need to be said but testing something – extensively or otherwise is no co-design. It’s not engagement. It’s not consultation. It’s an afterthought.

So is asking for ‘feedback’. By the time there is something to feed back on, too much work without the community has already transpired. My response to being asked to provide feedback these days is ‘No’, followed by an explanation that I am always happy to feed-in when things are being developed, but I refuse to simply feedback to satisfy some token window dressing engagement attempt.

Also, going to the right people for the right project is also critical. This remains one of the reasons that I feel challenged by the idea of community advisory groups. How is it possible to engage with the same people, regardless of the project. Most advisory groups would have a couple of people with each type of diabetes, a parent or two with a child with diabetes, someone from a rural setting. But really, are those people with T1D the best people to engage if the work that is being done is about older adults with T2D in aged care facilities? Or if the work is to do with gestational diabetes education, are parents of primary school-aged kids the best people to provide lived experience expertise?

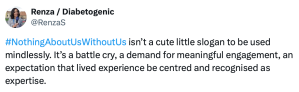

We have a hashtag in lived experience communities that is a rallying cry. I use it constantly because I love it, but I also often use it because I am frustrated. And that frustration led to this tweet a few weeks ago:

Saying #NothingAboutUsWithoutUs is how our lived experience community advocates for true community involvement and meaningfully change the status quo. We are the ‘us’ in the hashtag. The #dedoc° team uses it a lot because it forms the basis of so much of our organisation’s work. It is not okay for others to appropriate the term, seemingly hoping that it will lend them some credibility with PWD. It won’t.

There are stellar examples of how co-design works and can be truly branded with the #NothingAboutUsWithoutUs hashtag. The work that has been underway by a community group, to progress equity in access AID is one current example. The meeting in Florence that kicked this work off didn’t actually involve community. And yet, from there, a couple of endos in the meeting reached out to the community to put together a plan to make change that has a seat for everyone at the table. (And the fact that over 4,400 community members have signed this petition suggests that it resonates!)

It can be done! If you need some ideas for where to start, we really can’t make it any easier. Here are some guidelines that were launched earlier this year Jazz Sethi and I collated. It’s a really useful guide for how to kick things off. I think it’s time that we start asking questions when there is a claim of engagement. Let the burden of proof on that lay with anyone making the assertion. Because it’s easy to see when it’s done well. And even easier to see when it’s not.

1 comment

Comments feed for this article

May 26, 2024 at 12:11 pm

Rick Phillips

Having had my good name used to assuage some need to say they involved patients, I get where you are coming from. I do not mind being asked to give my thoughts. but being told what i need to think and then deciding that is what i did somehow bothers me a lot.

Actually if you just want me to agree with you, send me $500, I will stay home and we will both come out way ahead.

LikeLike